An Excerpt from The Crusade

by Jon Jackson

(Used by permission from the Old Huntsville Magazine.)

NOTE: This story was edited from a longer article to highlight events that occurred in Huntsville.

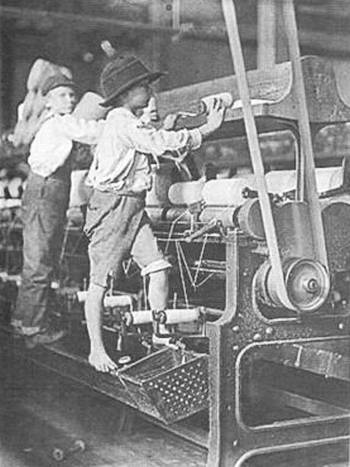

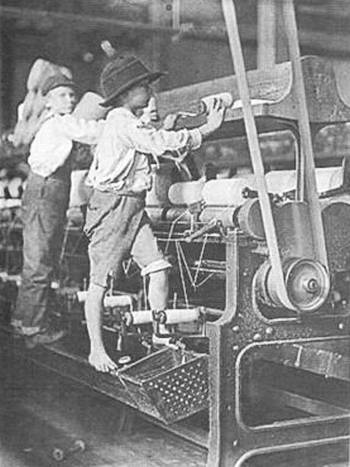

They say pictures don't lie. Lewis Hine, the crusading social photographer of the early 20th century, built his career on this assumption. Around the nation and in Huntsville he took pictures of children working in the fields, mines, and factories of a nation caught in the gears of industrialization. These children look at you from the depths of time as if to say, "I was here, remember me." In black and white, in tattered clothes, in a childhood cut short by work in the Huntsville cotton mills, they lived lives not forgotten. At the dawn of the twentieth century Lewis Hine waged his crusade to take children out of the workplace and give them a childhood. In the end, he failed. But it was a glorious failure.

Lewis Hine was born in 1874 in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. In 1907, with a growing family to support, Hine began working for the National Child Labor Committee. Over the next ten years he logged hundreds of thousands of miles crisscrossing the nation, photographing children working in the industries of America. Much of his work was done in Huntsville where he captured the images of the young children working in the mills. At Dallas, Lowe, Merrimack, and Lincoln he saw children going in and out of the mills. Many of them were underage, some as young as seven, their parents having lied on the affidavits they were required to sign attesting to the age of the child. Often the family needed the money and not having any education themselves, they did not want their children "wasting" their time going to school.

They say pictures don't lie. Lewis Hine, the crusading social photographer of the early 20th century, built his career on this assumption. Around the nation and in Huntsville he took pictures of children working in the fields, mines, and factories of a nation caught in the gears of industrialization. These children look at you from the depths of time as if to say, "I was here, remember me." In black and white, in tattered clothes, in a childhood cut short by work in the Huntsville cotton mills, they lived lives not forgotten. At the dawn of the twentieth century Lewis Hine waged his crusade to take children out of the workplace and give them a childhood. In the end, he failed. But it was a glorious failure.

Lewis Hine was born in 1874 in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. In 1907, with a growing family to support, Hine began working for the National Child Labor Committee. Over the next ten years he logged hundreds of thousands of miles crisscrossing the nation, photographing children working in the industries of America. Much of his work was done in Huntsville where he captured the images of the young children working in the mills. At Dallas, Lowe, Merrimack, and Lincoln he saw children going in and out of the mills. Many of them were underage, some as young as seven, their parents having lied on the affidavits they were required to sign attesting to the age of the child. Often the family needed the money and not having any education themselves, they did not want their children "wasting" their time going to school.

In the Huntsville cotton mills children were often hired as "doffers," "spinners," and "sweepers." Doffers went around the mill replacing the whirling bobbins as they filled with thread. Spinners kept an eye on the bobbins and when a thread broke they tied the ends together. Sweepers kept the floors clean so the other workers could do their jobs more efficiently. The mill owners valued the small workers whose deft fingers meant they could do the work quickly and thus maximize the money the mill owners spent. And, because they were children, the owners did not have to pay them as much as an adult.

At the time machinery often lacked even basic safety features. Moving parts were often exposed and it was easy to get a limb caught and mangled. Once, while Hine was at a factory he reported, "A twelve year old doffer boy fell into a spinning machine and the unprotected gearing tore out two of his fingers. "We don't have any accidents in this mill," the overseer told me. "Once in a while a finger is mashed or a foot, but it doesn't amount to anything."

At first Hine managed to gain access to the mills themselves, taking pictures of children so small they had to stand on the spinning machines to do their work. He would tell the supervisors he wanted to photograph the mills themselves. Fumbling around with the camera and equipment he would deliberately waste time until the supervisor would grow bored and wander off. Hine then set about on his real task of photographing the children. Later the pictures would end up in newspapers and in displays the National Child Labor Committee set up around the country to raise awareness of child labor. When the mill owners caught on they barred him from the mills and instructed the supervisors to run him off when they caught him around. Hine then began hanging around outside the mills, taking pictures of the children coming and going to work.

The cotton mills began to put pressure on Hine, hoping to run him out of town. Other Huntsville businesses, beholden to the cotton mills, refused to sell anything to him. He was refused admittance to businesses and had to order his film from out of town. At one point he was forced to sleep in his car when a local hotel refused to rent him a room.

But taking pictures was only half the battle. It still remained to convince the nation that these invisible children who made the conveniences that they brought were people. Hine had to give his vision to others. On breaks from his schedule of shooting at the factories he would go around the nation lecturing about what he saw in the factories, mines, and streets of the nation where children labored. He told of the brutal 13-hour days of backbreaking labor to groups of affluent, middle class whites. He told how children, too young to protest, were enslaved by corporate greed. In one instance he came to Huntsville on his lecture tour, he had to change the captions on some of the pictures to avoid being run out of town.

The wealthy cotton mill owners began a campaign to discredit Hine and his photographs. Powerful lobbyists in Washington labeled him a Communist and assertions were made that his photographs were staged. One lobbyist went so far as to say that the children portrayed in the pictures were actually dwarfs.

Despite the criticism leveled at him Hine refused to defend himself, choosing instead to let the photographs speak for themselves. President Wilson, after viewing the photographs, was said to have been "shocked to his inner core." The stark black and while photos of young children enslaved to corporate greed created a national controversy and people began pressing for reform.

In 1916 and again in 1918 Congress passed child labor reform laws but the Supreme Court struck them down. In 1924 Congress attempted to pass a Constitutional Amendment that would authorize a national child labor law. At each of the hearings Hine's photographs of children working in the Huntsville cotton mills were exhibited.

Groups opposed to any increase in federal law in areas relating to children lobbied against the amendment and within ten years the measure died. Only during the Great Depression of the 1930s did child labor finally begin dying. But not because of activism or laws: In this period of high unemployment men competed even for the lowest paying jobs formerly held by children. At the same time labor unions began to agitate for change. But the most powerful reason for change was the growing need by industry for more skilled workers. School became, not an option, but a necessity to get a job. It was not until 1938, when President Roosevelt signed the Fair Labor Standards Act, that severe restrictions were placed on child labor. Amended in 1949 the law finally put teeth in the regulation of child labor. Yet even today, in dark out-of-the-way corners, child labor continues.

The genius of Lewis Hine wasn't in the composition of his pictures or in his decision to use the camera. The genius of Lewis Hine was his ability to see the invisible person and show that person to us, very clearly.

His pictures helped change a nation but in Huntsville, home of the cotton mills he photographed, he had been conveniently forgotten…until now.

They say pictures don't lie. Lewis Hine, the crusading social photographer of the early 20th century, built his career on this assumption. Around the nation and in Huntsville he took pictures of children working in the fields, mines, and factories of a nation caught in the gears of industrialization. These children look at you from the depths of time as if to say, "I was here, remember me." In black and white, in tattered clothes, in a childhood cut short by work in the Huntsville cotton mills, they lived lives not forgotten. At the dawn of the twentieth century Lewis Hine waged his crusade to take children out of the workplace and give them a childhood. In the end, he failed. But it was a glorious failure.

Lewis Hine was born in 1874 in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. In 1907, with a growing family to support, Hine began working for the National Child Labor Committee. Over the next ten years he logged hundreds of thousands of miles crisscrossing the nation, photographing children working in the industries of America. Much of his work was done in Huntsville where he captured the images of the young children working in the mills. At Dallas, Lowe, Merrimack, and Lincoln he saw children going in and out of the mills. Many of them were underage, some as young as seven, their parents having lied on the affidavits they were required to sign attesting to the age of the child. Often the family needed the money and not having any education themselves, they did not want their children "wasting" their time going to school.

They say pictures don't lie. Lewis Hine, the crusading social photographer of the early 20th century, built his career on this assumption. Around the nation and in Huntsville he took pictures of children working in the fields, mines, and factories of a nation caught in the gears of industrialization. These children look at you from the depths of time as if to say, "I was here, remember me." In black and white, in tattered clothes, in a childhood cut short by work in the Huntsville cotton mills, they lived lives not forgotten. At the dawn of the twentieth century Lewis Hine waged his crusade to take children out of the workplace and give them a childhood. In the end, he failed. But it was a glorious failure.

Lewis Hine was born in 1874 in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. In 1907, with a growing family to support, Hine began working for the National Child Labor Committee. Over the next ten years he logged hundreds of thousands of miles crisscrossing the nation, photographing children working in the industries of America. Much of his work was done in Huntsville where he captured the images of the young children working in the mills. At Dallas, Lowe, Merrimack, and Lincoln he saw children going in and out of the mills. Many of them were underage, some as young as seven, their parents having lied on the affidavits they were required to sign attesting to the age of the child. Often the family needed the money and not having any education themselves, they did not want their children "wasting" their time going to school.