And the Laws of God"

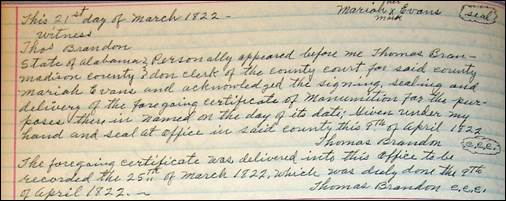

Thus began the required legal "free" papers for Richard Evans filed at the courthouse in Madison County, Alabama in 1820, as Mariah Evans, a free woman of color, emancipated her husband, Richard.[1]Mariah Evans, free woman of color emancipated her husband, Richard Evans. Madison County, Alabama Deed Book I, 48; Deed L, 237. (Hereafter cited as Deed Book.) He too now would have the status of freedom from bondage, never citizenship, but freedom.

Wedged somewhere in the Madison County past lived a small cluster of people with little apparent standing. Mistrusted habitually by white citizens and often resented by black slaves, they were in effect "slaves without masters."[2]Ira Berlin used this for his title, Slaves without Masters: The Free Negro in the Antebellum South. (NY: Random House, 1974) to develop his respected and well-researched book. These free people of color lived a precarious balance between not offending whites or blacks from whom their daily survival depended. Although there is little to define their lives, some individuals and family groups succeeded, and some did unpredictably well among their neighbors.

The purpose of this essay is to explore the number, circumstances, and accomplishments of free persons of color in Madison County, Alabama. Little was written during the times about their lives other than a few legal papers. But, what were the restrictions they lived under? What privileges, as free people, might they have? At the least different from their brethren, the slaves, these free people of color, unlike Senator Clay's "boy" Matt, could have an identify and would have a surname.

As a learning experience for the author, this discussion will begin with definitions and exploration of the obstacles and legal restrictions of the time, including an attempt to understand a part of their life that has at least been recorded. Appendix I includes the Federal Census reports for 1820-1860. For notations and citations about Madison County individuals, see the text in Appendix III.

Some names will be in both sources. I offer sincere thanks for the suggestions and encouragement of Linda Allen, Donna Barlow, Abby and Donna Dunham, Jamie Hooks, Dian Long, Terry Lee, Kate Rohr, and of course, John Rankin. If one could make a dedication to such work it would be to Amy Butcher and Rachael A. Pauper.

A free person of color, as compared to a slave, was someone of full or partial African descent, not enslaved, a free Negro or of mixed race as mulatto. Manumission by owner or emancipation is the act of setting free or being set free from slavery. These free black people - men, women and children - were positioned somewhere between the slave population and the white citizenry. As slaves yearned for freedom, they may easily have resented the freed persons of color. Whites considered these unchained blacks to be a threat. Who might better stir the slaves to take action for freedom than a man already free? As a result this small, unwanted third caste became increasingly restricted. Eventually, Alabama, a Deep South state, attempted by legislative acts to control this small minority, and finally, force them to leave.

The laws regarding free people of color had always been a part of the legislative acts of the Southern states. In 1805 the fledgling Mississippi Territory, which included the area that would become Alabama, enacted within its code a law to allow emancipation. However, one might consider that the former slaves were "Neither Slave nor Free."[3]David W. Cohen and Jack P. Greene used this fitting title, Neither Slave nor Free for their insightful book (Baltimore, Johns Hopkins, 1972).

The Alabama constitution of 1819, like that of other Southern states, gave the right to grant manumission by petition to the legislature, and in its first session seventeen slaves were emancipated. Owners were still required to pledge bond as security for that freedman. Emancipation could be obtained by deed (After all this legal action involved the sale or gift of personal property as slaves were considered.); by will; or petition to county courts. Local courts then assumed power over the rights and conduct of all free blacks within its boundaries.

Simultaneously, the General Assembly established a "pass" system, and no slave could legally leave his master's premises without a signed note of permission. Any concerned white could apprehend blacks, enslaved or free, and deliver them to authorities for possible punishment. A patrol law to secure protection against possible slave conspiracies was also enacted.

Among the Acts of Alabama Assembly as early as 1832, patrols were reaffirmed. Each patrol leader was required make a true return on oath to a judge or clerk of his time, his patrol's service, and reimbursement for the patrol's service.[4]Acts of Alabama Assembly, Nov. 1832, 130. (Hereafter cited as Acts.) In effect every white male became a military instrument to enforce white freedom and black slavery.

The duty of the patrol was to visit, particularly at night, all slave quarters and those of freedmen who might be suspected of holding unlawful assemblies. If disorders occurred off the plantation, the master might abandon private discipline and ask the slave patrol or the sheriff to reestablish his rights. As an indication of the seriousness, the militia men were fined ten dollars for failure to serve in their local patrol. In Huntsville's newspapers there were clamors for strengthening the patrol laws because it was commonly known, they claimed, that free Negroes and mulattoes were "more vicious than slaves" and "a source of demoralization." Thus the need for more supervision of possible unruly persons and further emancipations should be halted.[5]Lewy Dorman, The Free Negro in Alabama from 1819 to 1861. Thesis, University of Alabama, 1916, 2; Huntsville Southern Advocate, Oct. 15, Nov. 12, and Nov. 19, 1831.

Patrols generally had the right to invade the homes of blacks, free or enslaved, to search for firearms and administer 20 lashes to any slave found away from home without a pass between sunset and sunrise. Patrols, public punishment and sale of slaves constantly served to remind the free black of his inferior status. This was a painful reminder that most freed people had been slaves at one time.

Freed men and women were considered dangerous examples, and slave owners attempted to limit contact between slaves and free blacks. Thus there were restrictions to the newly-found freedom. Statues and regulations were enacted to prevent loafing and vagrancy among the freed. Children who appeared neglected could be bound out or apprenticed. If the freedman became a public charge, he could be sold into servitude or even permanent slavery.

At the least, these restrictions were to show that newly freed persons would not become a burden on public charity. Also, since free persons of color were considered a disruptive influence, it was thought necessary for government to have firm control over their activities. In most states, because everyone "knew" that Negro gatherings were always "tumultuous and rebellious," the right of free assembly, even in northern states, was often denied.[6]Carter C. Woodson, Free Negro Heads of Families in the United States in 1830, (Washington, DC, Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, Inc., 1925), xxiv As a result, it was against the law for blacks, free or slave, to congregate in groups of more than five or six.

The free black population, which had doubled between 1820-1860,

numbered 260,000 at the beginning of the Civil War.

But how many free persons of color were actually in Alabama, Madison County and Huntsville? In actuality, 99 per cent of the black and mulatto population in Alabama were enslaved. Of the free people of color most, 60%, lived in the five counties of Mobile, Baldwin, Tuscaloosa, Montgomery, and Madison. Most were in urban areas that offered more chances to work for a living and perhaps to blend in, unnoticed.[7]Stewart R. King, ed. Encyclopedia of Free Blacks and People of Color in the Americas. Facts on File, An Infobase Learning Co., nd. 2 Vol., Vol. 1, 19.

One must consider Mobile and its surrounding bay-area differently from the "Anglo American" remainder of the state. Along with its early French settlements, Mobile entered the Union through an 1819 treaty with Spain. Those terms protected the rights of numerous free blacks who already resided there. As a result Mobile became a sanctuary for freed blacks as the state of Alabama began restricting freedmen's rights.[8]James Benson Sellers, Slavery in Alabama. (Tuscaloosa: Univ. of Ala. Press, 1950), 384.

| African American Population of Alabama 1820-1860 | ||

| Year | Free People of Color | % of Total Population |

| 1820 | 569 | 0.40% |

| 1830 | 1572 | 0.50% |

| 1840 | 2039 | 0.30% |

| 1850 | 2265 | 0.30% |

| 1860 | 2098 | 0.20% |

This chart shows the decline in the number of free persons of color within the state of Alabama. Earlier, manumissions had not been uncommon, but more harsh penalties had the desired effect on the population and were reflected by the 1840 census.[9]King, Vol. I, 19.

Restrictions had become increasingly stringent with the passage of time. After January 1, 1833, it was unlawful for free persons of color to immigrate and settle within the state. Free black persons who might move into the state after this date were given 30 days to leave or suffer 39 lashes. If they remained, they could be arrested and sold as slaves for one year. Apparently the laws were not strictly enforced everywhere because free blacks continued to move into Huntsville. (For individual stories and citations, see Appendix III.)

In the years between 1819 and 1829, the Alabama legislators had freed slightly more than 200 blacks. In order to simplify the proceedings, the legislature passed an act delegating to individual county courts the right to emancipate slaves in 1833. Owners were required to publish in a county newspaper for at least 60 days the name and description of each slave to be freed. Those newly freed were to leave the state within 12 months and not return. Failure meant the sheriff could jail the person who could then be sold into slavery. For example, according to his emancipation papers, after the surety bond had been set, Billy Dupree "shall remove out of this State within twelve months." One does not know if Billy really left, but his name does not appear on any records in Madison County after that date. Likewise the papers of Jacob Blake said he "shall remove out of this state….if said negro returns to reside in this State, it shall be the duty of the sheriff…to expose to sale that said negro and the proceeds …be appropriated to county purposes."[10]Acts 1820-1824, Nov. 1823, 78 and 79; approved Dec. 31, 1823. It appears Jacob Blake also moved on.

| Free Negro Population in Madison County, Alabama | |||||

| 1820 | 1830 | 1840 | 1850 | 1860 | |

| Male | 74 | 77 | 105 | ||

| Female | 70 | 87 | 87 | ||

| Total | 46 | 158 | 144 | 164 | 192 |

Unfortunately the Federal censuses of 1820 and 1830 only enumerated the heads of households; spouses and children would not be counted. As a result, families of free blacks were underrepresented in those years' population.

An additional 1822 census showed that Huntsville had just over 1300 inhabitants - 833 whites, 448 slaves, 12 free black males and 13 free black females. At that time slaves made up about 36% of the city population. Free blacks were barely less than 2% of Huntsville's total population and just over 5% of the city's black population.[11]Frances Osborne Robb, "Guide to Information on Blacks in Huntsville, 1805-1820," for Constitution Hall Park, Dr. Frances C. Roberts Collection, Dept. of Archives/Special Collections. M. Louis Salmon Library, University of Alabama in Huntsville, Huntsville, Alabama, Series 4, Subseries D, Box 3, f 9, p 4; General E. C. Betts, Early History of Huntsville, Alabama, 1804-1870. (Huntsville: Minuteman Press, 1998), 56.

It becomes apparent that the number of free persons of color grew within Huntsville. Obviously the free Negro population was not leaving, and emancipations, perhaps of kinship ties, continued even after restrictive laws were enacted. And of course, free parents would want their children to remain with their family if the atmosphere was indulgent about the legal limitations.[12]Dorman, 21. No matter the penalties and restrictions, by 1860 the population of free people in the United States was 260,000 in number.[13]West, Emily. Family or Freedom, People of Color in the Antebellum South. (Lexington: Univ. Press, 2012), 22.

How did these colored men and women obtain freedom within the state and county? Generally masters emancipated those slaves they knew best, not field hands but house servants and those with special skills. It would be too simple to assume that most emancipations came about because of sexual liaisons between white masters and female slaves and any resulting children. Certainly this would appear to play a role, and the number of mulattoes had increased. According to one study, approximately 78 percent of Alabama free Negroes were mulatto (or of mixed racial heritage).[14]Gary B. Mills, "Miscegenation of Southern Race Relations" in Journal of American History,'' #68 (June 1981), 19. A recent work by Bernie D. Jones, ''Fathers of Conscience (Athens: Univ. of Georgia Press, 2009) examines in great detail Southern high-court decisions involving wills of white male planters who made bequests to women of color and their mixed-race children. Most important to the children of free mothers, they had the status of their mother - that of freedom.

Nevertheless, slave owners did not free all mulatto children. These light-skinned children might receive special training or privileged places within the household. In a time when "The Negro's color served as a badge to remind the public of his ignoble position…." the lighter skin tone of the mulatto allowed a social standing above the black slave and often above the free black population.[15]Woodson, xvi.

The unwritten double standard of white society at the time closed an eye to the white male exploitation of Negro women, but tolerated few sexual relations that hinted of racial equality, such as white female relations with Negro males. Worse still, this same ruling social order was appalled at the possibly of interracial marriages.

One writer who conducted extensive research in Alabama concluded that the assumption of the free Negro class owed its origins to white planters' manumission of slave offspring. This is unsupported. The number of mulatto children manumitted by white fathers constituted only a small percentage of the total mulatto population within the state. That certainly appears to be the case within Madison County records.[16]Mills, "Miscegenation," 19.

Exceptions might be found. In 1824 Madison County Sheriff William McBroom, set free his slave, Gamaliel, as Peter Fagan, father of the boy, entered into a one thousand dollar bond. Later the wealthy Townsend brothers, Edmund and Samuel, attempted to emancipate their acknowledged children by will.

Emancipation by public action' might come as a reward for '''meritorious public service. Pierre Chastang of Mobile was bought and freed by popular subscription in recognition for his service carrying supplies to General Jackson in the war of 1812. During the yellow fever epidemic, which many fled in 1819, Chastang remained to tend to the sick and bury the dead. At his death, the ''Alabama Planter'' wrote that he was a "highly esteemed and respected" member of the community.[17]Edward Franklin Frazier, ''Free Negro Family'' (Nashville: Fisk Univ. Press, 1932), 3; William Warren Rogers, Robert David Ward, Leah Rawls Atkins, Wayne Flynt, ''Alabama the History of a Deep South State (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994), 108-111.

The slave who saved the Georgia capitol building from burning in 1834 was set free. Courageous acts might be rewarded with freedom, but this was not always the case. One slave who acted heroically to extinguish a fire in the Sumter District of South Carolina was rewarded by the Legislature with $100, but not emancipation.[18]John Hope Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom,'' (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994), 149; Maria Wikramanayake, ''A World in Shadow. (Columbia, University South Carolina Press, 1973), 38-39.

Sally Phagan in 1829 was purchased and freed by contributions of "sundry citizens" of Madison County. Apparently not considered a risk to flee or do harm, the surety bond was set at only $100. Here also Catherine Butcher emancipated her man slave, Tom Walker, for "long faithful and meritorious services."[19]Acts, 1829, 36-38, Nov. 1829, approved Jan. 20, 1830; Madison County Orphans Court Minutes, 1840-1842, 480. (Hereafter cited as Orphans.)

Manumission through an owner's will was legal if a means of support and preparation for free status was provided in the document. A trustee would be appointed to see to this, and some slaves received their freedom at the death of their master. (Even so, Alabama law prohibited widows from freeing other slaves at the time of their husband's deaths.[20]John F. Baker, Jr. Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation, (New York: Atria Press, 2009), 76.)

Daniel Brewton manumitted his Negro slave Davie by his will in 1829. According to his wishes, Brewton's will also bequeathed to his wife the slave woman Fanny until either Mrs. Brewton moved away or died. Then Fanny would become free. And at Mr. Brewton's death, the Negro man Sam was bequeath to his son, Samuel Brewton with the understanding that the slave would also be free at the son's death.[21]Will Book I, 219; Deed Book B, 58; Gary B. Mills, "Free Africans in Pre-Civil War 'Anglo' Alabama: Slave Manumissions Gleamed from County Court Records" in National Genealogical Society Quarterly, Vol. 83, #1 (March. 1995), 208; Deed Book O, 25; Acts 1829, 1836-38, approved Jan. 20, 1830; Deed Book U, 317; Deed Book O, 150; Deed Book P, 134.

In many cases, the wishes of the dearly departed were confounded by others. The slaves Winney, 60, "a very old woman;" her son Lige, age 40, and a second son Jo, 32, who was an "idiot" were all to be freed according to the will of one Henry Townsend. Townsend also stipulated that Winney would have a four-year-old mare, one cow and calf, six geese, one flax wheale, one cotton wheale and cards, the bed and furniture and earthen ware that belongs to her house." Sadly, Winney and her family never benefited from these bequests; the will was declared null and void by the Alabama Supreme Court in 1838.[22]Henry Townsend. Madison County, Alabama Probate #526. (Hereafter cited as Probate.)

Certainly the largest and most complicated cases of manumission by will in Madison County would take years to resolve. Edmund Townsend, and his younger brother, Samuel, left Lunenburg County, Virginia in the 1820s and were counted as among the privileged of Madison County planters. Neither brother married. They settled near Hazel Green and began buying land from nearby small farmers. Edmund's estate at his death in 1853 was valued at $500,000. His will was very clearly written, and he intended his entire estate to go to his two mulatto daughters, Elizabeth and Virginia. The courts, nonetheless, declared his will void. It was illegal for a testator to convey property to slaves. The women were slaves and as a result they "could not hold property, acquire title by descent, gift, purchase or finding."[23]Sellers, 230. The Alabama Supreme Court had earlier ruled that a person could not any longer emancipate his slaves by his will; they were still slaves - personal property - and thus were unable to own property on their own.

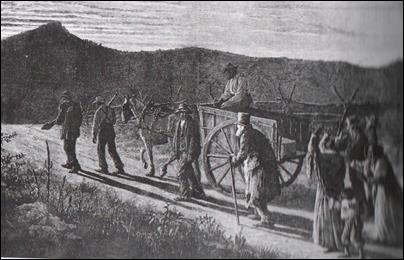

Samuel Townsend paid closer attention to the wording of this 1854 will than this brother Edmund had. Samuel was a wealthy man; his estate had grown from 43 slaves in 1840 to 86 slaves and $25000.00 in real estate in 1850 to a total of 8 plantations (covering about 7,560 acres) and 190 slaves at the time of his death in 1856. His slaves were first to be removed to Ohio and then emancipated there. He provided a trust fund from the sale of his estate for them for this purpose. Included in this group to be removed were nine mulatto slaves who were Samuel's children, Elvira his housekeeper and Elizabeth and Virginia the children of his brother Edmund. A second group of 28 slaves were to follow the first group to Ohio. Although the will was contested for two years, Rev. W. D. Chadick travelled to Ohio and made all the preparations for their emancipation, housing, and maintenance. He then accompanied the slaves to Ohio to help them become established.[24]Frances C. Roberts, Thesis, "An Experiment in Emancipation of Slaves by an Alabama Planter," University Alabama, 1940. Passim.

Although the crippled and elderly, who were deemed "past labor," might be discarded by uncaring owners, there were emancipation examples of rewarding faithful service of a long-time slave. However one writer, accounting for the number of former slaves in Southern and Northern cities, suggested, "the unpleasant and oppressive fact that the aged and infirm and worn-out Negroes" are many and they migrate to the city.[25]Richard C. Wade. Slavery in the Cities (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1964), 141.

The wording in the following case, however, suggested a kind relationship and perhaps a bond of affection and appreciation. In Madison County, Tom Walker was emancipated by Catherine Butcher in July 1842 for "long faithful and meritorious services." Likewise the will of Gallanius Winn, who died in 1839, freed, "For the kind attendance of my old Negro Hanna, her freedom."[26]Orphans 1840-42, 480; Probate #A, 30; Mills, "Slave Manumissions," Sep. 213; Probate, #194.

In Madison County the most common emancipation examples appear to be slaves who were able to purchase their own freedom or that of family members. A slave who was allowed to hire out his own time might be able to save enough money to bargain with his master for self-purchase. For instance the Townsend brothers allowed their slaves to grow small patches of cotton and sell it to their masters. In 1860 thirteen slaves sold the cotton they had raised themselves for a profit of almost $1000.[27]Roberts, 8; Cited in Sellers, 74. Many men had learned skills on the plantation, such as farming, shoe-making, blacksmithing, barbering, that would be useful almost anywhere.

Women might accumulate butter and egg money, and they, too knew the value of a garden, particularly in an urban setting. They could hire themselves out for domestic positions such as housekeepers, maids, cooks and laundresses. Among these women, there might be a traditional healer who understood the uses of medicinal herbs and assisted with birthing. One may easily surmise that a midwife with a good reputation for care and results might be called to attend white women as well as black, slave or free. This woman would likely know of available wet nurses, as well.

Although the amount of money was not recorded, in 1838 Dr. Alexander Erskine, in a strong testimony, acknowledged the self-purchase and free pass for his "boy" Alfred, age 39, who, by his own industry and savings, earned his freedom. The free pass included Alfred's description to prevent him from being arrested as a runaway when he went to any free state, as required by law. In January 1824 Mary Ann Grason [Grayson] bound her Negro, James Poston, for the sum of $1800. She sold to James his own time for life for $900 current money or bank notes in three installments.[28]Deed Book Q, 617; Mills, "Free African Americans," June, 137; Deed Book M, 84; Acts, 1820-24, 124, Nov. 1824, approved Dec. 4, 1824.

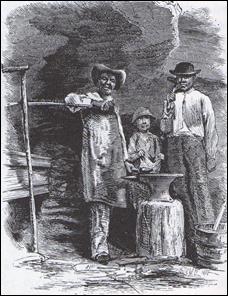

During these years it was not uncommon for free persons of color to own slaves themselves. The 1830 Federal Census noted ten different free black persons in Madison County owning 15 slaves, Betsey Davis and Jacob Broyles each owned one slave for instance. By 1840 three owners had eight slaves between them, and among them two women, Nancy Jones and Elizabeth Barker, owned one slave each. In 1850 three owners had eight slaves that included Henry Walker, a blacksmith who owned four slaves and Charles and William Sampson, also blacksmiths, who owned two slaves each. Most often these slaves appeared to be spouses or children of the freedman. The 1860 census offered a separate Slave Schedule and none of those previously listed as slave owners were listed still as owners. One hopes these people were able to purchase those slaves who might be family members.

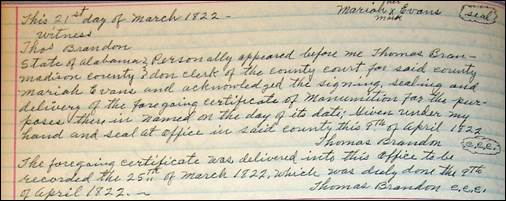

A number of slaves became free by running away from their masters. Local newspapers were full of advertisements for the capture of runaway slaves. Many migrated into the towns where they could be less obvious and were able to find work. Some remained in hiding until they could decide what to do next. Daniel camped out near Capshaw's Mountain and Peague's Mountain near Price's Big Spring and his owner, John Lucas, in 1829 acknowledged Daniel to be "smart, sensible and cunning." However Samuel Cruse's slave Norvall ran away most likely to join his wife and child left behind in Virginia.[29]Daniel S. Dupree. Transformation of the Cotton Frontier. (Baton Rouge, Louis. State Univ., 1997), 204-237. This book offers meticulous research and solid understanding of the condition of blacks in Madison County - in bondage and free.

Not surprisingly, few women chose to flee who might be encumbered by their own children and elderly family members during their escape. Of course, if the runaway was able to get far enough and was captured, he or she might claim already to be free, and no one would know the difference. For mulattos, the whiter their appearance, the better was their chance to be believed. Papers could always be forged, perhaps by a literate freeman or a sympathetic white man.

Not unusual for the times, the very poorest families could send a child to be Bound Out, or apprenticed, to someone who appeared to offer a chance for the future but more likely just for daily food and clothing. For instance Daniel Patterson, a boy of color, eight years and orphaned, was bound out to Albert Russel to be taught and instructed as an apprentice in the arts and mysteries of the farming business. Five of the children of Keziah Clifton, a free woman of color were bound out.[30]Probate 9, 121, 384-5; Probate Case #2458 - A, B, C; 1865 Freedmen Census of Huntsville. (Hereafter cited as 1865 Census.)

For any of several reasons reasons, a free person of might ask for Voluntary re-enslavement. As restrictions increased within the bureaucratic system, Alabama allowed, by law, "free negroes to select masters and become slaves." Of course the free person of color should apply to some white person of good moral character for this "guardianship." The process was to be free from undue influence and these new slaves "shall not be sold under any legal process for the debts or liabilities of the master or mistress they have selected, or their heirs or distributes." No ruling was enacted to keep the new owner from selling his recently acquired slave.[31]Cited in West, 35, 36.

Consequently, by law, any free Negro might select a master and take the status of a slave again. As tensions in the South increased, some free people of color chose to be re-enslaved. Forced migration had become a condition of freedom within most states, but the neighboring state often did not allow immigration into their boundaries. Although these new laws of expulsion were not always implemented, fear was a constant reminder. If there was any doubt of the white man's intentions, Virginia's George Fitzhugh wrote in 1851, "Humanity, self interest [and] consistency all require that we should enslave the free Negro." Dr. Samuel Cartwright, who began his medical career in Huntsville, popularized the idea of lifelong bondage as a natural solution: "There would be no free blacks to aid runaways, and as a bonus, the labor supply would be enlarged to the extent of selling new slaves to the poor whites."[32]Ibid, 24.

Those asking to be re-enslaved were most often mothers with children to support and little income. And a husband whose spouse was still enslaved with their children would have to choose his own personal freedom against being with his family. As anxieties increased near the start of the Civil War, George Washington Davis petitioned to be re-enslaved by Thomas Studdard. Perhaps his wife or children were on the Studdard plantation and he wanted to join them, or Davis may have felt as though he needed protection in uncertain times. John Williams also petitioned according to the records in 1860 to become a "slave for life" feeling that being free was "mostly theoretical" and he was "wedded to the South" with his master, Thomas Douglass. Surely, someone enhanced the words for this noble petition by a black man who by definition could not read or write.[33]Probate, 1860-1862, 109-110; Probate, #2442.

Living as Free became an alternative for masters unable to afford the taxes and bond involved in emancipation for their slaves. This freedom "by courtesy" was illegal but not uncommon. Masters might simply allow their slave to go free without any legal certification of their status. In this case a slave would perhaps have a pass or letter to protect him from authorities. However, under the law they were still property of a master.[34]King, Vol. II, 448. This arrangement could serve as a reward for good service and as an incentive for other slaves to work harder.

A slave "living as free" might try, when the agricultural workload was low, try to pursue another trade, or even open a small business. While women might "live as free", they also lived under the restrictions that any children they gave birth to were still the property of their owner.

Yet, this almost-free-but-not-free condition left the master responsible for the actions of a man or woman still his slave. If the slave, "living as free" was caught stealing or harming someone's property, the master was required to make restitution. Ever watchful legislators in Arkansas enacted fines of $500 after March 1843, on anyone who did "employ, harbor, or conceal any Negro or mulatto "acting as a free person."[35]West, 27.

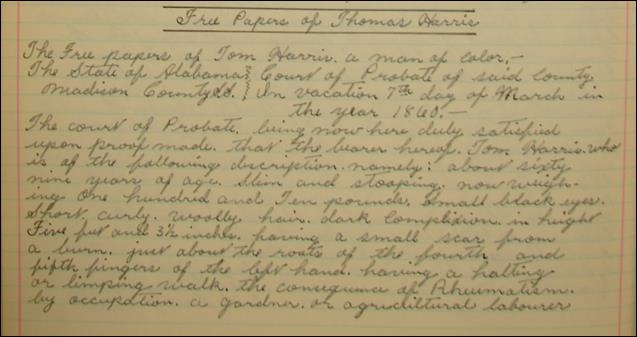

The complexity of legal emancipation was lengthy and expensive, beginning with action by the state assembly or local court. After petition, deliberation, and approval the next step involved the local county court with even more paper work. Fees had to be paid to the clerk for filing papers and making copies. For instance, in 1843 the Madison County Clerk charged 18 3/4 cents to file papers and certificates; copying costs were 25 cents. Witnesses could ask for remuneration for their time and travel, and lawyers' fees always had to be paid. The legal formalities of freedom, once completed, sometimes took four to five years. Molly Lee complained that the action to legally free her husband Taylor Ragland for some inexplicable reason was delayed. His papers had not arrived and yet his time to leave the state would soon expire. Freemen and women were required to carry their papers, which included their written description, at all times. Southern law assumed all blacks to be slaves, and thus any and all blacks might be arrested, jailed, advertised, and, if unclaimed, sold. The need for legal papers, at whatever the cost, was essential.

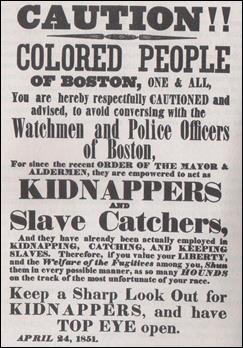

Once at liberty, perhaps the greatest fear for a newly freed person of color was the possibility of being stolen and re-enslaved. Kidnapping in some states had become so blatant that the crime became a capital offense. For instance, in Delaware the punishment for kidnapping a black person was 39 lashes and both ears nailed to the pillory for an hour and then cut off.[36]Berlin, 99.

The theft of black men and women was a constant threat. In 1829, Charles T. Collins was hanged for stealing Negroes in Huntsville; Allen Cotton stole Charlate and Olen in 1837 and was sentenced to be hanged. In 1834, Welcome Hawkins was sentenced to death for stealing a slave; David Clark was convicted in 1841 of Negro stealing and was hanged.[37]Madison County Circuit Court Minutes, Sept. 10, 1820. In 1823, Daniel Rogers and John Merriman were indicted by the Madison County grand jury for "feloniously stealing and carrying away" a free Negro man. One does not know the punishment for Rogers and Merriman, but in North Carolina, the penalty for capturing a free Negro and selling him out of state was death - without benefit of clergy.[38]Dupree, 151; John Hope Franklin. Free Negro in North Carolina, 1790-1860. (Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1943), 56; Madison County Circuit Court, Nov. 6, 1823, 53. (Hereafter - Circuit)

On a more grand scale, one local case of theft of slaves involved a law suit for payment of debts of over $15,000 that had begun in Virginia. Egbert Harris, in Huntsville by 1820, "ran Negroes off to Tennessee and sold them." As insignificant as that might seem, he actually stole, by means of "fraud and collusion," 52 slaves. Obviously deeply in debt, that same year he owed Willis Pope $31,000. (His move to become an overseer for one of General Jackson's plantation was timely, but a few months later, apparently there was a discrepancy in his account books. Even the General had been deceived.) Egbert Harris was seen no more hereabouts. Circuit, #4966; Nancy M. Rohr, "The News from Huntsville: in Huntsville Historical Review, Vol. 26, #1 (Winter-Spring 1999), 3-23.

Little matter these various methods of emancipation - by will, by law, by self-purchase, or reward for faith service or meritorious deeds, "The ex-slave was not a free man; he was only a free Negro."[39]George Washington Cable. The Negro Question. Cited in Berlin, 381.

Although black and white people often lived side by side, the separation was unyielding. "We reside among you and yet are strangers; natives, and yet not citizens; surrounded by the freest people and most republican institutions in the world, and yet enjoying none of the immunities of freedom ... Though we are not slaves, we are not free."[40]"Memorial of the Free People of Colour of Baltimore," African Repository, Dec. 1826, cited in Berlin 133

Most free people of color lived in town clustered around other modest black and white, poor and working-class people but still convenient to upper-class households who needed their services. Housing probably was not good for any of these families and restricted to small areas in back alleys, above stores, dank cellars or unoccupied sheds and lean-tos.

Some few Madison County free blacks lived outside the one square mile of Huntsville town limits. The Sikes (Sykes) family was at the Hayes Store District at the village of Deposit in the northeast part of the county. Caleb Tyler lived independently in Madison Station as did Frances Marshall and Moses Ward, a shoemaker. Charles Sampson the blacksmith also was listed at Madison Station. To the south the Jacobs families lived near Triana and owned property there. At New Hope, D. W. Brewer was a shoemaker and Dennis Jackson a laborer.

One must also consider that it was not unusual for the spouse and children of a free person to remain enslaved, and making the trip to the plantation to visit sometimes became a problem, and even a danger. Throughout the county, the free person technically had liberty of movement, but they were aware at all times that any white person could seize them and demand to see their papers.

Like most of their white neighbors, the lives of free blacks centered on work, family and church. Putting food on the table and clothing on their backs required most of their time and energy. Additionally, they also might fish at nearby Pinhook Creek or hunt with traps in the woods at the edge of town. (It was against the law for blacks to have weapons.) Free people of color would never expect to sit with whites at a public gathering and much less enter the Opera House, the local epitome of white culture. If the law was strictly adhered to, taverns, restaurants, and hotels were also off limits.

While free blacks had little time for entertainment, they might occasionally gather at a horse race or cock fight. Political figures of the day held frequent barbeques, and black people were almost certainly involved. At the very least, they cooked, served, and cleaned.

Enthusiasm among the freemen sometimes got out of control when the work was done. Local citizens complained about Saturday night merrymaking and misbehavior the next day at the Sunday market. The Democrat complained that the blacks apparently had more "fashionable" parties than their white neighbors and certainly were more raucous. The patrol apparently was not doing its job and should be more attentive to their duty. As a result, black activities became more curtailed in town. With the feared threat of rebellion in the fall of 1835, slaveholders were not to allow neighborhood gatherings for shucking corn, sewing quilts, night prayer meetings, or any other occasions where slaves and freemen might traditionally gather together.[41]Huntsville Democrat, Sep. 9, 1835; Dupree 229-30.

Restricted from taverns and billiard halls (where alcohol was sold), free blacks socialized in black-owned "cookshops" and grocery shops where sometimes they could buy a drink of liquor, even if it were homemade. Gaming, and side bets on the players, was unlawful for whites as well as blacks in Huntsville. There would be no legal cards, dice, Faro, gaming tables, lotteries, thimbles or Rowley-Powley.[42]Huntsville City Aldermen Minutes, May 13, 1833, #59, 238. (Hereafter cited as City Minutes.) However the laws did not stop white men from such activities, nor, most likely any blacks who were so inclined - free or enslaved. Town slaves and freeman would know where to look for such action as did those few whites not welcome at their own taverns any longer. Groggeries usually did good business and partakers would spread the word when patrols were about.

Unlike the slave, a free person of color was his own master, possessing the right to his own labor, his own occupation, and hours. In Alabama he had the right of marriage without asking permission unless the intended spouse was still a slave; the master then had to agree. Many Negroes were accustomed to "jumping backwards over the broom" as part of the ceremony to see which one of the couple would be the boss. But the words of the ceremony often mentioned the couple would be married "as long as distance did not separate us", for instance, if the slave owner moved away. The respect for the sanctity and legality of marriage led freedman Charles Sampson, in 1822, to make the trip into town from Madison Station for a marriage license for himself and Irerer Smith. Their daughter, Matilda, also had a license for her marriage to Nelson Earls in 1855.

The 1805 and 1833 marriage codes allowed officials to "solemnize the rites of matrimony between any free persons" who presented a license. By 1852 the Code of Alabama contained a significant change. Article #1946 noted that "marriage may be solemnized between free white persons, or between free persons of color, by any licensed minister" while #1956 added, "Any person solemnizing the rites of matrimony, with the knowledge that … one of the parties is a Negro [slave or free] and the other a white person is guilty of a misdemeanor."[43]Mills, "Miscegenation," 18.

A mother could now enjoy the freedom to name her baby to her liking. There was a surname, often hers, and the choice of a first name unlike those meaningless classical names Brutus, Cicero or Hannibal often chosen by masters. Now one could chose a name because they liked the sound or for a favorite person. Each of the adult children of John Robinson, who had children, named a boy for their father, John.

Responsibility for medical care was an additional hardship that accompanied freedom. As the slave owner had provided food, clothing, and protection for his slaves, he also had taken care of their health. Previously, a slave owner might request and pay for the doctor or midwife's attention to their household. For instance the cost to slave owner Dr. David Moore in 1845 for the services of Mrs. Keys, the midwife was $4.00 per visit and, for the doctor, $2.50 per visit.[44]Probate #1204, Dr. David Moore, 1845 Now, because of less experience and little money, free people of color were less likely to ask for medical help. As a result, free blacks had a high mortality rate. This appeared to enforce and validate the claims of many Southern whites that blacks were better off being enslaved and cared for.[45]Wade, 141.

Free blacks appear to have served as a buffer between white and slave populations, but theirs offered no real status in society except within the small group of others like themselves. All social life was simultaneously tempered by facing expectations and restrictions of white citizens of the community, who were ever watchful. Seldom would a free person of color try to attract attention. None the less, generally acceptable for gatherings, certainly from the white man's perspective, every community most likely had a black church or two.

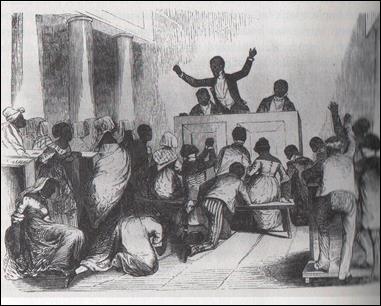

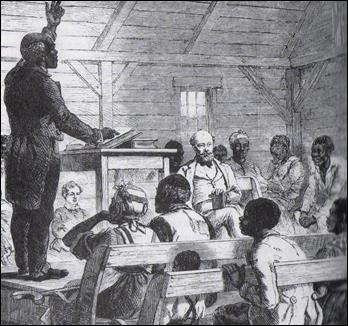

Southerners were proud to note they encouraged blacks to attend church. Religious instruction by slave owners served to teach slaves the white views of morality and obedience. Some allowed slaves to attend their master's church, sitting in the back pews or the balcony. The message often came from Ephesians 6:5, "Servants be obedient to them that are your masters." Perhaps less seldom heard was Colossians 4:1, "Masters, be just and fair to your slaves. Remember that you also have a Master in heaven."

The restrictions placed on their church services, one observer, Presbyterian minister Charles Colcock Jones in 1832 noted, as the results of "religious persecution, secrecy and nocturnal meetings" led to more secrecy in old fields and plantations."[46]Rev. Charles Colcock Jones. "Religious Instruction of the Negroes, A Sermon." Rpt. Bedford, Mass.: Applewood Books, n.d.), 32. This attitude provided further validation for those who argued that religious instruction and behavior of blacks be constantly supervised. Observation by white men must, by law, accompany any religious service with more than five or six members.

Even in these circumstances, almost everyone felt strong ties to their religious beliefs. "As among our people generally, the Church is the Alpha and Omega of all things."[47]Martin Delany to Frederick Douglass, Feb. 16, 1849. Religion became the hub of many blacks' social life, even as they were aware that, by law, a white person would be present at the majority of gatherings.

Visiting Huntsville in 1822, Anne Royall wrote that there were at least two black churches and a prayer meeting every night. One, the African Cottonport Church just south of Mooresville on the Tennessee River, was led by a slave named Lewis and had a membership roster of 130 people in 1840.[48]Sellers, 300; Stephen R. Robinson, "Rethinking Black Urban Politics in the 1882: The Case of William Gaston in Post-Reconstruction Alabama," in Alabama Review Vol. 66, #1 (Jan. 2013), 5.

The highly respected free colored Huntsville minister William Harris, founded, organized and was the original pastor in 1820 of the First African Church, later known as St. Bartley's African Baptist Church. This group entered into the Flint River Primitive Baptist Association in 1821 with 76 members (a number which probably included town slaves, as well as free black men and women.) William Harris served as the first elder there and Bartley Harris, his grandson, was the second of this association.[49]Berlin, 284; Anne Newport Royall, Letters from Alabama, 1827-1822, ed. Lucille Griffith (Univ. Ala., Univ. of Ala. Press, 1969), 248; "History of St. Bartley Church" from The Order of Service, Aug. 26, 1962.

Burial services, likely at Old Georgia Cemetery on the southern edge of town, might provide an occasion without the required white supervision of black events. Funerals, like church services, could be enthusiastic, emotional, and prolonged, with eulogies, testimonials and singing. Naturally, family, friends and neighbors lingered together after the services. White citizens, in such a small community, might have chosen not to supervise these activities in the strictest manner required by law.

He was an honest upright man in all his dealings."

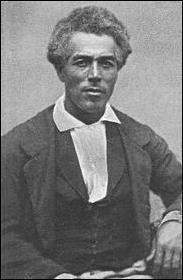

Few had such a favorable obituary in a white newspaper as that of Lafayette Robinson.[50]Huntsville Advocate, Feb. 6, 1878. A small number of other Alabama freemen became quite successful by any standards. Horace King, a slave owner himself, designed some of the finer details of the Alabama state capitol building and was an extraordinary accomplished builder of bridges in Alabama. He later served in the Alabama House of Representatives. Solomon Perteet, a planter and merchant in Tuscaloosa, was successful enough in his business ventures to lend money to white men. John H. Rapier, a freed slave, became a barber in Florence, Lauderdale County and accumulated $47,500 worth of property. His son James T. Rapier, educated in Canada and Scotland, served as one of Alabama's three black congressmen during Reconstruction. James operated a newspaper and remained a powerful politician in Alabama.[51]King, Vol. I, 20.

The four free black families in Madison County that left the most information about their lives and dealings appeared to have skills that were necessary for success. Undoubtedly, they were careful to be straightforward in their dealings with the white community, always cautious not to cross the fine line regarding their position.

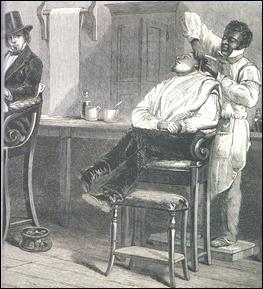

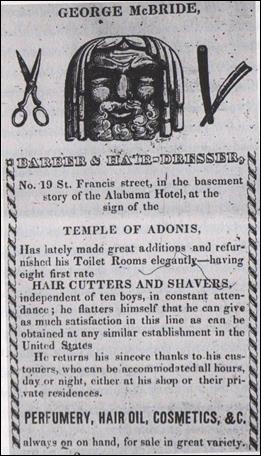

For the Terrell families, the barber shops and bath house required a fastidiousness that few other blacks might be able to bring about. Smartness of the shop, their apparel and their own cleanliness was very important to their clientele. Many customers were accustomed to valet service at home. The barbers offered amenities unavailable to many, and it was a mark of distinction that one's personal grooming would be attended to by others.

The livery stable owned by the John Robinson family was significant in Huntsville. Not all local men could afford the upkeep and space necessary for a horse of their own in town. Anyone arriving by stagecoach or by train who needed transportation would likely stop there, particularly since it appears to have been the major livery establishment. Men of the South were particularly proud of their horses, and Robinson must have had discriminating judgment. This was hard work that few whites were eager to perform for others - dirty, smelly on the coldest or the hottest days.

In the rural setting of the county, the blacksmith offered specialized services for their nearby communities. The work was hard and required strength and patience to forge utensils, horseshoes and make repairs to tools. Everyone needed metal work done, but few had the necessary ability or equipment. Coal or charcoal, often as much as two bushels a day, had to be supplied constantly. A blacksmith's day began before dawn to pump the bellows to heat the forge effectively and to shape the metal on the anvil. Why take the trek into town, when the Sampsons, father and son, were available at Madison Station?

Near Triana, then a thriving port village on the Tennessee River, several families of related Jacobs had arrived from South Carolina perhaps as early as the 1820s. Many of their neighbors were kinfolk and the ties were close. Burwell Jacobs was able to farm successfully enough to be able to purchase more land as did other relatives. Most members of this extended family were buried, in now unidentified cemeteries on their own property now located on Redstone Arsenal land.

At the work places on the farm, at the barber shop, livery stable, and the blacksmith shop there would be conversations among the white customers or the neighbors. Seldom encouraged to join in, the free blacks often became good listeners. As a result these free black businessmen could be well informed about the events, the people, local politics and elections, trials at the court house, and who might be in jail that week or going to jail next week.

The standards of white men who entered the business establishment of a free black person, tended to expect a proper demeanor - humbleness. Therefore, at least in public, high standards were set for himself and the conduct of his family and slaves. In town and country in their dealings with whites, politeness was the rule - employees and slaves were constantly ready to accept that every customer was always right.

Some freemen who had acquired wealth saw themselves proudly enjoying a few status symbols of the whites, even if they were careful not to flaunt it. One wonders if Richmond Terrell wore his fine gold watch or if the Robinson men, John and Lafayette, displayed their gold watches outside the privacy of their homes. The upper class of free Negro society was very limited to those who were also outwardly successful. These few families remained close-knit and married within their limited group.

Although blacks, free or enslaved, were not legally taught to read and write, some must have learned, at least, to read stories and verses from the Bible. Men and women in business had to be able to keep basic accounts. Business men John Robinson and London Urquhart purchased land in Huntsville as did Susannah Young and Molly Lee, all free people of color. But if there was a doubt, after 1832 any free person of color who might attempt to teach a black person, slave or free, to read and write could be fined no less than $250 or more than $500. Any free person caught forging a pass for a slave would receive 39 lashes and be forced to leave the state with 30 days.[52]Acts 1832, 16-17. All free blacks signed any legal papers at the court house with an X - as did most of their white neighbors. (One must also consider it would not do for a black person to appear to write his signature easily or to read, considering it was against the law.)

Unfortunately the struggle of the free blacks to support themselves and their families was often in direct competition with other groups of the available workforce - slave labor, slaves hired or owned by the local township, and the lower-level white workers. Most whites considered working alongside blacks - slave or free - to be demeaning.

Yet, "The free negro performs many menial offices to which the white man of the South is adverse. They are hackmen, draymen, our messengers, and barbers; always ready to do many necessary services; if they are driven from the Southern States who will supply their place."[53]Nashville Republican Banner, Jan. 15, 1860, cited in Berlin, 217.

The livelihoods of free persons were most likely learned at jobs while they were enslaved. Among some, Willie Shavers and John Franklin were farmers, Moses Ward was a shoemaker, James McClung was a plasterer, John Petus a bricklayer; Tom Harris and Shadric Horton were gardeners, Sam Martin was a laborer, as was Mary Walton (Mary was independent enough to be counted as a separate household with her two children.); Martha Martin was at the boarding house as a cook, and, Lewis Harris a drayman.

"Jacob, shall remove out of this State to reside within the same at no time, thereafter. … if said negro returns to reside in this State, it shall be the duty of the sheriff of any county to which he may so return, to expose to sale the said negro."[54]Acts, 1820-1824, approved Dec. 31, 1823.

The General Assembly of Alabama passed several acts, beginning in 1822, to oversee the activities of free Negroes. Except for Mobile and Baldwin counties, free Negroes were prohibited from keeping taverns or selling spirituous liquors of any kind. The first offense was a fine of ten dollars and twenty-five lashes for a second offense.[55]Dorman, 3. Generally tax assessments of freedmen were larger, their fines heavier, and physical punishment more violent. In all Southern counties, ordinances typically inflicted lashes on a slave offender rather than fines for violations.

In the Deep South whippings were meant to humiliate one's manhood or, at the very least, their standing in society. The Southern gentleman's code of honor by use of the cane or horsewhip to attack inferiors or punish slaves announced that "they" were never honorable enough to challenge to a duel. Public chastisement was well-grounded in the legal system of the day, and lashes were the ultimate symbol of white authority. "No man should use a cowhide on a white man. It is a cutting insult never forgiven by the cowhided party because a white man's nature revolts at such degrading punishment."[56]Louisville Daily Courier,'' May 3, 1855 and Richmond ''Enquirer, Aug. 5, 1858 cited in Berlin, 334. This proved, once again, that freedom did not alter the black man's status.

Consequently, whites faced fines as punishments but free people of color, man or woman, and slaves (who generally didn't have money anyway) were lashed on the bare back, for which the constable was paid one dollar for each whipping. Free pass papers and notices of runaways in the newspaper attest to the violence of punishments with descriptions of noticeable scars and disfigurations.

These free people of color were never citizens by any means and were continually punished further by the legal systems to which they contributed. For instance, newly arrived free blacks were required to report to the mayor and pay a five dollar tax just for coming into Huntsville.

The Poll tax included in the earliest records of the Assessment of Taxes on Personal Property (1856) for Madison County show additional charges. This assessment taxed white males between the ages of 21-45 at $1 a person. (Southern ladies, of course, did not pay a poll tax.) However, free females of color between the ages of 21 and 45 were assessed $1. Free males of color between the ages of 21 and 50 paid $2. For instance prominent citizen John Withers Clay paid his assessed $1 and none for his wife. At Whitesburg free colored Denis Jackson paid $2 and Martha Jones paid $1.[57]1857 Assessment of Taxes on Personal Property for Madison County, Alabama.

The Assessment of Taxes on Real Estate was the only institution in Madison County which did not appear to penalize blacks for their free status. For instance, Burwell Jacobs in Triana owned 170 acres and another 40 acres valued at $140 and $.05 respectively. He was taxed 80¢ and 1¢ similar to the rate of his white neighbors. In Huntsville among the few black land owners were William Terrell (one lot valued at $600, taxed $1.20), John Robinson (one lot $1,000 taxed $2), and Mourning Vining (one lot, $400 taxed 80¢).[58]1857 Assessment of Taxes on Real Estate, Madison County, Alabama.

By the 1820s, nonresident free blacks who remained more than 20 days were subject to arrest and long term indenture. Those found "in idleness and dissipation, or having no regular or honest employment" were typically arrested and bound out. Free children of impoverished free black women were sent to the poorhouse to be bound out as farm laborers and thus not an expense on the county. For instance the overseer of the poor in the county was asked to examine the infant children of Belzy [Betsy?] Davis, a free woman of color. If the overseer felt there was a need, her children would be taken to the poor house and later bound out. The children were removed from her care.[59]Wilma A. Dunaway. Slavery in the American Mountain South. (New York: Cambridge Press, 2003), 53; Orphans 1810-1819, 96.

According to the 1860 Federal Census, Mat Kenney, supervisor of the Poor House was responsible for the inmates - four souls noted as being idiots, one listed as insane, and six paupers. None were listed as being black or mulatto; if they had been, they most likely would already have been bound out for labor.

"Living above a loaded mine, in which the Negro slaves were the powder, the abolitionists the sparks, and the free Negroes the fuse."[60]U. B. Phillips. "Racial Problems, Adjustments and Disturbances" in South and the Building of the Nation, IV, 236 quoted in Sellers, 361.

Generally, white southerners made no distinction between slaves and non- slave blacks. Everyone of African descent represented a potential insurrectionist. As early as 1785 North Carolina ordered all urban free Negroes to register with the town commissioners and to wear a shoulder patch inscribed with the word "FREE."[61]Berlin, 93. All the better to watch them and their activities!

The successful 1791 revolution in Haiti to eliminate slavery in the French colony of St. Dominique was fair warning as refugees, black, white, and mulatto, fled to port cities of the United States, including Mobile.

The laws of southern states had become more restrictive as fears of uprisings grew. In 1822 Mississippi owners could be fined ten dollars, for permitting free blacks or slaves they did not own on their plantation for more than four hours without a pass. Free blacks were "registered and numbered in a book that identified them by agent, name, sex, color and stature as free, mulatto and any visible distinguishing marks and how they had obtained their freedom." If free blacks returned to Mississippi after emancipation, they could be arrested by the sheriff and punished with up to 39 lashes and required to leave within 29 days. Those who failed to leave would be sold as slaves. These laws were quickly enacted in Virginia, Maryland, Kentucky, and even Delaware.[62]West, 30, 31; Frazier, 4. Soon all Deep South states enacted restrictive legislations and there seemed to be enormous justification of their fears.

The revolt in Charleston, South Carolina by a free black man, Denmark Vesey, resulted from a lifetime of rebelliousness and at least four years of intensive planning. It was said of Vesey, "Even whilst walking through the streets … if his companion bowed to a white person he would rebuke him and observe that all men were born equal …" He and his co-conspirators, both free and enslaved, planned an uprising on Bastille Day, July 14, 1822. Word leaked out and the plot's leaders were arrested and tried. In the fear and hysteria 131 blacks were charged with conspiracy, 67 convicted and 35, including Vesey, were hanged.[63]An Official Report of the Trials of Sundry Negroes Charged with an Attempt to Raise An Insurrection in the State of South Carolina, 1822, 25 from SwM

As an aside, owners of the hanged slaves received compensation from the Executed Slave Fund into which all slave owners, free black and white, paid. After all, the state had taken away, permanently, personal property of the slave owners. Usually when the state was called on to execute a slave, the owner was paid one half of the assessed value of the slave. All southern states maintained an assessment fund for such incidents. When Ewing Bell's slave, Nat, was hanged for the murder of his wife, Bell would have been reimbursed from the Fund in the amount of half the value of the slave.[64]Southern Advocate, Oct. 1, 1857.

Freemen of color in Huntsville who owned slaves also paid into the Execution Fund. If one held ten slaves or fewer, the assessment was 1¢ for each slave; if there were between 16- and 60 in number, the assessment was 2¢ each. Their fees doubled, freedman John Robinson paid for his two slaves at 2¢ each and William Sampson, also a free man of color, paid 2¢ for his one slave.[65]Assessments 1857, 1859.

The number of free blacks actually involved in the South Carolina uprising was small, but the leader was certainly Denmark Vesey. As a result, the entire affair was linked to free blacks and the free black African Methodist Episcopal Church. Always considered suspicious, the independent African church became more of an assumed threat. All independent black churches, if they weren't already, would be suspect. South Carolina as a reward freed the slaves who reported that conspiracy. Among them the already free Negro, George Pencil, who helped expose the plot, surely understood that all free people of color had more to lose in rebellion. South Carolina, immediately considered re-enslaving its entire free colored population.[66]Richard C. Wade. "The Versey Plot: A Reconsideration," in Journal of Southern History. Vol. 30, #2 (May 1964), 143-161.

In 1830, the Alabama State Supreme Court ruled that slaves could no longer be emancipated by will. The Anti-Immigration Act of 1832 made it unlawful for any free person of color to immigrate and settle within the state. If the offender did not leave within 30 days, thirty- nine lashes might convince that free Negro to move on. If not, he could be sold into slavery for a year or even life after a third offense.

After hearing reports of a slave insurrection in 1830, Governor Moore had sent a regiment of militia to Selma only to discover it was just another rumor. Nonetheless more harsh laws were enacted. Perhaps to speed up the emigration of free blacks, in 1834 the state legislature passed an act allowing individual county court judges to emancipate slaves. Owners were required to publish in a county newspaper for at least 60 days the name and description of each slave to be freed. This information was then entered into the legal records. The master was required to give the name and description of the slave and to file a petition with a judge of the county court. After that the emancipated slave was required to leave the state. Any who might "return would be imprisoned and sold by the sheriff to the highest bidder as a slave for life."[67]Dorman, 11.

In February of 1831 (less than ten years after the South Carolina events), the Turner Rebellion caused more immediate action once the news spread from southeastern Virginia. Nat Turner, a slave known since childhood to have visions, started an uprising during a solar eclipse when he felt the time was fortuitous. He led 40-50 other slaves to kill their masters. They believed more slaves would join the cause, and their number amounted probably to about seventy. Fifty-six whites were killed, at least 55 blacks, and probably many more undocumented murders occurred. Because Turner in his childhood had been allowed to learn to read and write, whites reasoned that these events clearly justified not educating blacks.

Up until then the city fathers in Huntsville of early 1831, at the aldermen's meetings appeared only to respond to the mundane actions of its citizens. The latest ordnance was concerned about regulating behavior at the Big Spring.

"…Whereas sundry persons of the town, as well as visitors, having no regard for common decency have been in the habit of using the Bluff over the Spring as a necessary. Be it ordained, that if any person or persons shall make such use of said Bluff, he, she, or they so offending shall forfeit and pay for every such offense if a free person the sum of five dollars, one half to the use of the Corporation, the other half to the use of the informer and if a slave he, she, or they shall receive upon his or her bare back ten lashes, well laid on by the constable."[68]City Minutes, Feb. 1828-April 1832, 28, 29.

By October, when the news of the Turner Rebellion reached Huntsville, an exceedingly structured ordinance was quickly enacted for the safety of the citizens, all white of course. Some of the sections follow.

NO. 46 "An Ordinance to Establish a Night-Watch & Patrol

Be it ordained by the Mayor & Aldermen of Huntsville. That a Night-Watch and Patrol of Two discreet and vigilant persons shall be established for the purpose of guarding and patrolling the Town at night, under the following rules and regulations: viz

1st. It shall be the duty of the Watchmen to ring the Bell of the Court House at 10 oclk P. M. precisely; at which time they shall commence their tour of duty, and patrol all the streets and alleys of the Town until break of day - crying the hours and half hours, throughout the night.

2nd. It shall be their duty to arrest and [confine] in Jail, all coloured persons whether bond or free, whom they may find from their proper lodgings after the commencement of the watch: unless the watch are satisfied that they are upon business; in which case, it shall be their duty to see them to their proper quarters.

4th. It shall further be their duty to enter any inclosures or houses where then maybe an unlawful assemblage of persons of colour.

All slaves committed to Jail by the Watch under this ordinance, shall be liberated in the morning, upon their Master's paying the sum of one dollar to the Jailor: and in case of his neglect or refusal to do so, the said slave shall receive fifteen lashes upon his bare back to be inflicted by the constable, and then be discharged. All Free Person of colour, committed to Jail under this Ordinance, shall be fined at the discretion of the Mayor in a sum not exceeding Ten Dollars; and be held in custody until the same is paid."[69]Ibid.. Feb. 1828-Ap. 1832, 155-157.

And, to further secure safety for whites and punish the free colored, the next restrictive ordinance was posted. (Of course technically, because they weren't allowed to learn to write or read, a white person would have to inform the free blacks of the new ordinances and what to expect.)

NO. 47 "Ordinance Supplemental to Ordinance No. 21

Be it ordained by the Mayor and Aldermen of Huntsville, That from and after the 15th day of November next, it shall be unlawful for any Free Persons of Colour to hire a slave or keep a hired slave about his, her or their premises, under a penalty not exceeding Twenty dollars for every such offence: and the continuance thereof for one week after a recovery under this ordinance shall be considered a new offence.

And be it further Ordained, that all such Free Persons of colour so offending, shall be committed to Jail, until the fine assessed against them shall be paid."[70]Ibid., 155-157.

Colonel Bradford noted in a letter to the governor in late 1831 that Madison County was defenseless and in danger because thousands of "able bodied Negro men" could destroy Huntsville, and he though the citizenry should be armed. Therefore he asked for one hundred muskets with bayonets or else "the Town might be destroyed and many of our people slain or ruined."[71]Dupree, 218.

Close to home, an alleged slave revolt in July 1835 added to the alarms. Slaves in Madison County, Mississippi were overheard plotting a rebellion. After investigating, apparently there was common talk that the legendary outlaw, John Murrell planned widespread havoc, and slaves would be set free to roam at will. That was enough for the Huntsville Southern Advocate to print tales of weapons hidden anywhere and planned attacks everywhere. The citizens of Madison County, Alabama had organized by August and a Committee of Twenty was chosen to investigate the situation. By the end of the month a Grand Committee of 160 members divided the county into sixteen subdivisions. Each division had full power to arrest anyone suspected of insurrection, black or white. The Committee of Twenty was given the power to convict and punish. All this, of course, was vigilante action and illegal according to all laws. Again rumor arrived, this time from the northwestern district of the county that hinted at a planned insurrection. Although there was no discerned plot, the slaves were now heard talking openly about abolition. As a result rural slaves were prohibited from traveling to Huntsville where they might be led further astray with the help of the free colored people here.[72]Ibid. 217-218.

Later in 1839, Governor Bagby's message to the Assembly noted, "Considering the peculiar character of a portion of our population and looking to any emergency that might arise, I consider the organization of an efficient troop of cavalry in every county in the state as a matter of vast importance to our safety."[73]Cited in Dorman, 8-10.

These events, along with the subsequent regulations that followed signaled the beginning of the decline in number of free people of color in Alabama and within all the Deep Southern states.

There were, however, other possible alternatives for freedom. The first efforts of the American Colonization Society appeared to satisfy many needs for dealing with the free black problem. Local lawyer and one-time mayor of Huntsville, James G. Birney, a graduate of Princeton and a member of select social circles, was an agent and vigorous supporter of the ACS. A chapter was formed in Huntsville and attendance was good for a time, and even the free black community became aware of the possibility of emigration to Liberia. In the early years of the 1830s Birney traveled throughout the South promoting the cause, but he also began to have doubts as to the effectiveness of the plan which encouraged free blacks to migrate to West Africa. Part of the development by evangelicals and Quakers implied that blacks were inferior and incapable of living in American society. Hard-line Abolitionists began to have more influence, and their emphasis became emancipation. Much to the relief of many local citizens, Birney moved north and became a leader in the new political Party whose aim was abolition. He ran for President of the United States in 1844 and 1846 for the Free Soil Party.

Huntsville's Southern Advocate in 1834 echoed the feelings of Birney's former friends and neighbors. It would seem that colonization might "…elevate the black population to an exact level with the white … so hostile and opposite in every social and political aspect."[74]Southern Advocate, Aug. 19, Oct. 7, 1834. Was that the goal of Birney and the Abolitionists? Apparently so.

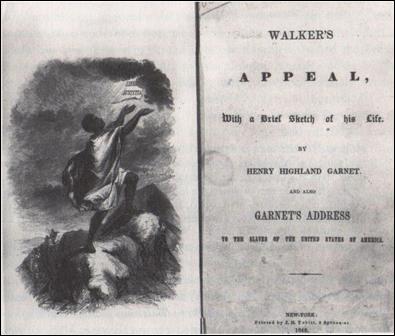

Feelings toward the Abolitionist's press were hardening within the South. David Walker, a free black migrated from North Carolina and was living in Philadelphia with other aggressive abolitionists. Adding to the flames he wrote a militant call for a slave uprising, David Walkers' Appeal, and the book was published in 1848.[75]James Oliver Horton. Free People of Color. (Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993), 37.

In 1850, as a result of Abolition talk, an unusual number of floggings were reported in the nearby Berkley community; now was not the time for slaves or free people of color to speak rashly. In town the "Sunday Police" was established to prevent any blacks from purchasing liquor at the groceries on that day.[76]James Record, A Dream Come True. Vol. I (Huntsville: James Record, 1970), 106.

Moreover, the U. S. Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 required citizens on a national scale to assist in the recovery of fugitive slaves. Cases could be brought before special commissioners who would be paid $5 if an alleged fugitive were released and $10 if he or she were sent away with the claimant. Thus Southern slave owners could reclaim their "property" in the form of runaway slaves, with the assistance of local or federal forces. Free people of color living in Northern states, even for many years, were suddenly arrested and conveyed back to former Southern owners or dealers in slaves. Local law enforcement officers and citizens who refused to help, or actively hindered the re-enslavement were subject to large fines and even prison. This legislation easily led to theft of any person of color.

By now if they did not already have papers, free blacks needed to obtain legal proof of freedom and to carry certificates of freedom attested to by competent witnesses at the county court to confirm they were permitted to live there. Failure resulted in a fine of $200 or being "hired out by the sheriff" to cover the cost of the fine.[77]West, 27.

The free papers of Isaac Clem [Clemens] reflect the harshness of the times with the description of his scars and missing fingers. Included is the information that he was free and

"known to three men since infancy, now about 26 or 27, black or dark complexion, 5' 7" or 8", all the fingers of his left hand are off, except the forefinger and it is of but little service, the thumb is perfect, also a scar on right side of his face, in front of the ear, also a scar just over the left eye, one on the left cheek and also one on the left side of the chin or jaw, his left also has been broken. Isaac Clem is a son of a free woman of color, now deceased whose name was Lavisa Finley, generally called "free Lavisa."

Isaac was born in the vicinity of Huntsville where his mother lived for many years. His witnesses included C.D. Kavanaugh (a former sheriff), William Robinson (a former sheriff), Joseph Ward, Alexander Erskine, F.H. Newman, John W. Jones and William Acklin - all prominent men about town.[78]Deed Book Y, 537. (See Jane Finley in Appendix II for other remarkable familial connections.)

The Gainesville Independent on March 13, 1857 noted, "Free Negroes were dangerous as they fell an easy prey to designing men; to permit them to remain in a slave state was the offspring of a sickly sentimentality."[80]Cited in Dorman, 18. Certainly the complexities of being free and black, dictated the need for a cautious lifestyle.

In order to limit contact between slaves and free people of color, it became illegal for freemen in Madison County to buy or sell slaves without the owner's permission, to keep a tavern, or sell spirits. The first offense was a $25 fine and the second 25 lashes. One could not visit slaves or receive them in their homes, visit, or preach without five whites at their assembly without permission.[81]Sellers, 363. Free blacks might corrupt or lead astray their enslaved brethren.

A major national event transpired in 1857, when Dred Scott unsuccessfully sued for his freedom and that of his wife and two daughters in 1857, claiming they had lived with their master where slavery was illegal. The 7-2 decision by the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that no one of African ancestry could claim American citizenship. Blacks were "not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word 'citizens' in the Constitution." If the news had circulated locally here, and surely it did, some might remember that Dred Scott, know then as Peter Blow, had been enslaved on a plantation site nearby, currently located on the campus of Oakwood University.

Even more restrictive by 1859, the Alabama Assembly declared void all wills which emancipated slaves and prohibited removal of slaves from Alabama for the purpose of emancipation. Finally the Alabama Legislature prohibited manumissions of slaves in 1860.

It is easy to see why white labor watched with antagonistic competition from free blacks. By accepting lower wages and longer hours, many free Negros found employment, but often at the cost of performing jobs white workers found distasteful. And to work along side blacks was demeaning to most whites. They often lived and worked under conditions white workers would not accept.

Hired slaves were considered by white citizens as necessary, but not to be trusted. Huntsville, as most towns did, maintained slaves for street work who, when not working, might be hired out by the city (the Muscle Shoals Canal, for example, required a vast number of workers). Always on the watch, the white community perceived freemen and hired slaves both to be thieves and disorderly when given the chance. The Southern Advocate suggested they were "a thievish, idle and worthless class of society."[82]Dupree, 218.

Although most successful freemen earned their living serving whites, some free Negroes ran boarding houses for other free Negroes and slaves whose owners allowed them to live on their own and hire out. They ran cook shops and grocery stores tucked away in alleys and basements, which might also serve as saloons with illegal liquor and unlawful gambling - places not visited in the daily lives of most white citizens.

It was not unusual for free blacks to, from time to time, hire other Negros in one capacity or another. "Jacob Wilson, a free man of color, appeared before the Board, petitioned for leave to hire Judy Spence within the corporation limits in 1834.[83]Ibid, 214. There are countless individual instances of this in the following appendices.

Appendices"History is what is written and can be found; what isn't saved is lost, sunken and rotted, eaten by earth." - Jill Lepore, Historian

The material here, as in this paper, is only intended to identify free people of color in Madison County, Alabama.

Appendix I shows, alphabetically, the combined census years from 1830 through 1860. Unfortunately, the census reflects the population only every ten years. The data is as good as the information given, recorded, and later transcribed. During the intervening ten years people married and changed their name, died, moved on, or perhaps were just hiding from the representative of the government. Southern law assumed all blacks to be slaves and available for arrest, it would not be unreasonable to hide from the census taker as he came along.

Appendix II shows the Huntsville census of 1865.

National Archives, M-1960, Roll 19 at Heritage Room of HPL.

Please note that the raw data appears exactly as it does in the original document.

Appendix III consists of additional material found in the records of the Alabama State Assembly (Legislature) and in Madison County court records. Many of these names are also in the Federal Censuses; many are not. There will only be a very few marriage records and death dates and fewer birth records. Of those required by their manumission to leave the area, there will be little more to be learned here. This section is a combination of Madison County, Alabama newspapers; court records of land ownership; personal property assessments; poll tax assessments; deed books; Probate Court; Circuit Court; Chancery Court; Orphans' Court records; Minutes of the Commissioners Court; County Minute Book, Superior Court of Law and Equity, Mississippi Territory, Madison County; 1850 and 1860 Alabama Mortality Schedule; 1850 and 1860 Federal Agricultural and Manufacturing Censuses; Huntsville Aldermen's Minutes; Freedmen's Census of Huntsville, 1865; and Southern Claims Commission, Approved and Rejected. The Freedmen's Bank incorporated by Congress in March 1865 maintained an office here with records that included information about the members and their families. (Some very few uncertain identities as Jones and Johnson were omitted.)

The sources are listed after the individual entry in brackets [ ] to avoid copious citations. These free people of color, who during their lives carefully maintained a balance between black and white, at least now most had surnames. Even so, unfortunately some of the legal records only reveal the surname of the master and not the emancipated slave. Some have no surnames.