"I hear the sound of fife and drum the other side of the village, and am reminded that it is the May Training. Some thirty young men are marching in two straight sections, with each… a bright red stripe down the legs of his pantaloons, and at their head march two [men] with white stripes down their pants, one beating a drum, the other blowing a fife."

Perhaps the early militia men of what would become Madison County, Alabama were not as gaily clad, but surely they were as attentive to their duty.

The history of a civilian militia is a long one - by necessity. In England, musters became a periodic assessment of the availability of local men to provide defense when needed, thus to pass muster, or to be sufficient. This concept became critical in early America with the seemingly never-ending confrontations against enemies - Native Americans, the French, Spanish, British, and occasional roaming gangs of outlaws.

When called upon during the few calm periods, the early American militiamen viewed militia camp as a temporary duty, in opposition to the English who regarded the colonial militiamen only as substitute manual laborers to build and maintain roads and bridges, cut firewood, and other distasteful assignments, traditionally done in Europe by peasants. [1]Whisker, James Biser, American Colonial Militia (Lewiston, England: Edwin Mellen Press, 1997), Vol. 1: 72, 73. In the United States, the local militiamen had already proved vital to success in the French and Indian Wars.

During the Revolutionary War, as they felt assured of victory, the British planned to disarm the Americans. Then, by repealing the Militia Laws, all arms would be taken away from the Colonials and no foundry or manufactory of arms would be allowed; there would be no gunpowder or war-like stores, nor lead or arms imported without license. [2]Whisker, 1: 7.

Among other engagements, however, the southern militia aided to suppress loyalist activities and supported the regular army. They participated in the Battle of Green Springs against Cornwallis and the siege of Yorktown. Moreover, the patriot militia of the Over-the-Mountain men provided a particularly pivotal moment in the southern campaign. They soundly defeated the loyalists' militia at the battle at Kings Mountain, which certainly turned the tide of the War.

The Revolutionary War clearly reinforced the need for the militia on all fronts, and the Second Continental Congress codified regulations for it. The full-time regular army was created, but because it was always short on manpower, the militia provided short-term support to the regulars in the field. (Of course Loyalist sympathizers were excluded even if they had formerly held positions in their militias.)

The men, and boys, continued to prepare to meet any threat. The Militia Act of 1792 provided, in part:

"That each and every free able-bodied white male citizen of the respective States, resident therein, who is or shall be of age of eighteen years, and under the age of forty-five years (except as is herein after excepted) shall severally and respectively be enrolled in the militia."

Furthermore, when called upon, the citizen soldier should be at the ready to appear with his own equipment: a good musket or rifle, two spare flints, a bayonet, and a knapsack. There were the usual exceptions: high government officials, ministers, ferrymen, mail handlers and justices of the peace were exempt. [3]Owen, Thomas McAdory. History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography (Spartanburg, SC, 1978, Reprint Co.), 2, 987-9. The Alabama Constitution written in 1819, among other liberal clauses allowed those who conscientiously objected to bearing arms to pay a fee in lieu of serving.

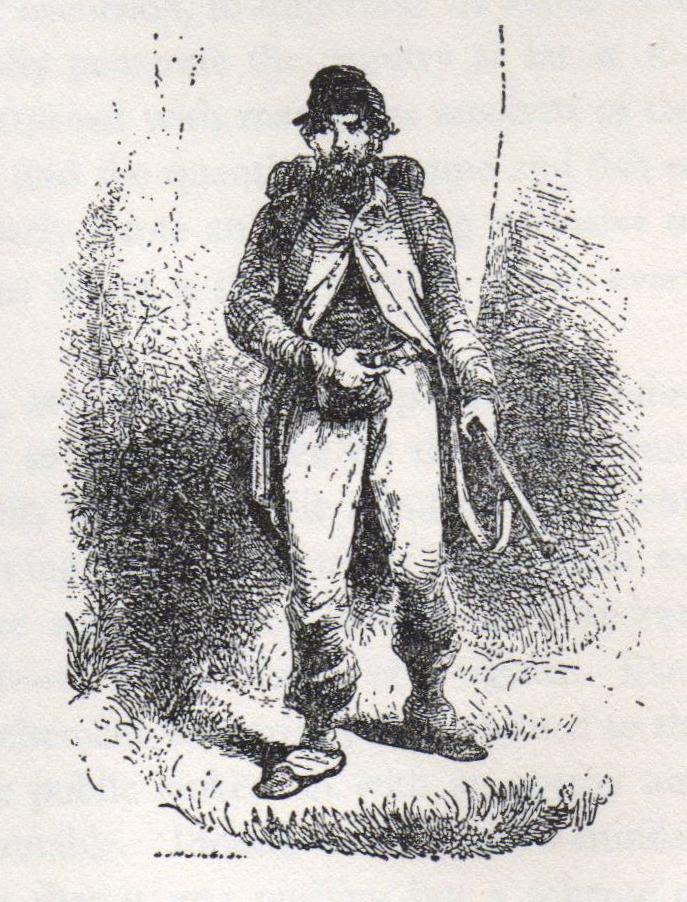

This militia formed into brigades, regiments, battalions, and companies. Fines were assessed according to rank, for those who appeared without proper uniforms and equipment. A colonel led the Regiment, each Battalion had one major, and each company had a captain, lieutenants and corporals. Most legislatures allowed the volunteer company to elect its own officers, write by-laws, select its own name, and design its uniform. On the frontier most uniforms were likely to be hastily donned, and were perhaps even ill-fitting, linsey-woolsey and not particularly clean.

The area between the Atlantic coast and the eastern side of the Appalachian Mountains seemingly settled quietly after those early conflicts. However in the vast spaces farther inland, beyond the once forbidden mountains among the sparse settlements, the need for readiness remained essential.

Presenting a showy display was never an aim of the militia on frontier lands as they became available. The menfolk and their families who immigrated to the frontier understood the need for protection. These men at the beginning of the 19th century had fought, or seen their fathers and heard their grandfathers' tales about the life and death struggle with the Native Americans. Indian raids continued to lead to loss of possessions and land, burning, scalping, and death. As a result most settlers knew how to shoot firearms, and even though their horses might not be the fastest, the men all showed good horsemanship. Settlers remained vigilant at their farmhouses or at outposts as they waited to enter the newly opened territories of the old southwest.

By 1805, John Hunt had begun his log cabin near the Big Spring and other pioneers followed - all illegal intruders, of course. Countless (at least as many as six or seven hundred enumerated settlers) decided not to wait, and entered unlawfully into the Indian territories of what would become Madison County, Mississippi Territory. Here they planted crops, shelters, and themselves. What did not always grow quickly, however, was law and order. Occasionally, the anonymous Captain Slick and his men took the law into their own hands as a speedy solution. Slick's committee might first issue a warning to the miscreant simply to leave town, perhaps adding a thrashing with a hickory rod to add emphasis. If forced by the committee to leave, the miscreant was lucky only to be "fed a supper of Blue plums" from a double barrel shotgun. Apparently Captain Slick's law "purified the moral atmosphere." [4]Taylor, Judge Thomas Jones. History of Madison County and Incidentally of North Alabama, 1732-1840. eds. W. Stanley and Addie S. Hoole. (University, AL: Confederate Publish. Co.,1976), 28.

Nevertheless, the need for real order became pressing. In 1808 President Jefferson appealed to the governor of the Territory, Robert Williams, to select civil officers to provide law and order. Madison became a county on December 13, 1809, and later that month, Stephen Neal was appointed Sheriff and Justice of the Peace. Thomas Freeman was also appointed to serve as a Justice of the Peace and to take a census of the squatters. He became the official surveyor, and subsequently served as registrar at the sales held in Nashville - all in preparation for the coming land boom. Perhaps to no one's surprise, Thomas Freeman became the largest purchaser - 22 sections, over 14,000 acres of Madison County land.

As the squatters continued to arrive, the federal government built Fort Hampton on the Elk River to secure the Indian property in 1809-1810. (This was one of the few acts by the government to protect Indian lands.) The crops and houses of the 93 "intruder" families were burned, and the displaced settlers crowded into Madison County. And still they came.

The way west and south had been long and arduous; no one wanted to make the return trip to their former homes. Those who arrived most likely came down the "Great South" Indian trail from near Winchester, Tennessee before continuing south to settle along the way. The wagons, carts, riders and walkers found, to no surprise, roadways that weren't roads, wagon tracks that disappeared into swamps, and raging creeks and rivers with no bridges. Of course it was always necessary to watch for possible hostile Indians. The new countryside and Big Spring were a welcome sight.

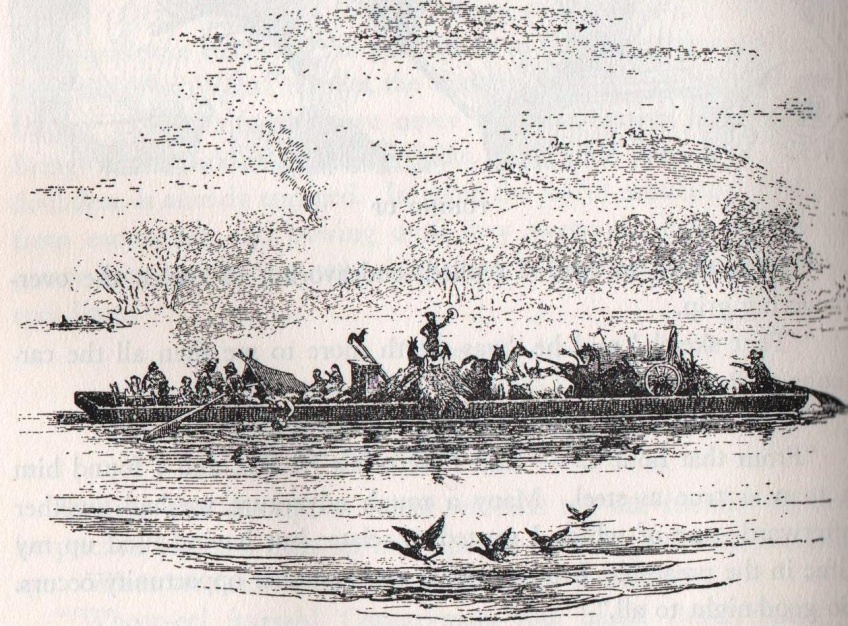

Old Man Ditto's Landing was also a welcome site for those who descended the Tennessee River from Ross's Landing, later Chattanooga. Traders had long used the river as the Indians had, but now the river opened the way to the new lands for settlement. As the pioneers successfully maneuvered their rafts or keelboats through 30 miles of the "The Suck," where the river narrowed to half its width, they still intently watched the Cumberland Mountain bluffs above them. From there hostile Indians could fire down freely at passing boats. Now all that the settlers faced farther downstream were boat wrecks, accidental drowning, soggy food, wet powder, sand bars, shallow dips, and snag-infested rocky shoals.

With this continued influx of people who required law and order in the eastern lands of the territory, Governor Williams made the initial militia assignments. (The Governor was of course, Commander-in-Chief.) He appointed Nicholas Perkins to head the newly formed Mississippi 7th Regiment, and William H. Winston, Adjutant. Stephen Neal was appointed 1st Major; Alexander Gilbreath became 2nd Major. The first Madison County-wide muster was held on October 29, 1810. To add his formal approval, the new Governor, David Holmes, attended the grand ceremonies on the muster field, most likely on the flats below the Big Spring. [5]Record, James. A Dream Come True (Huntsville, AL.: Hicklin Printing, 1970),1: 33-36.

These military appointees were extraordinary men. Well educated, they seemed driven to take advantage of what lay before them - land, progress, and, perhaps with luck, wealth.

Commandant and Lt. Colonel Nicholas Perkins, trained as a lawyer, had already served his country well. He was a member of the Mississippi Territory House of Representatives for Washington County in 1802 and Speaker of the House in 1803. In February 1807, while serving as land registrar in Washington County, Perkins thought he recognized two mysterious men traveling after dark with their faces concealed. He rode for the sheriff who quickly enlisted more help from the nearby fort. These fugitives from justice, Major Robert Ashley and former Vice President Aaron Burr, were arrested by troops from Fort Stoddert and escorted north for federal trial in Richmond. Soon after, Perkins was appointed Attorney General of the Mississippi Territory, eastern district, for 1807-09. Perkins did not purchase land in Madison County sales, however, and moved to Tennessee. During the War of 1812, he served as a Colonel of the 1st Regiment of Western Tennessee, and he saw action in the campaigns of 1814 under General Jackson. He led sixty-day volunteers who enlisted to fill the depleted ranks of Jackson's rapidly dwindling army, experiencing some of the fiercest action in 1814. Nicholas Perkins died in Franklin, Tennessee, "one of our most distinguished citizens" in 1848. [6]Valley Leaves Special Edition'' (Huntsville, AL: Tennessee Valley Genealogical Society, 1969), 21; Abstracted by Jonathan Kennon Thompson Smith. ''Death Notices from Western Weekly Review. (Franklin, TN. 2004), 289.

First Major Stephen Neal was considered "an active and intelligent man," and he certainly his talents on many occasions. Among other dealings, Neal bought for $500 a town lot facing the Square on Commercial Row and sold it to C. C. Clay and six others for $8000. By the time Neal married Frances Green in 1818, he was well able to support her and their family. While he continued to serve as sheriff until 1822, during these years he took advantage of his knowledge to purchase and sell over 2256 acres of land in the county. Sheriff Neal died in 1839, age 66 (Mrs. Neal, thought to be the oldest living resident in Huntsville at that time, died at the age of 96 in 1883). [7]Taylor, 44; Pauline Jones Gandrud. Marriage, Death and Legal Notices from Early Alabama Newspapers, 1819-1893'' (Easley, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1981), 280. The sheriff is not always the most popular person in town. In an election for delegates to the Convention of 1819, Stephen Neal came in last place. Neal garnered 63 votes; among others running James Titus had 416 votes and the winner, C.C. Clay, won with 1683 votes. (''Alabama Republican, May 8, 1819.)

Second Major Alexander Gilbreath, one of the enumerated squatters waiting to enter the county legally, along with five other men, were selected to serve as Commissioners, establishing locations for public buildings in Huntsville. These men were given authority to purchase land to be laid out in half-acre lots, three of which were to be reserved for public buildings. (The remaining lots would be sold to defray the expense of erecting public buildings - courthouse, jail, and market.) Gilbreath maintained a store near the spring and may have been the first merchant in town. He was later in partnership with James White, for whom Whitesburg was named. [8]Taylor, 37; Eden of the South. ed. Ranee' G. Pruitt (Huntsville, Huntsville-Madison County Public Library, 2005), 3.

Perhaps it was already becoming too crowded in Madison County. Gilbreath purchased only 39 acres in the local land sales before he moved to the Red Hill area of what would become Marshall County. There he married Polly Brown, half-sister of Catherine Brown. Catherine, a Cherokee educated at Brainerd, Tennessee, became a legendary teacher. (The sisters later taught Cherokee girls at Creek Path School.) In Marshall County, Gilbreath purchased over 360 acres and by 1840 owned 13 slaves. Gilbreath died in 1860 at the age of 80 and was interred in the family cemetery. His wife, Polly, was not buried there with him, however. At the time of the Cherokee Indian Removal, Polly made the trek to Oklahoma with many others. Alexander, according to family stories, was unable to join them because of his great size, too large for a horse or the carriage, and he remained in Marshall County. [9]Cowart, Margaret Matthews. Old Land Records of Marshall County, Alabama (Huntsville: AL M.M. Cowart, 1988), 81,84, 85, 345; Conversation with Larry Smith, Feb. 6, 2012, regarding family stories of descendants Sonny and Margie Lewis as told to Smith.

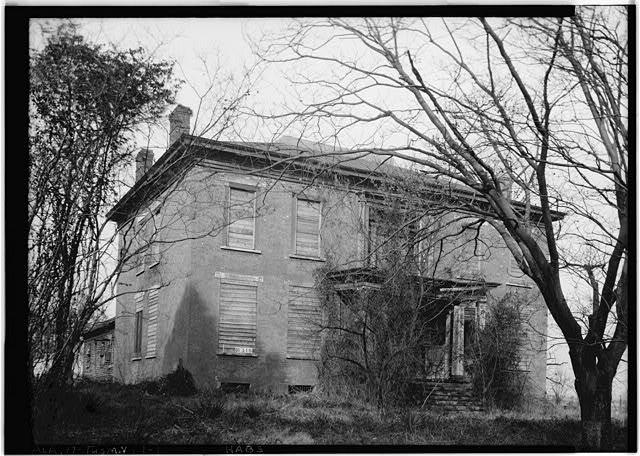

Adjutant William H. Winston migrated from Buckingham County, Virginia. Here, Winston was also appointed Clerk of the County Court of Madison County in 1809. Citizens then elected Winston to the Mississippi Territory House of Representatives in 1810 and again for 1815-17. During these years Winston bought and sold over 2248 acres in Madison County before he and his wife Mary (Cooper) Winston moved on to Tuscumbia. [10]History of Early Settlement: Madison County before Statehood, 1808-1819 (Huntsville, AL: Huntsville-Madison County Historical Society, 2008), 9, 43. This house, pictured in a Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) photograph, was begun in 1824 and the couple completed it nine years later. (The city of Tuscumbia has since purchased and restored their home.) Their son, John Anthony Winston, born in Madison County became the 15th governor, the first born within the state. [11]HABS, Colbert Co. southernspiritguide.blogspot.com

The eight militia companies, established in 1810, were led by Captains John Grayson, Joseph Acklen, James Titus, Allen C. Thompson, William Wyatt, William Howson, James Neely, and Henry Cox. (Martin Beatty declined a captaincy.) These officers led the militia to provide defense and also a setting to administer public affairs. Throughout the county, under the leadership of the captains, court days and election notices were posted, taxes were assessed and collected, and of course politics were discussed, or argued, as the case might be.

John Clan Grayson, a surveyor himself, joined Thomas Freeman, to make the assessment that was so necessary for legal land sales. Grayson's interest was personal because he was also one of the squatters waiting to gain lawful entry. To begin their task Freeman and Grayson went to John Hunt's cabin to discuss the task ahead. The men and their team then began measuring from Chickasaw (Hobbs) Island north to establish the base lines. Certainly Grayson had a fine opportunity to see and judge the land of Madison County. In early spring of 1806, Grayson's family arrived in a train of covered wagons to settle east of the mountains. There were seven children (six more would follow), a governess, two slaves and other workers. Mrs. Grayson and the children stayed in the covered wagons while the men constructed a four-room house with a dog trot. Grayson eventually bought 640 acres. Adding to his militia duties, John Grayson was later appointed Justice of the Peace. He died in 1826 at the age of 56; his wife died in 1838. [12]Taylor, 72; William Sibley. Welcome to Big Cove: The History of Big Cove, 1807-2000'' (Brownsboro, AL., W. Sibley, 2003), 57, 10; ''Heritage of Madison County, Alabama. (Clanton, AL., Heritage Publishing, 1998), 215, 216.

Joseph Acklen was also part of the 1809 "squatter" census with his household of four. In 1810 Acklen was appointed to be an Estate Appraiser, a significant post and an essential role in times of debt or death. His experience and leadership led to an assignment later as Captain of the 7th Regiment during the War of 1812. Although he paid poll taxes from 1810 through 1815 on 160 acres purchased in what would be southwest Huntsville, by 1814 he had moved into the Elk River area of Tennessee, where he married in 1819. Joseph Acklen died in Winchester, Franklin County, Tennessee in 1841. [13]Franklin County, Tennessee Land Records'', comp. Jeanna Gallagher; genealogytrails.com on 3/31/12; ''Tennessee Wills, 193-194.

Henry Cox purchased 480 acres in the Huntsville area and in 1816 married a local woman, Jane McClain. There is little information about his stay here except that he held 960 acres near Indian Creek and had 22 slaves. The number of slaves and the amount of acreage varied, but he paid taxes from 1810 through 1815. Cox also served as the paymaster for the 7th Regiment from 1808-1817. [14]Valley Leaves, Vol. 4, #4, 2-9.

Although William Howson purchased 400 acres southwest of Huntsville, he, his family of six, and two slaves, probably lived in town where he served as county jailor (at least in the years 1831 and 1832). Although there were other settlers with that surname paying taxes during the years 1811-1819, those names were not on census and county records later. Others named Howson, paying taxes between 1811 and 1819, were Sally, Thomas, and John. [15]1830 Federal Census: Acts of General Assembly of the Legislature of Alabama, 11.

Among other settlers in the area was the extended Drake family. In 1807 James Drake, a brother, and brother-in-law, James Neely, came down the Tennessee River on a flat-bottomed boat to Ditto's Landing. They settled, as squatters, near John Grayson. Members of the Drake family led by Capt. John Drake, a Revolutionary War veteran, and five of his sons and their families followed in 1810 and 1811 to purchase land. (Reflecting the close-knit ties of migrations, of the 10 Drake children, six of them had married Neelys in Virginia.) Captain James Neely bought 159 acres in the southeast but settled and built a home on Holmes Street in town. He was a pump maker, and, for six years, supervised the Huntsville water works. In addition to his duties with the militia, he was appointed as one of the road overseers in 1810. [16]Sibley, 78; Taylor 113; 296.

James Titus came down from Fort Nashborough, Tennessee where his family had relocated in the 1780s. After his first wife died, Titus married Nancy Holmes in 1808 and they prepared to move south. His land holdings, over 500 acres, were in the Oakwood area. Holding credentials as captain in the new militia in 1810, he also became a member of the Mississippi Territory legislature from Madison County and served from 1812-1817.

Governor Holmes convened the Legislature, and members served from their home areas on the Mississippi Territory Assembly in 1814. Three men were appointed to the Council, similar to the upper house or Senate. Robert Beatty of Madison County resigned; Joseph Carson from Washington County died; and James Titus of Madison County remained to serve. Not singularly deterred, Titus rose to the occasion and elected himself president of the Council. He appointed doorkeepers, conducted the proceedings with appropriate formality, called the Council to order, answered the roll call, voted on bills, moved for adjournment, voted on his motion, declared the Council adjourned, and no one disagreed.

Duty called again, and James Titus and his son, Andrew Jackson Titus, participated in the removal of the Choctaws in 1831. During this time they lingered in the Red River area of Texas and decided to resettle there. Titus and his son were active in acquiring statehood for Texas, and Titus County is named for the younger man. James Titus was buried in a family cemetery in Savannah, Texas. In the same cemetery, buried only a few feet away, is another former Huntsvillian, Robert Beatty, who earlier had declined to serve in the Territorial Council with Titus. [17]Taylor, 12; William H. Brantley. Three Capitals (University, AL.: Univ. of Alabama Press, 1947), 24, 225; Taylor 109.

Captain Allen C. Thompson did not purchase land in the early sales of Madison County. however, he and his family appeared in the 1820 census of Franklin County, Alabama. His wife, Charlotte, died near Florence, at age 64, in 1835. In 1837 Thompson married Elizabeth M. Fox, widow of John Fox, of Limestone County. Captain Thompson died not long afterwards and his widow became the head of the household of five, living next door to her son Allen Thompson. [18]Rev. Silas Emmett Lucas, Jr. ed. Obituaries from Early Tennessee Newspapers, 1794-1851 (Easley, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1978), 366; Gandrud, 324; 1840 Federal Census.

As the small communities within the county were becoming organized, news of the disaster on August 30, 1813 at Fort Mims in southern Alabama raced northward. At least 250 settlers had been killed at the fort and 100 more were captured by the Creek Indians. This was the worst massacre in the history of America, and it flamed further momentum to eliminate the Indians. Fears quickly followed that a large body of warriors was on its way north. In panic, alarmed citizens of Madison County fled toward Nashville's fort over 100 miles away. Just a few years later, Anne Royall, that intrepid traveler, reported in her letters about the disarray as told to her. Apparently about a thousand people were on the road to Nashville that day, and only two families remained behind. "These barricaded the door of the Court house which served them for a fort; and old Captain Wyatt…assumed the command. He had but two guns, but being well charged with whiskey and courage, he kept up a constant fire…." It was a false alarm, thank goodness. Perhaps exhausted by his efforts, the brave "old" defender, Capt. William Wyatt died just two years later in 1815, aged 56 years. His steadfast partner, Susannah E. (Jones) Wyatt lived until 1836. Unfortunately the other couple defending the town that day is unknown to history. [19]Anne Newport Royal. Ed. and annotated by Lucille Griffith, Letters from Alabama 1817-1822'' (University, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1969), 244; ''Valley Leaves, Vol. 17, #2 (June 1983), 187.

Few of these settlers came alone. A link that seems to run through the early years gives one pause to consider the possible connections between other local men sharing those first militia leaders' surnames - Louis, Joel, and John Winston; Peter and Constantine Perkins; Henry Gilbreath; John Neal; John, Sam, Alexander, and William Acklen; John, Ben, George, William, and Peyton Cox; Jerome, Ambrose, Benjamin, and others named Grayson; John Howson; John, Andrew and Eli Neely; George and Ebenezer Titus; John and Peyton Wyatt. Their stories remain for others to uncover.

As these officers and militia offered protection, the rougher days of early frontier life appeared to have passed. A newer class of settlers arrived with money in their pocketbooks ready to spend; wealthy entrepreneurs arrived with their families. Settlers like the developers LeRoy Pope and Gen. John Brahan came; doctors Thomas Fearn and David Moore; merchants James White and the Andrews brothers; lawyers C. C. Clay and John Williams Walker; newspapermen Phillip Woodson and John Boardman. These names remain a part of Huntsville lore.

Less remembered, perhaps, were the likes of Allen Cooper and John Bunch who offered hospitality at their taverns. Ebenezer Darby was a shoe and boot maker; Thomas Collins opened a bakery; the brothers Cain were watch-makers and gold and silversmiths; Richard Champion worked as a hatter. As the settlement continued to grow in size and safety, working-class settlers found jobs to fill the needs of blacksmith, tanner, brick-maker, and mason. More settlers with empty pockets continued to arrive with dreams and aspirations.

Countless and mostly nameless slaves arrived - men, women and children, many in chains - to work for and serve masters. Scores were separated from and left behind their own families. The same militia which protected the frontier also patrolled for runaway slaves, or any who might be out after hours without a pass.

The militia arrangement also allowed a system of convenient political units, or beats. Generally, one Justice of the Peace and one Constable were elected from each military beat, later to be called precincts. The Justice of the Peace, or Magistrate, held great power with jurisdiction over minor criminal offenses, performed marriage ceremonies, took legal depositions and arbitrated minor disputes; among other things. The constable held less power than the County Sheriff because his jurisdiction was confined to the military district or precinct from which he was elected. So the muster grounds became the meeting place where justices, constables, overseers of the poor, and militia officers were appointed or elected from the community. [20]Sibley, 27, 28; Valley Leaves, Special Edition, 59, 60.

Law required an announcement of a muster in the newspapers, four times a year under a notice written ATTENTION. Fines were assessed if muster was missed. Locations were chosen conveniently at sites like the town square, old Blue Spring Camp Ground, John Connolly's Green Bottom Inn, over the mountains at Henry Brazelton's in Big Cove or any likely field big enough to hold the crowd.

Muster day and militia practice, like later political barbecues, elections, and religious camp meetings, offered a relief from the monotonous life of isolation so common at the time. All citizens looked forward to patriotic celebrations, holiday commemorations as the 4th of July, or Washington's birthday, but muster day came four times a year! Everyone gathered, and of course poor whites, free blacks and slaves could be onlookers to the excitement, too. There would be much to behold.

At the meeting grounds and after inspection, absences were noted for later court martial or fines. The disciplined drills and maneuvers followed a standard manual of the day and ended with the formal review by the highest ranking officer. After the drill, the men were ordered to be at ease. Now came the time to relax, socialize and perhaps for manly challenges or even settling old scores.

A later City Directory acknowledged those earlier days:

Court days and muster day were the occasions upon which the people usually congregated en masse. Then it was that fist-fights and free fights were usually indulged in to the usual end of bruised faces and bodies, and a too ready access to stones often rendered these encounters more serious than the feelings of animosity really felt, would have otherwise dictated… A resort to the pistol or bowie-knife at that time was of rare occurrence, for that early day, when upon a man's physical prowess depended mainly his coveted position in the social circle or as a citizen, a test of his manhood.

Men settled the "ills they had suffered by a resort to natural defenses, than by the use of pistol or knife…." The reader almost felt with regret those proud days long gone. [21]Williams Huntsville City Directory, City Guide and Business Mirror, vol. 1, 1859 (Huntsville, AL: Coltart, 1859), rep. Strode, 1972, 10, 11.

No matter about the casual violence of the day. Of course a crowd always gathered of family, friends and on-lookers, black, and white, young and old. Spectators also included vendors, fiddlers, and perhaps a few gamblers. The women had prepared food, and there was enough for everyone to enjoy and linger about the entire day. Many women, with the tradition handed down by their mothers, prepared and sold gingerbread and other confections. Likewise, their men enjoyed the company of the others and shared an evening of drinking. Some few of the men, perhaps with muddled brains and unsteady feet, dragged themselves home at the end of the day. The prudent wife led the way, perchance with the jingle of a few new coins in hand, at the least with a head full of news from family and friends. Tired children slept in the back of the wagon if they were lucky, and there would be little back sass from that quarter. Thus another Muster Day would pass into the history of the county - with the eager anticipation of the next one to come.

All was not peaceful peaceful: the massacre at Fort Mims in the south on August 30, 1813 threatened every settlement. It was past the time for a strong defense but became a time for forceful action. General Andrew Jackson issued an order on September 24th to his "Brave Tennesseans" to rendezvous at Fayetteville for immediate duty against the Creeks…We must hasten to the frontier "or we will find it drenched in the blood of our fellow-citizens." [22]Remini, Robert V. Andrew Jackson and His Indian Wars (NY: Penguin, 2001), 61.

If there was any doubt of the threat, the militia continued to be called to action. "Brave Tennesseans! …Your frontier is threatened with invasion by the savage foe! Already do they advance towards your frontier, with their scalping knives unsheathed, to butcher your wives and children, and your helpless babes." [23]Cited in Hudson, Angela Pulley, Creek Paths and Federal Roads'' (Chapel Hill, NC: Univ. North Carolina, 2010), 113 from "General Orders," ''Louisiana Gazette for the Country, Oct. 13, 1813.

Fearing an imminent attack on Huntsville, on October 11th General Jackson's volunteers and militia men, 4000 strong, marched the 32 miles from Fayetteville, Tennessee to Huntsville in five hours. (Among the more notable men were Colonel John Coffee, David Crocket and Sam Houston.) Huntsville was not attacked but remained a staging area for supplies leading to the Battle at Horseshoe Bend. The Tennessee militia men clustered around Beaty's Spring (now Brahan's Spring) to be joined by the brave volunteers of Madison County. Armed and trained, the militia men of Madison County, Mississippi Territory would meet the call.