From The Historic Huntsville Quarterly of Local Architecture and Preservation, Volume XXV, Nos. 3&4, Fall/Winter 1999, pgs. 33-42.

Introduction"The search continues, as it always will, for the best way to create a physical environment conducive to learning," Harvie P. Jones wrote in his essay on the architecture of Huntsville's schools. His point is that school buildings, like the schools housed in them, constantly change in response to the changing educational climate.

Demographic changes, shifts in educational responsibility between the private and public sectors, shifts between centralized and neighborhood schools, and changes in educational theory have affected the design of our schools as much as the hard realities of budgets and materials. Harvie's essay, and the accompanying photographs, describe the changing appearance—and the reasons underlying those changes—of our schools. Written in 1986 (Vol. XII, Nos. 3 & 4, Spring/Summer, 1986), the essay provides a means of describing and evaluating schools that have been built since then.

In view of the myriad challenges to today's schools, Harvie's underlying thesis is of particular relevance: New educational situations, he suggests, have always required, and usually prompted, new architectural remedies. His hope is expressed in the essay's last sentence: "Future architects, school boards, faculties/staffs will continue efforts to make the buildings work as well as possible as one element in aiding learning."

ArticlePrior to 1882, Huntsville's school buildings were all private. In the early 19th century, it was widely felt that "taxing one man's property to educate another man's child" was not proper, according to Lawrence A. Gremlin's Transformation of the School. Others, such as Horace Mann and Catherine Beecher, viewed education as a public enterprise (Andrew Guilliford, America's Country Schools). By 1873, efforts were under way in Huntsville to establish a public school system. In 1875, the system was formally established and the first public school building was completed in 1882.

This first public school building was located on a site that has been used continuously for educational facilities since the first quarter of the 19th century—the block bounded by East Clinton Avenue, White Street, Calhoun Street, and East Holmes Avenue. This site has successively accommodated Green Academy, a private school of considerable reputation, built in 1822 and burned in the Civil War; the first public school building, built in 1882; a large twelve-grade public school built about 1902; and East Clinton Elementary School, built in 1938.

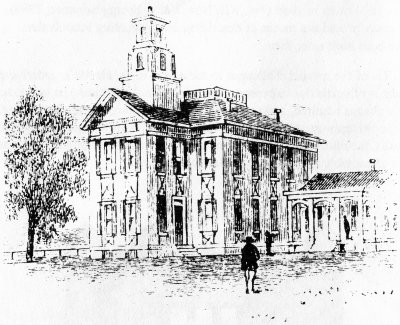

The 1882 building, based on an extant sketch and description, contained two large classrooms, two small classrooms, and a chapel [also used as an assembly room] (see Fig. 1). The cubically-proportioned two-story building was a curious mixture of stylistic influences: Italianate form and proportions, a Colonial Revival belfry reminiscent of a New England 18th century church (minus the spire), and Victorian stick-style spandrel decorations between the upper and lower windows. The windows were tall and closely spaced in the Italianate manner to provide plenty of light and ventilation for the interior. What appear to be metal stove flues penetrate the roof at each room location. The building bears a strong family-resemblance to several of the 1880-1900 period schools shown in Andrew Guilliford's America's Country Schools.

In 1882, the school census indicates only 133 of 800 Huntsville students attended this public school. Apparently there were several private schools in operation at this time.

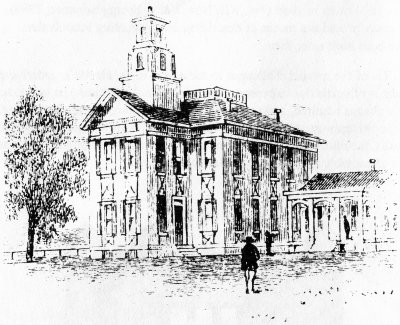

An indication of how rapidly the public school system was growing in the late 19th century was that this first small school building was demolished in just twenty short years to make way for a much larger building in about 1902 (see Fig.2). A photograph appears to indicate that this 1902 building contained at least twelve classrooms for the twelve grades it housed, and had an auditorium at the center. This was a two-story red-brick Romanesque-Revival influenced design, with rounded-arch openings at the belfry tower and entry, and castellated parapets at the tower top and end towers. A tall pyramidal spire topped the castellated belfry tower.

A new and modem feature was the grouping of six windows directly together to form large continuous window-walls at the class-rooms, maximizing light and ventilation. Many classrooms had windows on two walls, further improving lighting and ventilation. The solid, monumental air of the building served to communicate the perceived importance of public education to the community and to visitors.

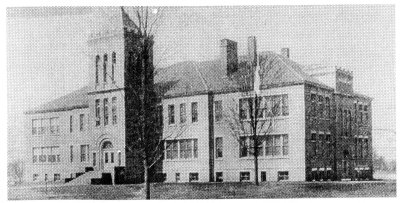

By 1916, public education in Huntsville had grown to the point that a separate high school was needed. It was built on West Clinton Avenue two blocks west of Jefferson Street (see Fig.3). This school was a handsome Classical Revival brick two-story-plus-basement structure with a Tuscan-columned portico, heavy roof-cornice, roof parapets, and a rusticated wall-base. It contained at least fifteen classrooms, plus more rooms in the basement, and a good-sized auditorium with a sloped floor and proscenium-arch stage. Unlike the previous schools, this high school had a central heating system consisting of a boiler and radiators served by distribution pipes.

This 1916 building has a fond place in the hearts of many Huntsvillians who never attended school there. From about 1962 until 1974, it served as the temporary Civic Arts Center and as offices for the recently formed Arts Council. The building saw hundreds of plays, art exhibits, dance and painting classes, rehearsals, and arts activities of every description. Huntsville's greatest period of growth and maturity in the arts was accommodated in this building.

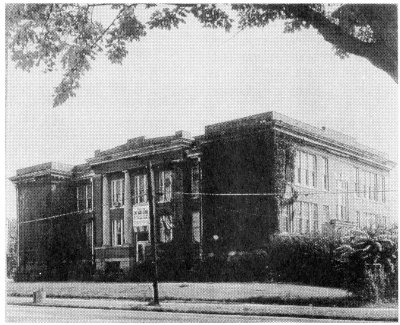

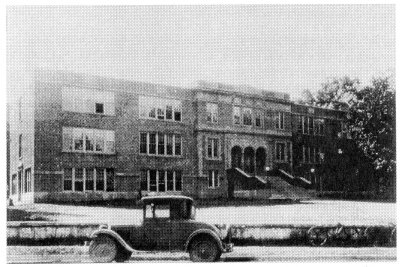

Only ten years later, it was necessary to expand Huntsville's high school capacity. By this time, the private schools were a minor factor in education, and the town was growing rapidly in the 1920s boom. Thus in 1927, a new Huntsville High School was built near the comer of Randolph Avenue and White Street (see Fig.4). This was a full three-story building containing about eighteen classrooms. The stylistic influence, like that of the 1916 high school, was the Renaissance. A trio of rounded arches and Tuscan colonettes graced the raised entry, atop a flight of monumental steps. On the parapet above the entry was a double baroque scroll and urn ornament, later lost to lightning. The ornamentation at the entry, which appears to be cut limestone, is in fact "cast stone," or cement and sand cast into elaborate moulds to resemble cut limestone. The classroom windows were wood, divided-light, double-hung sashes in banks of five. These windows in the 1960s were replaced with inappropriate aluminum ranch-style windows, which the school board presently hopes to remove in a restoration of this handsome building. The various wings were also added in the 1960s.

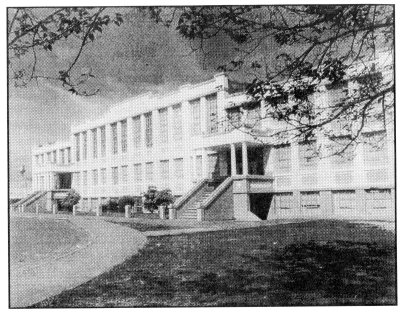

There was rapid growth in cotton-goods manufacturing in Huntsville from the late 19th century through the 1920s. The various mill villages built just outside the city limits included not only the mills, but also housing, commercial buildings, and schools. Rison School (1920), Lincoln School (1929), and Joe Bradley School were three of these. Joe Bradley is gone, Rison will be demolished shortly for I-565, but Lincoln is still in excellent condition and is being used as Lincoln Elementary School (see Fig.5). The monolithic reinforced concrete structure is so sound that (in the words of the School Maintenance Department) "it could probably be rolled end-over-end without hurting it much." Lincoln School's stylistic category could be termed stripped Renaissance Classical. It has the pilasters, stepped parapets, high central block flanked by lower wings, Tuscan colonettes, and cove-comer spandrels that can be seen in more elaborate buildings of Renaissance Revival design.

Rison School (1920) reflects the Spanish Colonial Revival in a simplified form. It is low and rambling, stucco with brick archways, has a steep pitched roof, and is U-shaped around a central courtyard. [Editor's note: Rison School has been demolished. See Historic Huntsville Quarterly Vol.XXIV, No.3, Fall T998, page 40 for picture of school.]

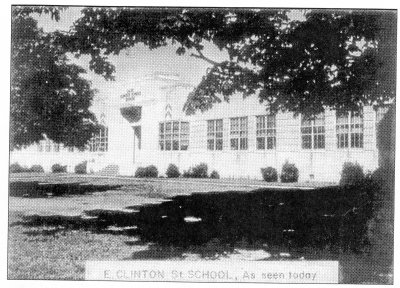

By 1938, the 1902 school on East Clinton Avenue (described earlier) had been demolished and replaced with the present East Clinton Elementary School (see Fig.6, page 39). Its style is Art Deco, one of the first of the so-called modern 20th century styles that made a conscious effort to avoid borrowing from ancient styles. This style is exemplified in the chevrons, flutes, and circles at the entry. The light-colored one-story brick building is in an E shape (but not because it is E. Clinton School) with the assembly room in the center leg of the E. Thus, this 1938 building is the fourth on the Clinton Street site, which has been used only for educational buildings since the Green Academy first occupied the site in 1822, a period of 164 years.

Blossomwood and Westlawn Elementary Schools (1956) were the first Huntsville schools influenced by the modem International Style, wherein walls are treated as rectangular panels and modulation of surfaces is minimized. Variety of form is achieved by pushing and pulling the panels (walls) in and out, up and down. Planes rather than masses are emphasized. The window walls at Blossomwood consist of curtain walls of prefabricated window-plus-spandrel units bolted or welded into place to entirely fill the wall opening (see Fig.7). Inside lighting is balanced by using skylights in the corridors and clerestories to borrow daylight from the corridors.

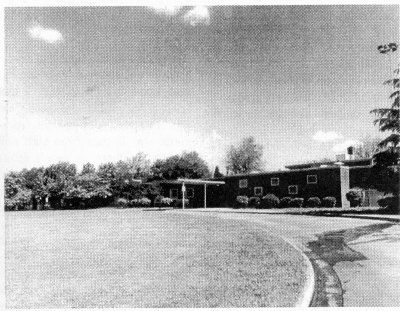

The space-boom years of 1954-1968 saw the construction of an amazing thirty-plus schools and school additions. This is about three-fourths of all school buildings existing in the City of Huntsville school system. In the late fifties, the honest boast was made that Huntsville was building schools at the average rate of "one classroom per week" to meet the huge influx of students. This large number of new schools, up until 1966, shared a number of characteristics. They were nearly all one-story, and as a consequence, rambled over their sites in a loose arrangement of low, flat-roofed wings. Many used curtain walls and all had a full wall of windows at one side of each classroom. Many had skylights in the classrooms and other spaces. An awkward hybrid word - cafetoriums - was devised by some planner to describe the combination cafeteria-auditoriums used in the smaller schools. These cafetoriums usually were considerably taller than the rest of the building and sometimes had irregular-profile roofs, as well, to give a visual accent to the sprawling building.

In design, the 1954-66 buildings were deliberately non-monumental, in contrast to the earlier buildings. They were strongly influenced by the International Style and also by the research and design of such nationally-known architects as Caudill, Rowlett, Scott, and Perkins and Will. An influential book of 1958 was Schoolhouse, edited by Walter McQuade and published by Simon and Schuster. This book went far beyond style and attempted to analyze the human factors in the educational process with the hoped-for result of more humane educational spaces. These buildings did achieve an informality, but humaneness is more than mere informality. The search continues, as it always will, for the best way to create a physical environment conducive to learning.

In the mid-1960s, an organization, funded by foundation grants, called Educational Facilities Laboratories (EFL) had a strong and almost revolutionary impact on school design and methods of teaching here aiid nationally. The concept of team teaching was in the experimental stages, and EFL devised ways of reshaping the typical school of straight rows and self-contained thirty-student, one-teacher classrooms to work with the idea of team teaching. EFL grouped the classrooms so that a team of three to six teachers could work with varying groups of students in a large flexible space that sometimes could be subdivided into smaller spaces. A teachers' planning room was adjacent so that teachers could indeed plan as a team. Windows, with the common advent of air conditioning and fluorescent lighting, were reduced or eliminated since uncontrolled daylight interfered with audio- visual aids such as films, television, and overhead projectors. One of the most visually startling aspects of this design revolution was that the boxy, planar International Style buildings of the 1950's were replaced by schools of many shapes.

Huntsville's first elementary school of this type was McDonnell Elementary (1967), whose pods of classrooms were a cluster of five hexagons, each accommodating 120 students, four teachers and an assistant, restrooms, and a teachers' planning room. Butler High School (1967), Chaffee (1969), Grissom (1969), and Ed White (1969) were similarly more free in geometric form than the pre-1967 schools. Huntsville's first school that was a result of an extensive programming study was J.O. Johnson High School (1972). An educational consultant was engaged. A large study committee was formed from staff' and faculty members. A year's effort resulted in a highly detailed program whose philosophy was to encourage initiative in students, then to aid the student in highly flexible ways in achieving his goals. While pods and team-teaching were involved, it was in a more flexible arrangement than in the latter 1960s plans. It contained both pods and individual classrooms where they were appropriate (see Fig.8).

The best that any school building can do is to interfere as little as possible with the learning process. Buildings cannot educate anyone—they can only make the process a little more pleasant. Future architects, school boards, faculties/staffs will continue efforts to make the buildings work as well as possible as one element in aiding learning.