By Ben Phelan

This article from the Antiques Roadshow has been archived here to ensure it stays available.

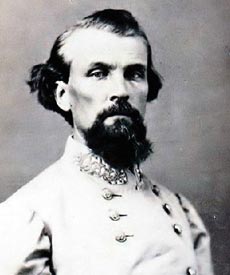

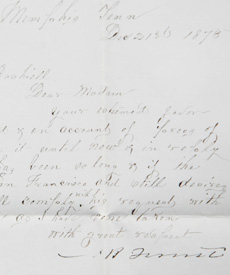

In June 2008 a ROADSHOW guest named Ellen Dashiell Lentz and appraiser Christopher Mitchell discussed a collection of Confederate memorabilia that had been passed down to Ellen through three generations of her family. The items included several veterans ribbons, a photograph of Ellen's great-grandfather, George Dashiell, and an 1875 letter to her great-grandmother from Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, one of the most famous — and controversial — figures to emerge from the entire American Civil War.

The reputation of General Forrest, under whom Ellen's great-grandfather served during the latter half of the war, has come to be defined by two infamous, yet brief, chapters in his life: his controversial assault on the Union-held Fort Pillow in 1864; and his post-war involvement with the first incarnation of the Ku Klux Klan. So closely is Forrest's name associated with the Klan, in fact, that he is sometimes incorrectly referred to as its founder. If not for these two black marks on his reputation, the ribbons and regalia appraised by Christopher Mitchell at around $10,000 would undoubtedly be quite a bit more valuable. Though totally uneducated, Forrest was a demonically gifted military commander and tactician, a legend in his own time. He was the only man on either side to rise from the rank of private to that of general during the four-year conflict. Robert E. Lee and William Tecumseh Sherman called him the most remarkable man, and finest soldier, produced by the war.

Forrest and his 10 siblings grew up well beyond the edge of the civilized world, in a two-room cabin in the middle of Tennessee. His father was a blacksmith and subsistence farmer, his mother a virtual giantess at six feet. Forrest survived the typhoid that killed half his siblings, including his twin, and at 21 left home to become a planter and slave trader in Memphis. He soon became one of the wealthiest men in the South. In 1861, when he was 40 years old, Tennessee seceded from the Union. The survival of the South, and of Forrest's livelihood, were suddenly thrown into doubt, and Forrest joined the Confederate Army.

His violent temper was perfected in the theater of war: he immediately distinguished himself as a natural military genius. Sherman confessed to being perpetually flummoxed by Forrest's feral cunning and exhausted by his energy. In his first engagement, in Kentucky, Forrest defeated a Union force twice the size of his own. In subsequent battles, he took on and defeated, time and again, larger, better-equipped, and more thoroughly trained forces, often by dint of subterfuge and deceit — more than once he tricked Union commanders into surrendering to his smaller force — but just as often by ferocity and shrewdness. He fought alongside his troops, and by the end of the war had personally killed 30 enemy soldiers. His own horses fared only a little better. He had 29 shot from underneath him, sometimes one within minutes of its ill-fated successor. He was wounded four times, two bullets coming to rest near his spine.

In the spring of 1864, low on provisions, Forrest attacked and captured Fort Pillow, a garrison north of Memphis. The incident became perhaps the most controversial military action in the Civil War, as Forrest had at his command more than twice as many soldiers as were occupying the fort, about half of whom were recently freed slaves. Surrounded and outnumbered, the Union forces declined to surrender, and, typically, Forrest was ruthless. His men overran Fort Pillow, taking few prisoners. The Union called the battle a massacre. Forrest would later appear before Congress to defend himself against charges of war crimes, and though he was found not guilty, he was known to many, for the rest of his life, as the Butcher of Fort Pillow.

After the war, Forrest returned to a devastated Tennessee and publicly advocated for peaceful submission to the victorious Union. But he was not the beneficiary of a sudden racial enlightenment, nor did he submit entirely to the new world order, one characterized by the societal tumult of Reconstruction and the removal of the Southern economy's cornerstone. Perhaps blacks were no longer slaves, but, Forrest believed, they had to remain the South's docile workforce, for their own good as well as his. "I am not an enemy of the negro," Forrest said. "We want him here among us; he is the only laboring class we have."

Meanwhile, in Pulaski, Tennessee, six Confederate veterans had formed, as a lark, a secret society that they whimsically dubbed the Ku Klux Klan (from the Greek word for circle, kuklos — they evidently liked the mystical ring of the alliterated k's.) At first, the six men and their recruits undertook non-violent, theatrical stunts to frighten back into line the freed slaves just beginning to assert their new rights. But soon enough, more men joined the KKK and, as Republican efforts to rehabilitate Southern society grew more concerted, the KKK became a violent, marauding organization whose individual "dens" answered to no centralized authority. Society was changing quickly, and the KKK was trying to slow the pace. Bodies of freedmen, their white supporters, and Republicans began to litter the roadside.

It was at about this time that Forrest, learning of the KKK, expressed a desire to join. The eminent recruit was elected grand wizard, the Klan's highest official, and tried to bring the rapidly multiplying dens under a centralized authority — his own. Forrest probably did not object to the violence, per se, as a means of restoring the pre-war hierarchy, but as a military man, he deplored the lack of discipline and structure that defined the growing KKK. In its methods and aims, the KKK was merely the avenging ghost of the Confederate army. To Forrest's dismay, though, it was not an army that he could command.

After only a year as Grand Wizard, in January 1869, faced with an ungovernable membership employing methods that seemed increasingly counterproductive, Forrest issued KKK General Order Number One: "It is therefore ordered and decreed, that the masks and costumes of this Order be entirely abolished and destroyed." By the end of his life, Forrest's racial attitudes would evolve — in 1875, he advocated for the admission of blacks into law school — and he lived to fully renounce his involvement with the all-but-vanished Klan. A new, different, and much worse Klan would emerge, 35 years after Forrest's death, in the wake of D.W. Griffith's revolutionary 1915 film, Birth of a Nation, a reactionary screed with a racialist brief that had been expanded to include Catholics and immigrants of all kinds. The second Klan was never restricted to the South; its goals had nothing to do with Forrest's vision of a restored Dixie.

Nathan Bedford Forrest was a product of a divided society in which acts of racism were often considered good Christian behavior. He always suffered from a wild temper, bullied his subordinates and even his commanding officers, and was extremely violent. He grew up impoverished to a degree that few of us can imagine, and by ruthlessness and hard work rose to become one of the four or five most important actors in the American Civil War. Contemporary critics complained that he was ungallant, uncouth, and uneducated, not a grand Southern gentleman such as Robert E. Lee. Forrest himself would not have argued the point. But as a military mind and as a cultural artifact, Forrest is indispensable to a full understanding of the period.