From The Huntsville Historical Review, Winter-Spring 2000, Volume 27, No. 1.

Looking forward to the new century and a new millenium, Huntsville's artistic and scientific conununity has joined forces to initiate the "1999/2000 Von Braun Celebration of the Arts and Sciences." Undoubtedly, among the major milestones of the 20th century, man's daring and dramatic first flights into space and to the moon deserve full recognition and acclaim. Achieving these tremendous feats was in no small measure possible through the visions of Wemher von Braun and the technical and scientific accomplishments of his enthusiastic and capable rocket team. Their achievements changed the city of Huntsville from the "Watercress Capital of the World" to "Space City, USA" and added an exciting dimension to the quality of life in their new hometown.

The first major festivity of the Huntsville celebration will be the 30th anniversary of man's first landing on the moon. As the NASA-Marshall Space Flight Center's international relations specialist, I was most fortunate to have been involved in the behemoth activities at the NASA-Kennedy Space Center launch site prior to and on July 16, 1969. This was the day when Neil A. Armstrong, Edwin E. (Buzz) Aldrin, and Michael Collins started their lunar odyssey. The launch became a spectacular highlight for the Huntsville team and the entire NASA organization.

Overall management of and responsibility for the Apollo program was vested in NASA Headquarter's Office of Manned Space Flight, directed by George F. Mueller. A total of close to 400,000 persons in industry, NASA, and various government support agencies were involved in the lunar venture, reaching a new level of technical, scientific and managerial progress and competence. While overwhelming interest and publicity generally focused on the Apollo astronauts and their spacecraft, it was the giant Saturn V rocket designed by and built under the management of the Marshall Space Flight Center that provided the power for the flight to the moon.

The excitement of a truly historic event pervaded the hundred thousands of people who had come to Cape Canaveral and the adjoining coastal area to watch the launch. President Richard M. Nixon was at the Cape the preceding evening. He had dinner with the astronauts, but flew back to Washington immediately afterwards. At ten o'clock the same evening, Vice President Spiro T. Agnew flew in. He stayed at a private residence overnight, and the next morning a helicopter took him to the Launch Control Center where he observed the pre-launch and launch procedures.

To acconunodate all invited VIPs, media representatives and the large group of working and visiting NASA and contractor employees required painstaking logistical operations. Patrick Air Force Base activated additional control personnel for the arriving and departing airplanes and helicopters. Six thousand buses chartered by NASA stood ready to transport personnel to their work sites and visitors to the official viewing areas.

President Nixon had personally invited all members of the Washington Diplomatic Corps. The Vice President had invited 50 guests who arrived the morning of the launch. All members of Congress and their wives or guests had received invitations. So had the governors of every state in the nation. Lester Maddox, then governor of Georgia and famous for his fried chicken eatery, had the nerve to ask for thirteen extra admissions! Eventually he got them. Life Magazine had flown in the presidents of the 50 largest U.S. companies. NASA Administrator Thomas O. Paine and his staff and the directors and managers of all NASA Centers were present. Over 3,000 media representatives including newspaper and TV personalities from 56 foreign countries had arrived. Walter Cronkite of CBS, with his TV crew, occupied a separate enclosed area at the Press Site. All major television networks and stations were there for live reports from the Cape.

I spent the day of the launch in illustrious company. At 5:00 a.m. Wernher von Braun, Cornelius Ryan, the noted author, and I climbed into a helicopter waiting for us behind the Holiday Inn in Cocoa Beach to fly to the Melbourne Airport. It was still pitch dark when we took off. At the launch pad the huge three-stage Saturn V with the Apollo capsule on top was illuminated by a series of searchlights forming a brilliant sight against the dark sky, a truly awesome sight. Arriving at the Melbourne Airport, we met a French jet chartered by the worldrenowned Paris Match magazine. The passengers included Sergeant Shriver, U.S. Ambassador to France, and 80 high-ranking European industrialists, scientists, journalists, and other VIPs. We joined them for breakfast at the airport restaurant where von Braun officially greeted the guests in French and English. Afterwards, von Braun and Ryan left by helicopter to the Launch Control Center, while I escorted the European group to the VIP viewing site.

Regular announcements from Launch Control constantly informed the visitors of the status of pre-launch activities. When the actual countdown fmally started and reached 5, 4, 3, 2, and eerie, apprehensive calm set in. At -1, the engines were ignited. Their flames became a huge fireball that lit the scene like a rising sun. No sound was heard. At last, at zero countdown, the roar of the Saturn V engines started to fill the air. When the holddown clamps were released, the space vehicle slowly began to move upward. The tremendous blast-off made the earth tremble and reverberated in the bodies of everyone on site. Seeing the majestic lift-off turned the silent awe of the viewers into a thunderous applause. The gigantic vehicle rose higher and higher in to the air until it escaped the viewers' sight. Launch Control announced that the first and later the second state with the Apollo capsule and the Lunar Excursion Module had arrived in tile projected earth orbit. Eventually, another firing of the third state engine boosted Apollo 11 onto its lunar trajectory. The Marshall team and the Kennedy Center personnel directed by Dr. Kurt Debus had accomplished the tremendous task they had set out to do! From then on, the astronauts' daring voyage would be controlled and directed by the Mission Control Center of the NASA-Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, the home base of the astronauts. Director of this Center was Robert H. Gilruth.

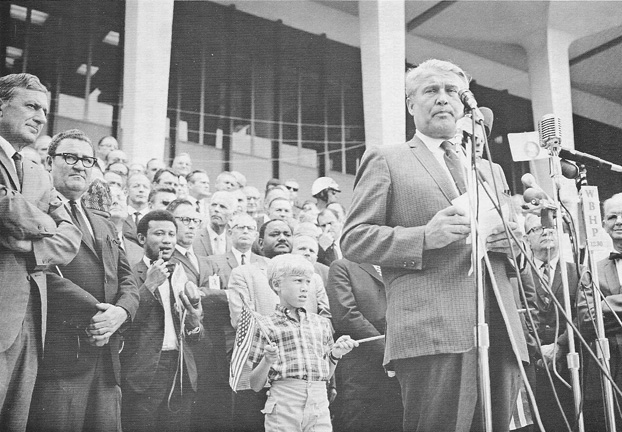

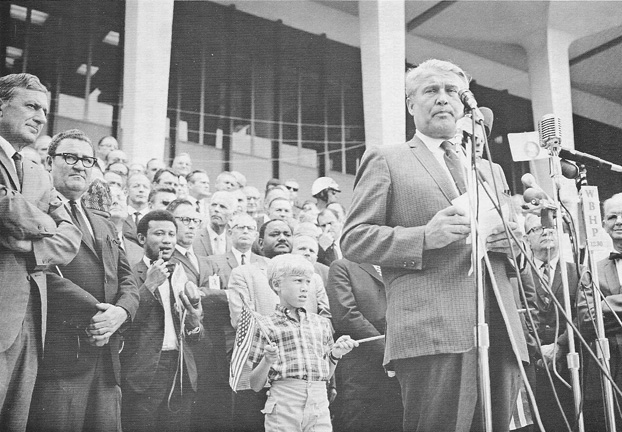

July 20, 1969, the day the Lunar Module landed on the moon and Neil Armstrong took his first step on the lunar soil, has become one of the most remarkable dates of this century. I believe most of us will always remember where we were when Neil Armstrong spoke the famous words, "That's one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind." A day later, the entire NASA team watched with great apprehension the critical lift-off from the moon, the only phase of the flight for which no back-up system or rescue procedure existed. It was a tremendous relief to see the Lunar Excursion Module leave the lunar surface and join the orbiting Apollo capsule. The final safe return and splashdown of Apollo 11 in the Pacific Ocean occurred on July 24. Only then could the Marshall team and the entire nation truly rejoice in the success of the mission. Full of enthusiasm and pride, thousands of Huntsvillians gathered that day in front of the Madison County Courthouse to celebrate the historic event and honor von Braun and his team. In the evening, Marshall Center and contractor employees together with Huntsville notables and friends staged an exuberant celebration that lasted into the wee hours on the tarmac and in the hangars of Huntsville Aviation.

While the Apollo 11 lunar odyssey was undoubtedly the most spectacular event in NASA's and the Marshall Center's history, there were many other unique space highlights which emanated from Huntsville. In fact, Huntsville's rocket and space history dates back to 1949 when the U.S. Army selected Redstone Arsenal as the location for its rocket and missile development. Subsequently, in 1950, the Rocket Research and Development Office of the Army Ordnance Corps in Fort Bliss, Texas, was transferred to its new location. The group headed by Col. James P. Hamill included von Braun, members of his former German rocket team, and their American counterparts. Their families also moved to their new home town.

At Fort Bliss and the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, the members of the Rocket Research and Development Office had conducted firing tests and upper atmospheric research flights with captured German V-2 rockets. On February 24, 1949, a V-2 with a Wac Corporal second stage provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, had achieved a record altitude of 244 miles.

Several of the German rocket experts had already begun with von Braun in the late twenties and early thirties privately funded rudimentary testa of small liquid fueled rockets in and near Berlin. During World War II they had been involved with a large government and contractor team in the development of the world's first large ballistic missile, the A-4. It saw its operational and destructive use under the designation V-2 (Vengeance Weapon 2) in the [mal months of Hitler's gruesome and disastrous military venture.

The A-4 represented a remarkable breakthrough in rocket technology. It was the first rocket ever to reach the fringes of outer space. Recognizing the unique experience and capabilities of the von Braun team, Col. Holger N. Toftoy, after the end of the World War II, arranged for von Braun and about 120 scientists and engineers to be transferred to the United States. However, it was only after the move to Redstone Arsenal in 1950 that the group was assigned a major new project-the development of the intermediate-range Redstone missile. In due time the development of the larger Jupiter missile followed. Challenged by the new assignment, the members of the group set out with great drive and efficiency to plan, develop, test, and launch America's first heavy ballistic missile. The first launch of the Redstone took place August 20, 1953, from Cape Canaveral, and the first long-range Jupiter missile was launched May 31, 1956.

In August 1957, the Huntsville rocket team achieved another milestone-the first recovery of a rocket nose cone after its flight into outer space and its fiery re-entry into the atmosphere. The innovative use of ablative material which melted during the intense heat upon re-entry into the atmosphere protected the nose cone and provided assurance for a safe return of future space hardware. While developing missiles for the military, the idea of exploring space and using rockets to send unmanned and manned spacecraft to our planetary neighbors was always in the back of the minds of von Braun and his team Space flight became a constant topic of conversation among the group. It also became the focus of meticulous studies and the subject of many articles and speeches by von Braun. In 1953 Collier magazine, a then very popular illustrated magazine, published a series of articles describing von Braun's idea of a space station. The series was edited by Cornelius Ryan and had some fantastic illustrations by Chesley Bonestell. Some of Bonestell' s original art has often been on display at the local U.S. Space and Rocket Center.

Upon publication of the series, von Braun was invited by CBS. to ap~ o.n national television and discuss his ideas of space stations and satellites. While his appearance attracted some attention, the idea of space flight did not yet g~ popular acceptance. Even in Huntsville opinions about the rocket team and their dreams of space were rather mixed. It certainly was great seeing the Arsenal reactivated and attracting an ever-growing number of professional people, but von Braun's visions were still far beyond the expectations of Huntsville's citizens.

Serious thoughts of launching an artificial satellite as part of America's contribution to the International Geophysical Year 1957-58 evolved in the mid fifties. Von Braun and members of his team participated in the preliminary discussions and made proposals on behalf of the Army. Their satellite proposal, known as Project Orbiter. was put forward in conjunction with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the Naval Research Office. It called for a satellite weighing roughly 20 pounds to be launched by a Redstone missile with upper stages of clustered solid-fuel rockets.

For various political reasons President Dwight D. Eisenhower decided against the use of a Huntsville developed Redstone missile. He declared that America's contribution to the International Geophysical Year should not involve existing military hardware. Instead, the Vanguard Project was initiated with a Viking rocket as launch vehicle. Among the members of the local rocket team, the disappointment was great. But they did not give up their ideas to launch a satellite with one of their rockets, and worked on improving their own plans. Under a shroud of secrecy and with the daring encouragement of Major General John Bruce Medaris, Commanding General of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency, and von Braun's boss, preparations were made to modify a Jupiter rocket as launch vehicle for a package of instruments to be developed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

On October 4, 1957, a surprise and shock hit the western nations. Soviet Russia had succeeded in launching the world's first satellite, Sputnik I, thus marking the spectacular beginning of a new era. Shortly thereafter, on November 3, 1957, the Russians launched Sputnik II, carrying the dog Leika into an earth orbit. Both events electrified the world and almost panicked the American people. American leadership in science and technology had been challenged. In Huntsville, frustration and disappointment among the rocket team rose. Medaris and von Braun resumed their pleas for a chance to launch a satellite, but no immediate approval was forthcoming.

Meanwhile, the Vanguard Project, gauung in urgency, encountered serious difficulties. After a series of failures and blow-ups on the launch pad, Secretary of Defense Charles E. Wilson finally gave the Army the green light to launch two satellites. The local team was to get a chance after all.

On January 31, 1958, four months after Sputnik I, Huntsville's Jupiter-C sent Explorer I, the western world's first satellite into orbit. Its 15 pound payload made a remarkable discovery. It detected a radiation belt existing around the earth, instantly named after James Van Allen who had been in charge of developing the scientific payload. When the news of the successful Explorer launch reached Huntsville, thousands gathered to celebrate. There was dancing in the streets, celebrations everywhere and great exuberance. Explorer I represented a breakthrough for the local rocket team, and Huntsville became the focus of worldwide attention. The city began to call itself "Rocket City USA: and "The City where Space Began."

It was at that time that I received an offer from the Army Personnel Office to join the von Braun team as translator. My initially temporary job was to review and reply to the stacks of congratulatory telegrams, messages, and interview requests from abroad. On an unpaid basis, I had already done some translations of foreign correspondence for von Braun. To work officially with the Development Operations Division was a wonderful opportunity and challenge that I was delighted to accept. While I had worked as secretary and translator for the French subsidiary of a German firm in Paris, I had no American school and employment record. I needed to pass a Civil Service translator test. Unfamiliar with American testing methods, government lingo and even many idioms, I flunked the first test Fortunately, I could take another test four weeks later and managed to squeeze by. My temporary employment had begun already in February 1958. In the course of years, it expanded into an intriguing permanent Civil Service position as public and international relations specialist with many diversified and unique assignments. I learned a tremendous amount from my journalist colleagues, supervisors, and, of course, directly from von Braun who has a master in written and oral communications and a skillful and brilliant manager. With his broad range of knowledge and interests, keen curiosity, awareness of the past and visionary focus on the future, he was indeed the modem version of a Renaissance man. In his spare time in Fort Bliss, he had already sketched and published his vision of a future manned trip to Mars.

The exuberance over the successful Explorer launch created a wonderful spirit of camaraderie and cooperation among the members of the Army. Ballistic Missile Agency. However, not everyone felt certain about manned flights into space. A clever little ditty made the rounds among the employees, reflecting the then prevailing mood. The title and text were:

MEDARIS, VON BRAUN AND MEIn the missile game we've won great fame The world knows our Jupiter-C.

And what we've done with Explorer I Medaris, von Braun and me.

Oh, watch our smoke as we go for broke To solve the space mystery.

We have a thirst to be there first, Medaris, von Braun and me.

Our skill we pride, we can travel wide Into space so wild and free.

To the moon, then Mars, then to distant starts Medaris, von Braun and me.

When finally we've planned a space ship that's manned And they call for brave men - two or three

To try first for the moon in that metal balloon, Call Medairs and von Braun - NOT ME.

During the following years many more firsts in space were achieved by the Huntsville team. Pioneer IV launched March 3, 1959, became the free world's first satellite of the sun. The first flight of animals in a U.S. ballistic missile and their recovery took place in May 1959. Two monkeys, Able and Baker, traveled into space in the nose cone of a Jupiter missile and were safely returned. For a long time, Miss Baker enjoyed public attention and good care as monkey-in residence at the local Space and Rocket Center.

After Congress began to recognize the political, scientific and economic potential of space activities, it officially established the National Aeronautics and Space Administration in 1958. President Eisenhower signed into law the Space Act and assigned the National Aeronautic and Space Administration to conduct the nation's civilian aeronautical and space program. In 1960, on July 1, the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center was established and activated through the transfer of buildings, land, personnel, and space projects from the Army.

The Center was named in honor of General George C. Marshall, the Army Chief of Staff during World War II, Secretary of State, and Nobel Prize winner for his world-renowned Marshall Plan. Wernher von Braun became the Center's first director. For the formal dedication, President Eisenhower personally visited the Center and the widow of General Marshall attended the ceremonies.

NASA's first ambitious manned space flight venture was Project Mercury. Seven of the best qualified military test pilots were chosen as the first group of U.S. astronauts. The Army's Redstone rocket was to serve as launch vehicle for the first suborbital flights. For later manned orbital flights the heavier Atlas booster of the Air Force was selected. The Mercury capsule was developed by the McDonnell Company.

Before any American astronaut had a chance to fly into space, the Russians again stole the show. On April 12, 1961, the official Soviet News Agency TASS announced: "The World's first spaceship Vostok with a man on board has been launched in the Soviet Union on a round-the-earth orbit. The first space navigator is Major Yuri Gagarin. After a lOS-minute flight he landed intact near the Volga River, some 15 miles south of the city of Saratov." Gagarin's flight proved that man can retain in space his capacity for work, coordination of movements, and clarity of thought. Even more importantly, his flight alerted the entire world to Russia's technological advances and the inherent threat of her ballistic missiles to western security.

The shock of seeing the Russians gain another victory in space gave the modest initial U.S. space efforts a tremendous push and a much greater priority. Congress began to realize that America's venture into space had to be expanded. Space had become a symbol of world leadership. The space race had begun. Huntsville's role as space age city was to grow in importance and scope.

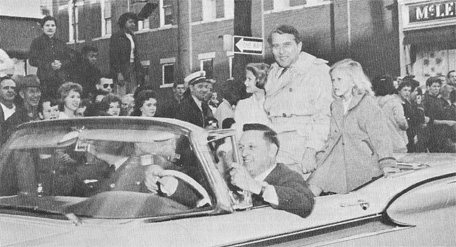

For the first Mercury launch, extreme caution on the part of NASA in man-rating the Redstone rocket was exercised. After considerable delays, the first Redstone booster capped with a Mercury spacecraft manned by astronaut Alan B. Shepard lifted off its pad at Cape Canaveral on May 6, 1961. After its IS-minute flight, the Mercury capsule Freedom 7 landed about 300 miles downrange from the Cape. Recovery operations proceeded perfectly and Shepard was in excellent condition and exuberant. No less exuberant were the Marshall Center team and the citizens of Huntsville who staged a grand salute to Shepard and von Braun on the downtown square.

In view of Gagarin's orbital flight, the Mercury I mission had been somewhat anticlimactic. But it chalked up an impressive first for the U.S. It reflected a remarkable degree of technical excellence and established a hallmark of open media reporting. In contrast to the secretary surrounding all Russian launches, full press and TV coverage existed for the Mercury flight and was to exist for all subsequent NASA space launches. The American public and the rest of the world were able to witness and appreciate the complexity and drama of man's early venture into space.

After another Redstone booster had launched Captain Virgil 1. Grissom on a suborbital flight in July 1961, the Mercury program approached its climax. On February 20, 1962, an Atlas booster of the U.S. Air Force launched Col. John H. Glann, Jr., in his Friendship 7 capsule on its historic first orbital flight. After three orbits, a slightly worrisome re-entry and splashdown in the Atlantic Ocean, Glenn was recovered safe and sound. A grateful nation showered him with honors and lined the streets in New York and Washington to cheer its new space hero. The Huntsville team, although not directly involved in the Mercury orbital flights, joined in the pleasure of seeing another milestone in space achieved.

In May 1961 shortly after the successful first Mercury flight and the debacle of the Bay of Pigs, President John F. Kennedy presented a special message to Congress. He asked that the nation commit itself to achieving the goal, before the end of the decade, of landing man on the moon and returning him safely to earth. The lunar mission was to present to the world a new image of American strength, destined to surpass the Soviets who had clearly been the leader in space so far.

Congress quickly endorsed the President's proposal and the Apollo Lunar Landing Program was initiated, vastly increasing the scope and pace of NASA's activities. At the Marshall Center, under the brilliant and enthusiastic leadership of von Braun, a dynamic phase of development began. The Marshall Center was to develop the heavy Saturn launch vehicles to carry man to the moon. Already under Army management, the von Braun team had begun the development of a large clustered rocket stage. Work had also begun on the development of an upper stage using hydrogen instead of the less powerful kerosene, and the construction of a major launch site at Cape Canaveral was initiated. Following these preliminary steps, the development of the huge and sophisticated Saturn rockets proceeded with remarkable speed and fantastic results. No a single Saturn vehicle ever failed in the 14 years of its testing and use in unmanned and manned space missions.

Three different Saturn configurations, Saturn I, Saturn IB, and Saturn V, were to be used in the Apollo program. Saturn I's were launched for research and test purposes. Three Saturn I flights also sent three Huntsville-developed large meteoroid detection satellites into orbit They determined that danger from the possible impact of meteoroid particles on future spacecraft was negligible. The Saturn ill, a more powerful launch vehicle, was used for orbital tests of the Apollo spacecraft. But only the giant Saturn V, whose first stage produced the tremendous thrust of 7.5 million pounds, would eventually be able to place the Apollo spacecraft into a lunar trajectory.

While work on the Saturn vehicles proceeded at the Marshall Center, President Kennedy, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, and NASA Administrator James E. Webb visited the Center on September 11, 1962. They toured Marshall laboratories and were briefed by von Braun on the status of the Saturn program. The same year von Braun and state and local dignitaries broke ground for the University of Alabama in Huntsville's Research Institute, initiating a great expansion of Huntsville's educational and research facilities.

On April 16, 1965, the first full static test firing of a Saturn V first stage took place at the Marshall Center. It proved to be a full success and a remarkable display of harnessed rocket power. Many Huntsvillians may remember hearing the tremendous roar whenever static firings were conducted in the Center's test area. In later years, most of these tests were conducted under the Marshall Center's direction at the newly established Mississippi Test Facility in Hancock County, Mississippi.

During the first half of the sixties, a vigorous expansion took place in the city of Huntsville to provide space and services for the many thousands of persons who were moving to the city due to the lure of the space program. By 1966, the Marshall Center's personnel strength reached about 7500 employees. In addition, approximately 5300 contractor employees worked for the Marshall Center on Redstone Arsenal. Space had become big business in Huntsville. The Center's total budget for fiscal year 1966 was $l.8 billion, of which more than 90% went to industry in Huntsville and other locations allover the country. From about 17,000 persons in 1950, Huntsville's population was to grow to more than 140,000 in 1970.

The year 1966 saw three successful unmanned flights of the Saturn IB launch vehicle. On two of these flights, full systems of the Apollo command and service modules were tested in earth-orbital operations. Dramatically, on January 27, 1967, tragedy struck the Apollo program. A fire erupted inside an Apollo spacecraft during ground testing at Cape Kennedy, resulting in the deaths of astronauts Virgil Grissom, Edward White II, and Roger Chaffee. This was a frightening loss and serious setback. The board of inquiry determined that the most likely cuase of the fire was electrical arcing from spacecraft wiring. After an extensive investigation, NASA undertook detailed corrective actions and modified schedules and cost estimates in order to keep the Apollo program on track.

To support the required changes in the Apollo capsule, Eberhard F. M. Rees, von Braun's deputy, was sent to the Downey plant of North American Aviation as troubleshooter. Rees saw to it that even the tiniest element of the Apollo capsule was duly tested and utmost reliability achieved. Huntsvillians, who remember Rees, will also recall his dry humor. At a dinner in his honor, he commented that von Braun had been a great troublemaker in his life. If it had not been for von Braun, he could have enjoyed an easy and peaceful life with a nice fat wife and a soft job as postmaster in his small hometown of Trossingen in Germany.

October 1968 saw the first manned Saturn! Apollo flight with a Saturn IB as launch vehicle. Apollo 7 with astronauts Walter Schirra, Don Eisele, and Walt Cunningham performed flawlessly. After 11 days in orbit, splashdown in the Atlantic Ocean was within 10 miles of the predicted area. Two months later Frank Borman commanded the first flight around the moon, televising views of the lunar surface for direct reception on earth. The pictures of the barren moon and the small blue earth as seen from lunar orbit were spectacular. On Christmas Eve 1968, while circling the moon, Borman, a devout Presbyterian, recited the story of creation from Genesis, providing a deeply touching experience for millions of television viewers. All systems of the Apollo capsule performed flawle~sly and Apollo 8 was safely recovered on December 27, 1968, after 147 hours m space.

Of course, the following year was to see an even more spectacular event, the launch and first landing of two Amencan astronauts on the moon. Six Apollo flights were to follow. One, Apollo 13, never to to thelunar surface because of a ruptured oxygen tank in the Apollo Service Module, but the crew made it safely back to a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean.

A total of twelve astronauts roamed the moon, by foot and by Lunar Rover. The Lunar Rover was a jeep-type vehicle conceived by Marshall Center engineers and developed under the Center's management to expand the astronauts' range of exploration on the lunar surface. Sixty experiments were placed on the moon and 850 pounds of soil and rocks were carried back by the astronauts. The lunar material investigations provided a wealth of data about the composition of the moon and its space environment. The last lunar mission, Apollo 17, was successfully completed in December 1972 by astronaut Eugene A. Cernan and his crew.

In the eyes of the world, America had again become the leader in science and technology. But not only prestige had been gained by the Apollo program. It had achieved what it set out to do. It developed a broad-based space flight capability for scientific and utilitarian purposes. It provided new knowledge and innumerable spinoffs in many disciplines. Computer technology, microcircuitry, materials research, communications and medical technology are some of the areas which have seen remarkable technical growth and economic benefits due to the space program.

After Apollo, what happened in space during the remainder of the 1970s? Proposals for a manned mission to Mars failed to receive congressional support because of the staggering complexity and costs of such an ambitious undertaking. A more modest, but still challenging project aiming at routine and more economical access to space was initiated, the development of a reusable Space Shuttle. Also, various unmanned scientific space probes, many of them developed in Huntsville, reached out into the vastness of our solar system and provided new data on its inner and outermost planets. Satellites for communications, weather forecasting, environmental studies, and astronomical and earth observations became commonplace.

Huntsville, with sincere regrets, saw the departure of von Braun to Washington in March 1970. He transferred to NASA Headquarters to accept the position of Deputy Associate Administrator for Planning Future U.S. Space Missions. He retired from NASA in June 1972 to become Vice President for Engineering and Development at Fairchild Industries in Germantown, Maryland. Until his untimely death in June 1977, he remained a forceful spokesman for the space program.

In 1973, Huntsville's rocket and space team performed another space spectacular. It launched Skylab, America's first large experimental space station. Skylab was conceived and designed by the Marshall Center team. Instead of the cramped quarters in the Apollo capsule, Skylab offered the astronauts plenty of room for living, working, and sleeping in space. Three successive crews of astronauts spent a total of 177 days in Skylab. They demonstrated that man can perform valuable services in earth orbit as observer, scientist, engineer, and repairman. The Skylab missions gathered more knowledge about the dynamic processes of the sun than had been collected in all preceding centuries. They also gave us a broad view of earth from space and helped define the feasibility of making new products in microgravity.

In 1975, the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project captured the attention of the world. For this mission, the Huntsville team provided a Saturn m launch vehicle. The successful docking between an Apollo Command Module and a Soyuz Capsule was the first demonstration of international cooperation in space. It took many years before a valuable partnership with Russian astronauts and their space systems were to follow.

For the remainder of the decade, the Marshall Center focused on developing and testing propulsion systems and payloads for the Space Shuttle, working toward the future realization of the Hubble Space Telescope and various space science experiments. During the spring of 1978 the first assembly of a complete Space Shuttle-he Orbiter Enterprise, external tank, and two solid rocket boosters-was done at the Marshall Center. The huge vehicle underwent months of extensive ground testing in the Center's dynamic test tower to verify its flight readiness. In addition, intriguing new concepts and tests were initiated for the utilization of the European-built Spacelab to be flown on the Shuttle in the 1980s.

The long-awaited maiden flight of the first reusable Space Shuttle Started on April 12, 1981, from Cape Kennedy and opened the era of continuing extended space activities for successive astronaut crews. In the coming years one of the Shuttle's major tasks will be to put into space the elements of a large international space station and the crews to assemble it, and to conduct a multitude of ambitious scientific and technical experiments for the benefit of all of us on the planet earth.

For the immediate future, NASA Administrator Daniel' Goldin is pushing his agency's mission to become "faster, better and cheaper." Truly spectacular manned missions to far-away Mars may have to wait for a renaissance of America's quest for new horizons. But the road to the stars has been opened and the fascinating evolvement of man's flight into space has become part of Huntsville's history.

BIBLIOGRAPHYSelected information taken from the following publications and notes:

Wernher von Braun, "Reminiscences of German Rocketry," Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, Vol. 15, No.3, May-June 1956.

David S. Akens, Origins of the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center, NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, AL, December 1960.

Wernher von Braun, "The Redstone, Jupiter and Juno," Technology and Culture, Vol IV, No.4, Fall 1963.

Gordon L. Harris, "Public Interest in Apollo 11 Launch." Memorandum of talk to Kennedy Space Center personnel, July 3, 1969.

Office of Public Affairs, NASA Headquarters, History of Manned Space Flight, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1977.

Ruth G. vonSaurma and Walter Wiesman, The German Rocket Team, Alabama Space and Rocket Center, Huntsville, AL, August 1983.