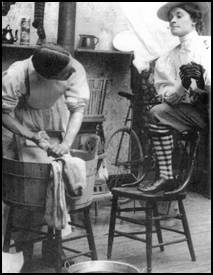

At the beginning of the 20th century, women wanted to participate in the world around them. Up until that time, women could be acknowledged publicly on only two occasions: at marriage and with their death. For instance, on Judge George W. Lane's mother's tombstone, he had written simply, "My Mother." For instance Daniel Hundley's 361-page book written in 1860, Social Relations in Our Southern States lists the chapters that he would write about from first-hand knowledge. He begins with, to no one's surprise, The Southern Gentleman, then, The Middle Classes, The Southern Yankee, Cotton Snobs, The Southern Yeoman, The Southern Bully, Poor White Trash, and The Negro Slave. Women, black or white, were lucky to be noted interspersed anywhere within his text. However he understood the one sacred institution, "…a Southern matron is ever idolized and almost worshipped by her dependents… to whom no word ever sounds half so sweet as mother and for whom no place possesses one half of the charms of home." She "…faithfully labors on in the humble sphere allotted her of heaven - never wearying, never doubting, but looking steadfastly …to God for her reward." Life for women will only be good at her death?

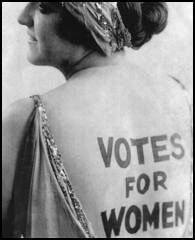

The long, hard fight to achieve suffrage for women in the United States, and eventually Alabama, began in 1848 when Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, and others met in Seneca Falls, New York to form the first public protest against women's political, economic, and social inferiority. The demand for suffrage quickly became the central issue in the women's rights movement. Newspapers throughout the state immediately voiced their opposition. Things were different in the south. Southern women were not expected to "bother their pretty little heads" about day-to-day affairs whether uneducated countrywomen or sophisticated town ladies.

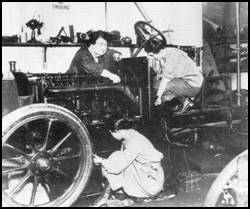

Historically, Southern women were not as socially organized as their northern counterparts, however the ladies at the home-front during the Civil War initiated relief societies to provide bandages, clothing, and supplies for their men at the front. In Mobile a society formed to provide clothes for the needy children of Confederate soldiers. Women soon volunteered to become nurses in the field and organize hospitals, a job formerly considered to be a male occupation. Alabama's Sallie Swope, Kate Cummings, and Juliet Opie Hopkins were among the many hundreds who served. (In this new field of service Dorothea Dix suggested female volunteers should be over 30 and preferably plain of looks.)

As the Civil War continued, women organized in Mobile for a more immediate crisis. In 1863 amidst famine, women carried signs reading "Bread or Blood," and Confederate soldiers kindly looked the other way as the women looted bread stores to feed their children. Desperate "corn women" in Alabama gravitated to the Black Belt and stripped the productive fields of corn and grain to take back to their starving families.

With their fathers, brothers, and husbands away, women faced hardships and challenges during the War years that also increased their share of responsibility. In most cases women assumed the management of the farm or the town house and found, even if they didn't want to, they could perform these tasks.

After the War women helped rebuild churches and formed missionary societies. There was so much that needed to be done. Religious activities naturally led to and established the validity of their ventures into the public arena. Furthermore, as the South tried to reestablish itself, women were lured to the drama of their Lost Cause. Many patriotic groups formed and reunions were held for veterans. For the ladies, the Daughters of the Confederacy became a powerful social organization. Within a different setting, rural white women were allowed to hold office in the local Grange, and in the Farmers' Alliance.

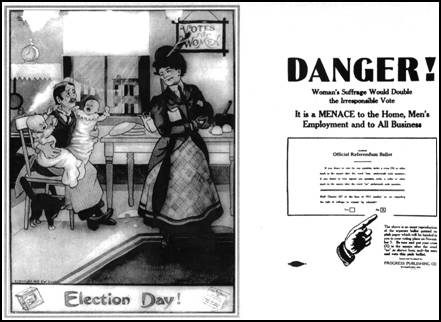

By 1890 the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was formed, and the movement slowly found its way into the South. The myth of Southern womanhood made the fight for the vote in the South very difficult. Remember that, in the past, essential female qualities were to include beauty, gentleness, modesty, domesticity, moral superiority, and submission to the doctrine, of - what else - male superiority and authority.

In the Victorian era, however, many of the life experiences acquired during the Civil War had faded from view. Women were again admonished to be submissive, and they were expected to reign only over domestic life. Ah, the Victorian woman, from all appearances, was wrapped tightly in corsets and long skirts that hid her legs as the legs of the pianos were draped from a roving eye. Women who showed discontent or protest were often ridiculed, or worse, considered not to be ladies at all. As a result, the ordinary lives of most Alabama women at the new century did not extend far beyond home, fields, church, and a few occupations. One might aspire to be a teacher, secretary, or a nurse, but more likely women served as a beautician, seamstress, cook, maid, or washerwoman.

In Huntsville two female members of the prominent Clay family, after their father's stroke, had taken over complete management of the family newspaper, the Huntsville Democrat. In 1892 Susanna Clay, as associate editor, attempted to attend a public program at the Court House. One of the speakers, Mr. E. J. Taliaferro from Birmingham, objected to a lady being in the audience while he spoke. Miss Clay reported to her readers she did not mind missing his speech, but she felt any citizen should be admitted to hear the speakers - Gen. Edmond W. Pettus, U. S. Senator and Honorable A. C. Hargrove, president of the Alabama Senate.

Miss Clay attended as a reporter, a working female, and this was clearly a man's job to Mr. Taliaferro. She was making herself masculine by this appearance. "If she put herself in a man's place she should be treated as a man," stated Taliaferro.

"Exactly," she said. "I should be admitted to public meetings exactly as any man."

Her reply only inflamed the enemy for, "A female should not practice that type of repartee."

In 1894 Virginia Clay-Clopton and other women founded the Huntsville League for Woman Suffrage. Within two years Mrs. Clopton became president of the Alabama Woman Suffrage Association. The group was small but sincere. Like many other communities Huntsville struggled with the issue of woman's suffrage. Mrs. Milton Humes had often entertained local political leaders for her husband; she knew how to organize. She understood how the system worked, and she and her friends resisted the influence of the Huntsville Weekly Mercury. This newspaper asserted that involvement with politics, just as women daring to ride bicycles, would strip them of all femininity.

Through the efforts of Ellelee Humes and Alberta Chapman Taylor, the town was about to be in a tizzy. These women - daughter and sister of former Governor Reuben Chapman - led the social scene in Huntsville. Excited by the time she had spent in Colorado, Mrs. Taylor was already filled with the success of the 1893 suffrage campaign there. Suffragists Miss Susan B. Anthony and Mrs. Carrie Chapman Catt were invited to speak in Huntsville on January 29, 1895. The town quickly was abuzz with this bold staging.

How dare they? How could women be involved in politics? What would become of their babies if mothers were out campaigning - who would prepare meals for the men folk? And yet keen observers pointed out that, at Dallas Mills, mothers already were away from the home from six in the morning to six at night, and no one asked who was taking care of their children. Furthermore, to keep from having unattended children at home, the cotton mills were quite willing to hire their youngsters for the same ten-to-twelve-hour day.

In the week before the women's appearance, the Mercury continued to print its opinion. The editor noted he was anxious for Huntsville to enjoy every modern convenience and believed there was nothing too good for its people, but there were some things which were not good enough: the "Wimin" Suffragist party, for instance.

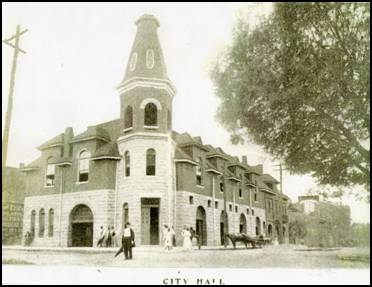

An overflow crowd filled the auditorium of City Hall, then at the corner of Washington and Clinton Streets. During the daytime the ground floor of the brick and stone building served as the municipal market for farmers. For this special evening, a wooden platform had been built at the far end of the meeting space. The hall was tastefully decorated, with bunting and Jackson vine around the newly completed stage. Capt. Milton Humes and Mrs. Humes, Mr. Ben P. Hunt, and Mrs. Alberta Chapman Taylor escorted the speakers, accompanied by sparse, even anxious, applause from the audience. Already in her place on the stage was the indomitable Virginia Clay-Clopton, now 70. The crowd, except for a few supporters, had not come to be convinced; they were there to see the show. No one really expected to be converted.

The nation's foremost suffragist, Miss Anthony, soon to be 75 years old, spoke first and gave the history of the progress of women's suffrage during her lifetime. No one could find offense at her appearance; she was slender figure in a simple dress, with wire-frame glasses and a bun of straight silver hair. She looked like an elderly schoolmarm, perhaps, even harmless. She appeared to be speaking to a friendly audience, although some may have uncomfortably squirmed in their seats perhaps trying not to be recognized by their neighbors as having a favorable reaction. However Miss Anthony (left) was warmly applauded, paving the way for the second speaker.

Carrie Chapman Catt (right) truly charmed her listeners. Mrs. Catt, about 35, was stylishly dressed, assertive and confident. Her speech was eloquent and dramatic, and she captivated her listeners, drawing rounds of applause during her 75-minute talk. One listener said, "I have never heard any speaker, not even William Jennings Bryan with the flow of language that Mrs. Chapman Catt had…. It was like listening to silver waters purling over a rocky bed. It was incessant beauty; music in the making." Afterwards Captain Humes invited members of the audience to come forward and enroll in the Huntsville League for Woman Suffrage. A number of ladies and several gentlemen did so.

In varying degrees the local newspapers were impressed. Although not easily convinced, Editor O'Neal of the Weekly Mercury acknowledged Miss Anthony "spoke with ease and presented her facts in a plain direct and coquettish manner." The Mercury did not comment on her supposed lack of femininity with his use of the word "coquettish." Of Mrs. Catt he wrote she had a "charming personality, intelligent culture and eloquence, which completely captured the large audience and held them charmed, from the open to the close of her remarks which lasted an hour and fifteen minutes. From her standpoint her position and argument are almost unanswerable." Faint praise, indeed.

However, the Mercury's position was adamant. "The Southern ladies will never endorse the movement, preferring as they do to preside as queens in the hearts and homes of the men they love…. Their duties to God, their families and society sufficiently employ the minds of true Southern women, without entering the political arena."

The Tribune editor, Charles P. Lane, noted Miss Anthony's "unanswerable questions" and Mrs. Catt's cultured intelligence. The editor thoughtfully considered, "Women may yet be the means of preserving our free Republican institutions in America. Who knows? Stranger things have happened."

Having already visited Decatur, the women completed their Southern tour and went on to Atlanta for the 29th annual convention there. In 1898, however, Virginia Clay-Clopton gloomily noted, "Opposition is so great that it has been deemed wise to do nothing more than distribute literature and present the arguments in the press."

The battle continued in Gadsden with the column entitled, "A Matter of Regret." There the Times-News wrote, "It is regretted that a few of the leading women of Alabama are making themselves ridiculous by organizing a branch of the Women's Suffrage party. They may be conscientious and earnest in the movement, but they should remember that a woman's sphere is the home and not in the corrupt political parties of today. Let her stay at home and with a mother's influence raise the standard of politicians. The good women of the South do not want the power to vote - and any attempt to organize a 'wimmins right party' will be useless…. No man that ever fought for the South and its women can believe that they desire to enter a political life, which is necessarily corrupt." Perhaps the Gadsden newspaper revealed more than its readers really wanted to know.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Alabama prepared to write a new

Constitution for the state. Amazingly, future U.S. Senator "Cotton" Tom Heflin invited Miss Frances Griffin, president of the Alabama Equal Suffrage Association to speak at the state Constitutional Convention of 1901. (You will remember that Cotton Tom Heflin originated the phrase, regarding the ballot, "he would vote for an ole' yeller' dog if it was on the Democratic ticket.)

Miss Griffin assured the men that her group was seeking the vote for "good women…not the naughty, fast damsels, adventuresses and the like." There was prolonged applause from her supporters in the gallery but not from the delegates, and the proposal was defeated, 87 to 22. As former governor Emmet O'Neal pontificated, "Woman's suffrage was contrary to 'the theory of southern civilization,' which held 'that woman was the queen of the household and domestic circles…'" and should stay as such. The women, not defeated completely, bided their time. What next?

Women would lead a social revolution with issues of temperance, prison reform, social clubs, child labor laws, and women's voting rights. For this era of rapid change in an increasingly industrialized society presented a new set of social problems. Reformers attempted to alleviate these problems during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Recent historians have characterized the concerns and actions of women in the Progressive Movement as "social housekeeping - perhaps an extension of the traditional home-based role as nurturer and caregiver in a public sphere. And Alabama women would be a part of it all. But where and how should they begin?

The issue of temperance led the way. Once convinced that "demon rum" threatened the home, which was, of course woman's proper domain, the temperance movement quickly gained support. Reformers like Julia S. Tutwiler won the loyalties of traditional Victorian Southern women. (This remarkable woman had already persuaded the University of Alabama to open its doors to women in 1893, and then she lobbied, with other women's groups, to have female dormitories built.) And once the Temperance movement was organized, the numbers swelled to thousands moving from the private to public arena. Locally the need must have been great, in Huntsville Carrie Nation made an appearance - twice. The Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), as it was known became a powerful force.

This social network led naturally to the formation of women's clubs. More likely to be formed by affluent women, they studied public issues, read books and debated issues of reform. For example there was the Mobile Reading Club, the Tuscaloosa Kettle-Drum Club, Montgomery's 20th Century, and Birmingham's Cadmean and Highland book Clubs. (Cadmus, founder of Thebes introduced the alphabet to ancient Greece.) Alabama Federated Women's Clubs by 1895 had become one of the first umbrella federations combining 130 women in six clubs. By 1915 there were 153 clubs with 4250 members in the state. Black women formed a similar group four years later. The study of flowers, drama, books, music and art led to activity in civic and community problems.

With fervor women like Elizabeth Evans of Birmingham had the courage to teach Sunday school at the Pratt Coal Mine convict camp. Her enthusiasm led to the establishment of an industrial school for orphaned and troubled boys in East Lake. Lillian Orr and Nellie Murdock of Birmingham led the crusade to abolish child labor.

Perhaps one of the most sensitive issues taken on by the women was

that of the eradication of ruthless and dangerous child labor. Clearly within the realm of the family issues, the women now marshaled all their newly acquired social skills. Social worker, Nellie Kimball Murdock, served as chair of the Alabama Child Labor Conference. She and Mobile's Lura Craighead organized efforts to lobby in 1903.

The women, again led by Julia Tutwiler, became involved in the arena of prison reform. Her efforts spread to literacy courses for convicts, heating and sanitary inspections of prisons, separate prison facilities for women, and reform school for youngsters.

In Birmingham Martha Spencer lobbied for the poor. For over half a century she served on the board of the city Mercy Home that cared for poor women with tuberculosis, pregnant girls, orphans, transients, and delinquents.

Another female leader of this Progressive Era who saw needs in her own community and made a commitment for change was Sue Berta Rankin Coleman. Sue Berta was born in Huntsville where her widowed mother supported the family working as a cook for a white family. Somehow her mother was able to send this daughter to Fisk University, a private black college in Nashville. After her marriage, Mrs. Coleman moved to Birmingham, and began teaching in rural Jefferson County. In 1914 she moved into a company school system sponsored by a United States Steel subsidiary. She became the primary supporter of her family, now including four children. She worked for health programs and community activities. Mrs. Coleman became the first black community supervisor for the company. She considered the newly recruited workers from a rural setting to be like immigrants coming into a new environment. She borrowed money from a Bessemer bank, traveled to Chicago, and spent six weeks studying with Jane Addams, the renowned founder of the settlement house Hull House. On her return to Alabama, Mrs. Coleman was able to begin innovative programs in nutrition, kindergarten work, mothers' clubs, baby clinics, sewing, and library facilities for the families of black workers in the company town.

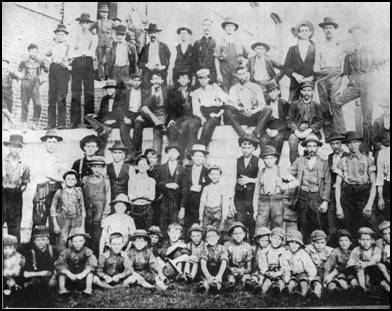

The photographs of Lewis W. Hine were critical in raising public awareness to the unacknowledged brutality of child labor. Pictures did not allow room for denial or ignorance of the harsh realities of the lives of American's working children.

Lewis Hine had photographed in the North - slums, coalmines and in the South - cotton fields, cotton mills, and coastal workers. Throughout the Deep South poor whites who sharecropped and tenant farmed were eagerly welcomed for new mill jobs. Entire families worked and lived in villages where they had company owned mill housing, mill stores, mill doctors, and if they were lucky - mill schools, and even baseball teams. It was taken for granted as children had worked on the farm; they would work in the factory to help support the family. A Huntsville newspaper boasted, "Huntsville Cotton Mill employed 100 boys and girls who would otherwise be out of employment."

Moreover Hine felt that child labor was "making human junk," and continued a vicious circle. "Child labor, illiteracy, industrial inefficiency, low wages, long hours, low standard of living, bad housing, poor food, unemployment, intemperance, disease, poverty," over and over and over. Hine made three trips to Huntsville between 1910 and 1930 taking 30 pictures that are still available. Mill owners banned him from the factories, and he could not gain entrance. However he was able, to take pictures during shift changes and at individual homes. Although the photos were made in the wintertime, many of the children are wearing ragged and torn clothing, no jackets, and no shoes.

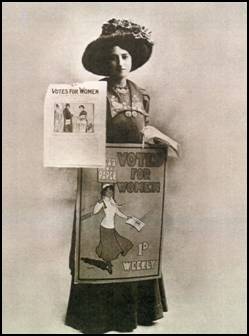

At the same time, overseas, the women's rights issue gathered attention as women organized. In the 1906 the London Daily Mail referred to the women in a new and insulting manner as Prime Minister Arthur J. Balfour received a deputation of the "Suffragettes." The newspaper label implied something not genuine, rather diminutive, or even to be ridiculed. The movement was something less than the real thing, as a small kitchen became a kitchenette. Thus suffragists became suffragettes, and the title stuck. In England the movement was thought so vile by many that, in 1913, George Bernard Shaw used them as an example, "That is the sort of thing that you vaguely lump into a cloud of abomination as Suffragettism."

In England the fight for women's rights had truly become a battle. In March of 1912 women with stones and hammers smashed windows in Regent St., Piccadilly, and Oxford Streets. The Prime Minister's house was attacked, and 120 women were arrested. As the actions intensified, bombs were ignited and more fires started. The violence continued to increase, and by 1914, thousands were in prison and many on hunger strikes. As the politicians tried to coup with the state of affairs, unacceptable solutions were tried. At first most of the striking women were forced-fed. Some of the women were allowed to starve, and then once they were too weak to protest, they were turned out into the streets.

In Alabama women were not idly sitting about. In 1892, the first woman's club had been formed in Decatur with Ellen Hildreth leading the way. Frances Griffin helped the women of Verbena to organize in 1892. Calera, Gadsden, and Tuskegee next formed statewide suffrage organizations. In Huntsville one of the most respected women in Alabama, Virginia Clay-Clopton, served as president of the local suffrage club. Sensing the bigger picture, Mrs. Hildreth formed a statewide organization that aligned with the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

After the 1901 Constitutional Convention disappointment, the suffrage movement barely survived in Alabama. Nevertheless, by 1910, the Selma Suffrage Association was organized with Miss Mary Partridge serving as president. Soon, a new generation of suffragettes offered fresh life to the movement, particularly in Birmingham. Mrs. W. L. Murdoch, Mrs. Solon Ruffner Jacobs, and Mrs. Oscar R. Hundley led the way as a state association was formed. Part of their plans called for missionary work in other parts of the state, and Miss Partridge made the first effort to form a political club in Montgomery. Annual conventions were held in Selma, Huntsville, Tuscaloosa, Gadsden, and Birmingham.

Pattie Ruffner Jacobs pursued reform causes and worked to abolish child labor and the convict lease system; she supported the Salvation Army and the Anti-Tuberculosis Association. (Mrs. Jacobs learned her organizational skills early. For instance, she circulated a petition which was eventually signed by 400 local women asking the city commissioners to sponsor a musical performance in city parks. The politicians denied her request. Mrs. Jacobs quickly realized if 400 voters had been on the petition instead of un-enfranchised women, her request would have been treated differently. Thus began her activities for women voting rights.) She worked to open an equal suffrage office in downtown Birmingham where clerks could rest, eat their lunches, use toilets, and read conveniently placed suffrage literature. Mollie Dowd also organized that city's first local of the National Women's Trade Union. Because a great deal of energy was spent by the women in club programs, training members, and raising money, the Birmingham group maintained a downtown office from 1913 to 1919.

The ladies sponsored free public lectures, distributed literature, and sponsored debates and essay contests. At the state and county fairs, wearing gaily-colored yellow sashes to call attention to their cause, they maintained booths and distributed handbills. They also spent time performing social services and humanitarian works, promoting good public relations for the cause. The ladies persuaded merchants in Birmingham to close their stores on Thursday at noon in the summer and before 10 o'clock on Saturday evenings. Gadsden women established a playground, and in Tuscaloosa women led story-telling hours for children. In Huntsville they presented each prisoner in the local jail with Thanksgiving dinner in 1916.

In Huntsville publishing suffrage sections in the newspaper raised additional money. Even the Mercury-Banner offered a supplement in the fall of 1913. Birmingham and Selma newspapers followed suit. Also, by 1915 there may have been as many as 14 suffrage columns in Alabama newspapers. But no newspaper endorsed this radical cause, and many ridiculed the women's efforts.

Meanwhile political leaders in the state such as Tom Heflin dismissed the women as "restless, dissatisfied products of unhappy homes." It was not that Rep. Heflin personally disliked women, but he referred to the suffragettes as "a few cranks trolling over the state." In 1914 he and Sen. Morris Sheppard of Texas introduced a joint resolution naming the 2nd Sunday in May as Mothers Day nation-wide and the resolution passed.

Church leaders (all men) just knew that suffragettes hardly represented the submissive woman of biblical injunction. Reverend H. C. Hurley, of the Jasper Baptist Church, produced a 25-page pamphlet suggesting that women should stay home and keep quiet.

Moreover, the opposition gathered steam. Adding insult to injury, prominent women began to organize and lead the Southern Anti-Suffrage Association. The opposition mobilized a formidable array of arguments - some related to states' rights. This should be a matter for the state legislature, not the U. S. Congress, and everyone knew traditional southern women had no desire to socialize with uncouth male politicians anyway.

Across the state, women continued their efforts. The Montgomery chapter of suffragettes formed in 1913 after Miss Partridge of Selma presented an inspiring speech, and Mrs. Sallie B. Powell became the first president.

One of Mobile's female leaders, Alva Erskine Smith, was a rarity even among the extraordinary women of her time. She had married William K. Vanderbilt, grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt, and the couple moved to New York City. There the new Mrs. Vanderbilt found that "society," or Mrs. William Astor, did not accept her. Mrs. Vanderbilt then built a three million dollar mansion on 5th Avenue and invited her neighbors. (Mrs. Astor did not come to call.) Alva's next social festivity was a masked ball for 1200 of her nearest and dearest friends. In order to obtain a ticket, Mrs. Astor did make an afternoon call at the mansion, and she was invited to the gala.

Later after her daughter, Consuelo, married the Duke of Marlborough, Alva Vanderbilt divorced her husband and married Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont. Comfortable with both her wealth and newfound position in society, Mrs. Belmont invited English suffragist Christabel Pankhurst for a speaking tour in the United States in 1914. Mrs. Belmont and other women wrote a suffragist operetta with Elsa Maxwell and staged it at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in 1916. Mrs. Belmont was likely the originator of the phrase, "Pray to God; She will help you."

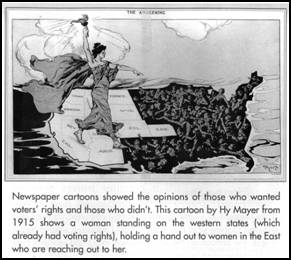

Nationally, the suffrage issue attracted much interest and intense feelings. In 1915 poet, Alice Duer Miller, wrote a column for the New York Tribune. Here she gave full vent to the emotions of many women. For instance lines from one of her poems asked the rhetorical question from her son, "Are women people?" The answer from the lad's mother, "No my son, criminals, lunatics and women are not people."

In Birmingham, Alabama efforts became quite sophisticated for the times. As the legislative session prepared to meet in 1915, time became of the essence. Bossie Hundley prepared a file on each legislator and his position on the movement. This master file contained a picture and available news stories on each representative. Mrs. Hundley prepared a survey, a short list of questions for each representative, and a volunteer was assigned to interview each delegate. These questionnaires included the man's occupation, religion, politics, if he was a preacher, married, a Civil War veteran, and his views on women's suffrage - in favor or opposed and if opposed why. Some of the replies were very telling. For instance:

Benjamin F. Ellis of Orrville spoke for many men, "I think it will ruin the women. Their place is in the home." His female interviewer noted that he was "an elderly man, of the old school and violently and unreasonably prejudicial."

A.M. Tunstall, Greensboro, fervently led the opposition. Mr. Y. L. Burton, of LaFayette, turned the question and asked Mrs. Hundley why women desired the ballot, a surprising issue to him. He thought women occupied, socially and otherwise, a more enviable position, in the South especially than they enjoy anywhere on the face of the earth.

Huntsville's David A. Grayson noted in a long hand-written reply,

"If I thought that women entering politics (and that is all it would be) would make them more attractive, more modest, more retiring, more congenial, or illuminate that halo, if reference and respect that we feel when in their presence, and I thought they would make better citizens, better women, better mothers, better sisters, better wives, better church members, and if I thought it would add to the sum of happiness of …I repeat if I believed all these things, or even half of them, I would vote for equal suffrage, yes, I would fight for it. But I believe it would have the very opposite effect." For "the government is the best government that has the happiest homes."

In answer to the question "Why opposed," his female interviewer said, "He doesn't know himself."

N. W. Scott, a real estate broker from Ensley, personally supported women voting, but he didn't think the majority of people who elected him were - of course his electorate was all men. Even H. H. Snell, President of the Men's League for Women's Suffrage, said he could only vote his conscience.

John A. Darden, Goodwater, added an element that many considered, but few said aloud except to friends. He was opposed to statewide suffrage, principally because of the possible Negro women voters.

An interviewer spoke to John W. Lapsley, he was young and impressionable, but unfortunately for the cause, "He thinks it was not in the Divine plan of salvation." (Who could argue with God?) Ernest Jones of Clio surmised, "I heartily concur with you that it is proper to hear the voice of the people." But how would he vote? Jones was known to be the most violent and active anti-suffrage person in Barbour County. Mr. Ira. B. Thompson perceived his constituency of Baldwin County 10 - 1 against the women. He smugly said, "I do not wish to criticize the move, but if women will take it down to reasoning with me, I am sure that I will convince her against it if she can accept a reasonable argument but the greatest drawback to a matter of that kind, they are too sweet and angelic-like to reason."

Even Helen Keller of Tuscumbia rebelled against her close-knit Southern society. Besides being blind, deaf, and mute, when she spoke out against injustice, politically powerful leaders belittled her comments as though they came from an inferior being, attributing her with still another handicap. Keller donated money to the NAACP years before the civil rights movement. She also was a self-proclaimed socialist, an activist for people with disabilities, and a suffragist.

From her column in the newspaper the New York Call in 1913, her remarks give one consideration even today. She began her column:

"Many declare that the woman peril is at our door. I have no doubt that it is. Indeed, I suspect that it has already entered most households. Certainly a great number of men are facing it across the breakfast table. And no matter how deaf they pretend to be, they cannot help hearing it talk.

"Women insist on their 'divine rights,' 'immutable rights,' 'inalienable rights.' These phrases are not so sensible as one might wish. When one comes to think of it, there are no such things as divine, immutable or inalienable rights. Rights are things we get when we are strong enough to make good our claim to them. Men spent hundreds of years and did much hard fighting to get the rights they now call divine, immutable and inalienable. Today women are demanding rights that tomorrow nobody will be foolhardy enough to question.

"The dullest can see that a good many things are wrong with the world. It is old-fashioned, running into ruts. We lack intelligent direction and control. We are not getting the most out of our opportunities and advantages. We must make over the scheme of life, and new tools are needed for the work. Perhaps one of the chief reasons for the present chaotic condition of things is that the world has been trying to get along with only half of itself. Everywhere we see running to waste woman-force that should be utilized in making the world a more decent home for humanity…

"When women vote men will no longer be compelled to guess at their desires - and guess wrong. Women will be able to protect themselves from man-made laws that are antagonistic to their interests. Some persons like to imagine that man's chivalrous nature will constrain him act humanely toward women and protect her rights. Some men do protect some women. We demand that all women have the right to protect themselves and relieve man of this feudal responsibility…. The citizen with a vote is master of his own destiny."

Time appeared to be running out in Alabama. The revitalized suffragists opened campaign headquarters in January of 1915 in a part of the historic Grand Theater building in Montgomery. The women proposed a bill to have a constitutional amendment submitted to the voters in the next year.

The women campaigned actively to ensure an amendment to the state constitution to enfranchise women. Leaders campaigned throughout the state. Funds were raised at county and state fairs. Rep. J.H. Greene of Dallas County (remember that name) offered to introduce a measure in the House and H.H. Holmes of Baldwin County introduced a similar bill the state Senate. The women had a hearing at a joint session of the legislative committees. Patti Jacobs and Julia Tutwiler, the strongest speakers, argued both a change and the status quo at the same time, for the proposed amendment would not enfranchise black women, just as existing election laws barred black men from voting.

There was strong opposition to the amendment, from prominent people. Individual males might lend their support, but not one single influential male organization declared for equal voting rights. Nor did the Alabama Federation of Women's Clubs voice an opinion. Women teachers did not declare, and no church group supported the women. With great anticipation on the day of the House vote, women filled the balcony. A suffrage banner was displayed draped with yellow and black bunting. Many legislators were yellow flowers in their lapels.

The ladies still felt confident; after all, their bill was sponsored by J.H. Greene. To the dismay of the group, the sponsor of the measure, Mr. Greene, with no warning, reversed his position. Was this the Mr. Greene who had months earlier driven a group of women in an "engine" to a suffrage convention in Selma? Mr. Greene at that time told the ladies that he would aid them and he had introduced the bill. He said then the only types of man which opposed the extension of the franchise to women were, "That mistaken type which holds that woman with the vote would lose her place in the heart and mind of man, that type which represents the whisky politician." Mr. Greene declared he was glad he changed his mind because of certain utterances of Dr. Anna Howard Shaw who said that "womanhood should be independent of any man…" Mr. Greene had no apology to make for decision. In committee the bill was postponed and on the actual day of vote, Mr. Greene, the author of the bill, and the possessor of the deciding vote in a 6-6 tie, was not present.

One also must consider that a valid reason might have been, "To confer suffrage on women in the south would double the Negro problem by adding to it the more vicious and aggressive element of the race. For this reason I think it is far better to stay as we are."

An anonymous pamphlet appeared which suggested that most Alabama women did not want the vote. Although the measure received the major vote, the suffragettes did not obtain the necessary three-fifths majority. The Senate agreed and the resolution to bring the issue before the voters in 1916 was defeated.

Meanwhile, in Washington, D. C. hundreds of women were parading for suffrage rights, much to the embarrassment of President Wilson. Many of these women were arrested and sent to the district's work house in nearby Lorton, Virginia. This was an institution for criminals guilty of minor law violations. Adding insult to injury, they slept on the floor and some were force-fed, which came as quite a shock to the public when pictures of these events appeared in the papers.

However the urgency of the suffrage mission was set aside as women groups assisted in World War I efforts. Already organized, women's groups capably helped with draft registration, enlistment of women for volunteer home service, Liberty Bond Loan drives, and Red Cross projects. They offered free classes in practical subjects, such as stenography, nursing, telephone and telegraph operation, and automobile driving to help train women for better home service during the war.

In Decatur, the clubwomen were appalled at the government statistics during army registration. Alabama had the second highest rate of illiterate soldiers in the nation. (Thank goodness for Mississippi.) Furthermore 20% of the adults in this state could not read. Women's groups met in Montgomery to begin a campaign against illiteracy. (With the leadership of the women from Decatur like Mrs. Louis A. Niell, Clara Wyker, and Margaret Shelton, the Alabama Federation of Women's Clubs promised to fund this campaign.) Six teachers were hired to teach the young men at military camps in the state. Textbooks were printed and distributed. The Illiteracy Commission reported 6893 men of draft age were taught to read and write. The hard-working Decatur women were also instrumental in building the Benevolent Society Hospital there.

After the war President Wilson and Congress acknowledged that women's war work should be rewarded with recognition of their political equality. Wilson began to support woman suffrage in public addresses. A year later both the House and the Senate endorsed the proposed 19th Amendment to the Constitution.

As the country settled down in 1919, the U.S. Senate and House submitted the woman suffrage amendment to the states. For Alabama this was an ideal time. The state legislature was scheduled to reassemble on the 8th of July. The suffragettes were ready. They began this session with a ratification dinner in Birmingham. Prominent members of the legislature, Governor Kilby, and other major leaders were interviewed. The national association sent organizers to Alabama, and the nation watched as this vigorous campaign might lead to the first state passing the amendment.

Meanwhile, of course, the opposition was not sitting idly by. The Women's Anti-Ratification League of Alabama showed growing numbers led by Mrs. James S. Pinckard and Maria Bankhead Owen, daughter of Senator John H. Bankhead. Others opposed to enfranchisement by the Federal amendment joined this group, including J. Lister Hill. US Senators Oscar W. Underwood and John H. Bankhead viewed the amendment as a threat to states' rights. Clarke County politician, John Simpson Graham, noted in 1919 that women's workweek was already reduced to 56 hours - a little over nine hours a day, with Sunday off. "Men had prohibited night work, secured women's property rights, and limited child labor. Women have gotten everything they have coming to them…and they should be satisfied."

Representative Tom Heflin felt giving women the vote was a threat to family life. The newly formed Alabama Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage campaigned through the South at this very crucial time. The anti-suffragists of Alabama won absolute victory.

On July 8, 1919 the legislature reassembled and Representative J. Lee Long of Butler County introduced a resolution to reject the proposed federal amendment. This not only would secure defeat of a ratification resolution, but would also secure adoption of another resolution, which specifically rejected the amendment. Thirteen rejections were needed to defeat the action by the Federal government. Senator James B. Evins pleaded for their side that they not be forced "from the quietitude of our homes into the contaminating atmosphere of political struggle." After the voting it was quite evident who had won and who had lost. The voters of Alabama (all male) had rejected the 19th Amendment.

At the same time, voters across the country took action for female suffrage. When 35 of the necessary 36 states ratified the amendment, the battle came to Nashville, Tennessee. (One concerned matron sent a desperate plea to the Tennessee legislature not to ratify the suffrage amendment. She regretted that suffrage had already come to the west coast because "there has been a large increase in immorality, divorce and murder in California. Women's suffrage has made cowards and puppets of men; it has coarsened and cheapened women.")

The final vote was scheduled for August 18, 1920, and it appeared the vote would be tied at 48 to 48. Harry Burn, 24, a young legislator, had previously voted with the anti-suffrage forces, but his mother urged him to vote for the rights of women. She sent a telegram, "Dear Son: Hurrah, and vote for suffrage!" And on that day, as all good sons could, he did what his mother told him to do! Tennessee became the deciding state to ratify. The governor sent the required notification of the ratification to Washington, D.C., and on August 26, 1920 the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution became law.

In Alabama, Governor Kilby called a special session of the state legislature to ratify the already ratified. As a side effect, polling places, long notorious for card playing, drinking, and raucous behavior, was forced to become more sanitary and decorous. Men still dominated society, but women had taken a major step toward equality. Women voted in the 1920 elections.

Progressive female reformers could point with pride to the passage of the 18th Amendment (prohibition) and the 19th Amendment (women's suffrage) as major accomplishments. Alabama women were there.

The material for this monograph has generally come from these following sources: