From The Historic Huntsville Quarterly of Local Architecture & Preservation, Spring, 1994, Volume XX, No. 1.

When William Henry Burritt died in 1955, he ended a branch of the Burritt family in America which had spanned 325 years and eight generations. His forefathers had invested their hard work and their knowledge of the land to offer future generations the benefits of their labors. The legacy of their efforts was advanced by each successive generation. The diverse profiles of the clerics, educators, soldiers, politicians and physicians that comprise the Burritt family represent the average individual contributions that shaped and preserved our nation.

Their legacy began sometime prior to 1635, when William Burritt and his wife Elizabeth emigrated from Glenmorganshire, Wales and settled in Stratford, Connecticut. The exact date of their arrival is unknown. The only place where William Burritt's name appears prior to the inventory of his estate, dated January 15, 1650 or 1651, is in the memorandum of the number of rods of fence for the community and the share each settler would build. In the schedule of his estate, dated 1651, he is spoken of as "lately deceased." The amount of the inventory was 140, a very modest estate to support Elizabeth and her three children: Stephen, John and Mary.

Elizabeth Burritt was a frugal and discerning woman, controlling her own affairs and ordering her household welL Apparently not able to write her name, she made her mark all over the early town records. Before her death in 1681, she substantially added to her possessions, purchasing more land than she sold. On April 5, 1675, she appointed considerable real estate to her sons by conveyances as follows:

"To my loving and dutiful son, John Burritt, of ye said place, an equal half of my whole accommodations in Stratford aforesaid, being ye allotment and interest of my deceased husband, Wm. Burritt, or by procurement of myself and my children, excepting only ye home and parcel of land at ye Fresh Pond, in ye old field, ye which has already been contracted to Stephen."[1]The Burritt Family in America.

Stephen Burritt, the eldest son, was in the list of Freemen at Stratford "8th month, 7th day 1669," and a lot owner in 1671. Over the next twenty-six years, Stephen would hold increasingly important roles in his community. In 1622, he was confirmed by the General court as Ensign of the Train Band and appointed Lieutenant on January 17, 1675. That same year the Council at Hartford ordered Stephen Burritt to lead the Dragoons from Lairfield County to Norwottag and join Major Robert Treat "in defense of the plantations up the river, and to kill and destroy all such Indian enemies as should assault them on the aforesaid plantations." Stephen's courage and resourcefulness as an Indian fighter led the council of the colony to appoint him as Commissary of the army on November 23, 1675. He was not only a brave soldier, the town records also give evidence that he was involved in local governmental affairs. At the town meeting held January 1, 1673, he was chosen Recorder. In 1689, he was appointed on a committee to assess damages for changing of Black Creek into Mall River. The same year he was also chosen one of the Townsmen and the chairman of the committee on killing wolves.[2]The Family of Blackleach Burritt, Alice Burritt, Washington D.C.: Press of Gibson Brothers, 1911, p.9.

His political and military successes were crowned by his marriage to Sarah Nichols, November 8, 1673. Sarah was the daughter of Issac Nichols of a prominent Stratford family. By this marriage, Stephen had seven children: Elizabeth (July 1, 1675); William (March 29, 1677); Peleg (October 5, 1679); Josiah (1681); Israel (1687); Charles (1690) and Ephraim (1693).

Little is known about Peleg Burritt. He married Sarah Bennett, daughter of James Bennett on December 5, 1705. Records inform us that they had four children: William, baptized October 13, 1706; Daniel, 1708; Sarah, born July 20, 1712; and Peleg (Jr.) born January 8, 1720 or 1721. Peleg Burritt, Jr. established his homestead near Ripon Parish. He married Elizabeth, daughter of Richard Blackleach, Jr. Peleg and Elizabeth had two children Mahitabel and Blackleach before Elizabeth's death in 1744.[3]Ibid., p. 11.

Peleg Burritt, Jr. remarried on Thanksgiving day, 1746, to Deborah Beardsley. Through this union they had six children: Stephen (1750), Joel, Mabel, Gideon, Sarah and Mary.

At the age of nine Blackleach, Peleg's first son, inherited a sizable estate from his grandfather, Richard Blackleach, Jr. His executors, Ephriam Judson and Daniel Thompson, were given the authority to sell land on Fawn Hill if necessary to pay debts and bequests. Judson and Thompson sold the lands to Peleg Burritt Jr. on March 5, 1753. The total inventory of the estate awarded Blackleach was 1,051 pounds 3 shillings and 7 ducats of which 850 was real estate.

Nothing notable is known about Blackleach's boyhood until he entered Yale, where he graduated in the class of 1765. While at Yale he heard Rev. Whitfield deliver a memorable discourse in the college chapel, which is said to have led Blackleach to unite with the church in Yale College on February 3, 1765.

Upon graduation from Yale, Blackleach pursued his theological studies under Rev. Jebediah Mills of Ripton Parish. Ordained February 22, 1768, he received his first formal call on June 15, 1744, from the congregation at Pound Ridge, in Westchester County, New York. Rev. Burritt was a zealous Whig during the Revolutionary War, often carrying his patriotism into his pulpit.

Family history records that Rev. Burritt often "took his musket into the pulpit for defense, and if need be, for ready joining in offensive warfare." It is not surprising that his outspoken patriotism would lead to his eventual arrest on June 23, 1779. The Rivington's Royal Gazette records a raid:

Some days ago a party of Rebels came over to Treadwell's farm, Long Island, conducted by James Brush, and carried off Justice Hewlett and Captain Young -- since which the refugees went over to Greenwich in Connecticut and returned with 13 prisoners, among who is a Presbyterian Parson named Burritt, an egregious rebel who has frequently taken arms, and is of great repute in the colony.[4]Ibid., p. 13.

Captured and taken prisoner from his bed Blackleach was transported to the notorious Sugar House Prison in New York. Soon after the capture, his wife Martha Welles and their eight children fled to friends at Point Ridge who cared for the family during his imprisonment. Mr. William Living discovered Rev. Burritt in prison and recounted his condition as "very low with prison fever, in his miserable cell." Mr. Living used his influence to remove him to a suitable place for medical treatment and looked after him each day. Fourteen months after his imprisonment, Mr. Living was able to secure his release through an exchange of prisoners.

Upon Rev. Blackleach's death on August 27, 1792, he left twelve heirs with his first wife Martha Welles: Eunice (1766); Melissa (February 26, 1768); Martha (October, 1770); Sarah (January 29, 1771); Ely (March 12, 1773); Gideon (September 15, 1774); Diantha (January 9, 1776); Rufus (1777); Blackleach (October 29,1779); Prudence (November 2, 1782); Samuel (March 5, 1784) and Susanna (March, 1785). Martha Burritt died in April, 1786, just six weeks after the birth of Susanna. Blackleach, challenged by the needs of so many young children would remarry sometime prior to 1790 to Deborah Welles. They would have two children before Blackleach's death, Deborah (1790) and Selah Welles (1791).[5]Ibid., p. 15.

Ely Burritt was the eldest son of Rev. Blackleach Burritt. Born at Pond Ridge, March 12, 1773, Ely graduated from Williams College in the class of 1800. He obtained his license to practice medicine at Troy, New York, March 29, 1802, and quickly gained recognition for his medical skills. Dr. Wayland, who studied medicine with Ely, said:

Dr. Burritt was a man of remarkable logical powers, of enthusiastic love of his profession, and of great and deserved confidence in his own judgement. He stood at the head of his profession in Troy, and in the neighboring region, and was a person of high moral character.

His brother Rufus joined his practice shortly after Ely obtained his license to practice in 1802. He studied medicine under Ely's watchful instruction and was admitted to practice in 1806. Shortly after 1814, Amatus Robbins, a fellow graduate of Williams College, also joined Ely's practice. Dr. Robbins would continue as a pupil and partner to Ely until the death of Dr. Burritt in 1823. Upon his death, Amatus assumed the extensive practice and on September, 1828, married Julia Ann Burritt, the daughter of his former partner.[6]Obituary of Amatus Robbins, printed pamphlet, author unknown, Burritt Collection, Burritt Museum and Park.

Ely's devotion to medicine was carried on by one of his sons, Alexander Hamilton Burritt, born in Troy, New York, on April 27, 1798. Alexander studied medicine with his father in addition to enrolling in the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York. He graduated in the spring of 1827, and opened his allopathic practice in Troy, New York, that same year.

In 1838, Alexander was invited to examine the practice of his cousin Dr. John F. Gray and his partner Dr. Hall. Dr. Gray had recently embraced a new system of diagnosis and treatment called Homeopathy. Homeopathy had been developed by a German physician, Samuel Hahnemann (1755-1843),' and was introduced into the United States in 1825.

Homeopathic thought differed from allopathy primarily in its method for ascertaining the significant factors in diseases and in remedies. The cornerstone of Hahnemann's system was the "law of similars." Hahnemann described the "law of similars," in his book The Oranon of Medicine as follows:

Each individual case of disease is most surely, radically, rapidly and permanently annihilated and removed only by a medicine capable of producing (in the human system) in the most similar and complete manner to totality of (the disease) symptoms which at the same time are stronger than the disease.[7]Samuel Hahnemann, The Organon of Medicine, Translated with Preface by William Boericke, Calcutta: Roysign and Co., 1962. Section 28.

The success of this system experienced by Dr. Gray and a growing public interest in the practice convinced Alexander to adopt the system in 1838. He opened his homeopathic practice in Crawford County, Pennsylvania. Afterwards, he relocated to Cleveland, Ohio, where he aided in the organization of the Western Homeopathic College in 1850. While at the College, he served as Vice President and Professor of Obstetrics until ill health forced his resignation in 1854. Following his resignation, he settled in New Orleans, Louisiana.

The 1860 City Directory listed both his residence and office in the French Quarter at 17 Rampart Street. The Directory also lists a Mrs. Frances Burritt, M.D. (Homeopathic) at that address, however her relationship to Alexander is unknown. The Directory informs us that her practice was limited to the "special attention to diseases of women and children" and her office was at 92 Melpomese. Alexander would continue to practice homeopathic medicine in New Orleans until his death at age 78, on August 22, 1876.

Alexander was survived by two sons, Ely and Amatus. The later was born in 1833. Amatus is presumed to have studied medicine with his father, graduating from the Western Homeopathic College in 1853. Upon graduation it is thought that he traveled to Indiana and then Illinois before establishing a medical practice in Huntsville, Alabama, in 1855. He established his office on the south side of the Courthouse Square with Dr. Richard Angell. The exact date he opened his practice is unknown, however, his certificate to practice medicine was issued on November 11, 1855, by the Homeopathic Medical Board of Alabama.[8]Homeopathic Medical Board of Alabama, Certificate to Practice Medicine, issued to Amatus Robbins Burritt, Burritt Collection, Burritt Museum and Park.

It is not known how the Union occupation of Huntsville throughout most of the Civil War affected Amatus' practice. Records of his activities during the war are clouded. Family histories state that Amatus remained neutral and served as a mediator between the opposing sides during the occupation. A published account of the Burritt family history in America, dated 1892, recorded that Amatus served briefly in the Confederate Army while his only brother, Ely, was in the Union Army. The account outlines that Ely was taken prisoner, and Amatus was instrumental in obtaining his release. No documentary evidence has been uncovered to substantiate either of these family historical accounts.

In 1866, Amatus married Mary King Robinson, the daughter of a prominent Madison County plantation owner. Amatus and Mary settled across the street from the Church of Nativity on Eustis Street and raised two children: Carrie Boardman (April, 1867) and William Henry (February 17, 1869).

Cancer deprived Amatus of assisting his children to reach their potential. On August 23, 1876, his painful illness ended his life. An obituary published in the Huntsville newspapers lamented:

It is a sad, but not surprising announcement of the death of this truly excellent citizen and popular physician, Dr. Amatus Robbins Burritt has been expected for some months past. He died at 10 o'clock on Tuesday night last at his residence in this city in the 43d year of his age, after lingering for many months with the fatal disease cancer. He tried the skill of the physicians of St. Louis and New York and also the baths of the Hot Springs, but none of these could give him relief. He continually grew worse until death released him from his intense sufferings. The entire city of Huntsville mourns the loss of Dr. A. R. Burritt and sincerely sympathize with the bereaved family.

Dr. B. had been a citizen of Huntsville for about 23 years, and during the whole time of his residence here he enjoyed the esteem and confidence of his fellow cidzeus [sic]. His practice was large and he was much beloved by his patrons. His place will be hard to fill. We do not know that we ever announced a death with more sincere regret.[9]Obituary of Amatus Robbins Burritt, Newspaper clipping, August 876, unidentified paper, Burritt Collection, Burritt Museum and Park.

The proceedings of the meeting of Physicians and Druggists held August 24, 1876, record the lengthy eulogy of Dr. Burritt presented by Dr. A. R. Erskine, Chairman who remarked that Amatus began:

... his career with us at an early age he very soon developed what a few men of his years could boast of, rare, skilled and professional knowledge. By intuition, as it were, he read character, as well as disease and while he was ever quick in the formation of his judgement, which was oftener correct, he was equally quick in the selection of the appropriate remedy, and prompt to alleviate the sufferings of his patrons. Always courteous towards his brother Physicians, he was ever fair and strictly honorable in acting out the professional code. A man of large heart, he possessed a broad charity, and was ever ready to dispense it to the poor and needy ...[10]"Proceeding of the Meeting of Physicians and Druggists" Newspaper clipping, August 1876, unidentified paper, Burritt Collection, Burritt Museum and Park.

On behalf of the Druggists of Huntsville, Dr. J.C. Spotwood submitted the following:

For twenty-two years Dr. Burritt practiced his profession in our city, and by his skill, indomitable will and energy, overlapped almost every barrier of prejudice and attained high distinction to all his duties ...[11]Ibid.

Amatus' widow, Mary King Burritt, did her best to maintain her family's life-style. The 1880's census of Madison County records the Burritt family living on Eustis Street, Ward 3 and lists the residents, M.K. Burritt age 32, profession - housekeeping, Carrie B., age 13, at school and William Henry, age 11 at school.

Little is known about the children's education. It is known that William Henry attended college at Brigham, North Carolina and graduated from Vanderbilt Medical School, Nashville, Tennessee, in 1890. His education at Vanderbilt was followed by post-graduate work at Pulte Medical College in Cincinnati, Ohio, and the Lying-In Hospital, New York City.[12]Biography of William Henry Burritt, Citizens Historical Association, Indianapolis, Indiana, No. B999 Dl E45 F13, February 5, 1938, Historical Collection, Huntsville Public Library, Huntsville, Alabama.

His mother's failing health caused him to return to Huntsville early in January, 1891. Mary King's apparent mental illness led Dr. Burritt to petition, on February 12th for the recognition of his mother as a non-compus-mentis. His appeal, supported by the testifying signatures of fourteen friends and relatives, was approved on February 21, 1891. The cause of Mary's insanity was not revealed. Records show that she was committed to the State Asylum, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and remained so until her death in 1923.

William made every effort to settle into Huntsville society by the late summer of 1891. He was a member of a small social group called the "Chimpanzee Club." The members of the club each sported a pin made out of a ten cent piece with a chimpanzee carved on one side. The club was formed to enjoy each other's company through evenings of polite social conversation, dinner and occasionally chamber recitals and theater productions. Members of the club included Misses Irma Gray Ridley, Belle Darwin, Lilla Turner, Annie Curry, Liela Cole and Messrs. Anderson, Sheplor, Price, Simmons and Burritt.[13]"Chimpanzee Club," Newspaper Clipping and photograph, Burritt Collection, Burritt Museum and Park.

Dr. Burritt's involvement with the Chimpanzee Club was brief however; for he quickly met and courted Miss Pearl Budd Johnson whom he married on November 16, 1892, in St. Johns Cathedral, Denver, Colorado. Pearl was one of four children of Captain James R. Johnson and Laura B. Johnson of Cincinnati, Ohio. Capt. Johnson was a Union officer in the 4th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry and was part of the occupying army that seized Huntsville in 1862, under the command of General Mitchell. Capt. Johnson became infamous in the area when he captured the Confederate flag of the Huntsville Guards, in a skirmish just north of the Whitesburg Bridge as the Guards made a hasty retreat over Green Mountain. The beautiful handmade flag had been presented by the ladies of Huntsville just the day before to the Guards and the loss added to the insult of the day. Capt. Johnson sent the flag home where it stayed until his daughter Pearl returned it to Huntsville and displayed it at the Presbyterian Church in May of 1895.

Like many of the occupying officers, Capt. Johnson had fallen in love with the city during the Civil War and had made many friends among the citizens. After the war he returned to Cincinnati and engaged in business but never forgot the beauty of the Tennessee Valley. In 1891, Capt. Johnson brought his family for a visit to Huntsville, his arrival recorded in the Huntsville Weekly Democrat on July 29th:

Mr. James R. Johnson, of Cincinnati, with his wife and daughter, are guests of Mr. J. D. Chadwick. We understand that Mr. Johnson contemplates settling in our city. His attractive daughter will be a welcome acquisition to our social circles.[14]Huntsville Weekly Democrat, July 29, 1891.

They stayed in Huntsville until late in September and then returned to Cincinnati. No record has been found as to when the family settled in Huntsville; however, the 1900 census for Madison County lists Mr. and Mrs. Johnson and their son, Richard, renting a home on Franklin Street.

It is not known if William met Pearl in Huntsville or while he was practicing medicine at the Pulte Medical College in Cincinnati, Ohio. Whichever the case, William and Pearl were married in Denver, Colorado, where Pearl's father had relocated the family while he recovered from consumption.

Little is known about their marriage except for Pearl's brief diary entries. In her journal the seventeen year old bride reveals her deep and abiding love for her "dearest sweet Willie." Their marriage began with a four day honeymoon on the train from Denver to Huntsville. Upon their arrival the young couple took rooms in the home of Mr. Henry Turner on Eustis Street.

In 1893, Dr. Burritt became interested in the Hagey Institute for Drug Abuse and became a shareholder in its patented program. His interest in the program led him to serve briefly as the physician-in-residence at the Hagey Institute in Waco, Texas. While there he received a letter from Mr. A. C. Hill requesting him to become the physician-in-charge at the Institute. There are no records to document his acceptance of this position.

From 1894 until 1897, Dr. Burritt made several attempts at acquiring certification by the Alabama Medical Association. Tensions between allopathic and homeopathic thought might have contributed to Dr. Burritt's rejection until June, 1897. The announcement of the certification was recorded in the 1898 annual Transactions of the Medical Association, the State of Alabama. In 1899, the Transactions listed him as a practicing "Homeopathic Physician." However, he was extended a membership in the society.

With his certification by the State, Dr. Burritt set about to establish his practice. The success of his efforts were clouded by the tragic death of Pearl on July 3, 1898, at the age of 23, from complications following surgery. The Church of Nativity records list the cause of death from appendicitis surgery.

Dr. Burritt's family had long been plagued with insanity. In addition to his mother, two of his uncles, his sister and his only nephew had been committed due to mental instability. Unsure of the cause, Dr. Burritt had lived in desperate fear of passing the illness on to his off-spring. Whatever the cause, Pearl's untimely death haunted Dr. Burritt and left him burdened with grief. Years later he continued to express to friends the depth of his loss of Pearl.

In the year that followed Pearl's death Dr. Burritt met Mrs. Josephine T. Drummond. Mrs. Drummond was the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. E. M. Hazard of Alton, Illinois. She was the widow of James T. Drummond whom she had married as he was nearing the end of an amazing life. He was the embodiment of the American dream. He went into to the tobacco business as a book-keeper in 1862. By 1864, his business skills led to a partnership with Meyers and by 1879, he was sole owner of the Drummond Tobacco Company with a capital stock of $100,000 producing three million pounds of plug tobacco a year. By 1880, the firm had grown to employ over 1500 workers. His business triumph won him a political career which culminated in four successive terms as Mayor of the City of St. Louis between 1867 and 1872. When James died in September 30, 1897, he left his formidable estate to his wife Josephine and his four children, Harrison I., James T., Charles R. and Rachel Lee Drummond.

In the summer of 1899, Josephine arrived in Huntsville to call upon her cousins the Landman's. While visiting she came down with dysentery and Mr. Landman called upon Dr. Burritt to treat her. Though twenty years older than Dr. Burritt, she fell in love with him. In a note to Dr. Burritt dated July 4, 1899, Josephine expresses her deepest sorrow for not being able to comfort Dr. Burritt in his time of sorrow. She had just learned of his loss the year hence of his dear wife Pearl. She went on to say that it too was a time of sorrow for her as well. Ten years before on July 4, 1888, she had witnessed the burning of a child from fireworks. She had rushed to the child's aid and put out the flames but in the process had endangered her own life and lost the life of the baby she was carrying.

Over the next few months their friendship grew and by the early fall of 1899, Josephine flamboyantly proposed to Dr. Burritt. After three brief months of courtship, the couple was married on November 28, 1899, at S1. Peters Episcopal Church, on Lindell Boulevard in S1. Louis, by Bishop Short. A newspaper clipping records that:

The bride wore a stylish gown of sea-blue broadcloth trimmed in very handsome lace and a shaded blue velvet hat with full veils in the pastel shades of pink and lavender. Messrs. W.P. Hazzard, E.H. Gorse and Harry E. Wagoner preceded the nuptial pair up the aisle as Mr. Calloway, organist of the church, played the bridal chorus.[15]Unidentified newspaper clipping, St. Louis Scrapbook, St. Louis Historical Society, St. Louis, Missouri.

The newlyweds briefly lived in Huntsville while Dr. Burritt completed his tenure as Health Officer of Madison County and then moved to S1. Louis, Missouri, where they resided in the Drummond mansion located in 3631 Delmar Boulevard.

In St. Louis, Dr. Burritt shifted his attention from medicine to the manufacture of rubber products. From 1903 to 1927 Dr. Burritt patented numerous tire inventions in the United States, Canada and Europe. In addition, his business ventures included the management of several farm and logging interests in Alabama and the Drummond mining holdings in the Dakotas and California. The Burritts remained. in St. Louis until Josephine's death on March 6, 1933. Her estate upon her death was valued at $295,437, the bulk of which she left to her husband.

Following Josephine's death, Dr. Burritt returned to Huntsville. By March, 1934, he began plans for building his retirement house, farm and goat dairy. To many persons' surprise he selected the 167 acre site atop Round Top Mountain overlooking Huntsville and the Tennessee River valley. Those who knew him thought the site suited him perfectly.

The mountain had always been a favorite boyhood haunt. As a young man he had spent many summers enjoying the refreshing breezes and the cold limestone springs of Monte Sano. Like many prominent Huntsvillians, the Burritt's owned a summer cottage in the Monte Sano community of Viduta. Here the family would retreat from the heat and summer illnesses that plagued the valley. Their stay frequently lasted the "season" from June 1st through October 1 st. Fond memories of those carefree summers and his belief as a homeopathist that fresh air, sunlight and clear spring water would sustain his health made the selection of the mountain site perfect.

Construction of the 14 room mansion began early in the fall of 1934 and would continue until its completion 22 months later. On June 6, 1936, Dr. Burritt began to move into the house. Before the day was over the house would be lost due to faulty wiring and the ensuing electrical fire that completely destroyed the structure and all its contents. Valley residents would recount years later that the fire could be seen allover the valley and "looked like Mount Vesuvius."

At age 66 many men would have given up; however, encouraged by friends Dr. Burritt began plans for the second house. It was during the reconstruction of his house that he married Alta F. Jacks, on May 20, 1937. They returned from their honeymoon to live in the top three rooms of the mansion, while the first floor was completed.

Their marriage was brief, ending in divorce in the mid 1940's. Alone, Dr. Burritt would live his remaining years in the mansion with the assistance of a housekeeper and a grounds caretaker until his death in 1955 at the age of 86.

Having no heirs, he left the mansion and the surrounding 167 acres to the City of Huntsville to become the city's first museum and its second largest public park.

In 1934, Dr. Burritt returned to Huntsville from St. Louis to build a house and operate a small farm and dairy. He chose to return to one of his favorite boyhood haunts - a small lush green mountain called Round Top situated south of Monte Sano. The site had never been settled. Its steep slopes were crisscrossed with old wagon roads which aided miners and timber haulers to profit from its coal, sandstone, limestone and cedar breaks. On the southern face of the mountain wound a rocky steep path, which until the development of the Florida Short Route (now Governor's Drive-US Highway 431), was the only road connecting the farms in the northern end of Big Cove with Huntsville. The rocky roadway was constructed in the 1840's and was called the Big Cove Turnpike. The four-mile roadway holds a rich history of hijacks and hold-ups as well as the dubious honor of being the site of the surrender of 100 Confederate irregulars on May 5th, 1865, signaling the end of the fighting in Madison County.

It is likely that Johnathan Broad used the turnpike to haul coal to Huntsville markets from three mines he opened on Round Top in the 1850's and operated until the 1870's. In addition to the mines, the mountain slopes are dotted with small pocket quarries where the City of Huntsville harvested sandstone in the 1870's and 1880's to build the city jail and lay downtown sidewalks.

The top of the mountain was crowned with approximately 18 acres of level land with rich sandy loam suitable for the development of a small farm. When Dr. Burritt visited the site in late August, 1934, he walked the mountain and selected a location for his house on the western bluff overlooking the Tennessee River valley and the city of Huntsville.

The purchase of 160 acres of land on Monte Sano by Dr. W.H. Burritt.was disclosed today ...

It is definitely understood that Dr. Burritt, a member of a prominent early family of this county, plans to build a home on Round Top and to settle there permanently. He has written that he will arrive here from St. Louis the last of the month or the first part of October to begin preparations ...

This property formerly was owned by the Monte Sano Development Co., as a part of the tract which it planned to develop at the southern end of the mountain [Monte Sano].

No settlement was started on Round Top, however, and so far as can be learned from reliable information, none has ever been located there.[16]Huntsville Times, September 6, 1934, p.6.

Burritt chose to capitalize on the the old trails that led to the stone quarries to build a road leading to his house site. Excavation of the 1/2 mile roadway from the newly constructed Monte Sano Boulevard to the top of the mountain began April, 1935, under the direction of Cardney Gardiner and Roy Stone with the aid of twelve men.

By August, a caretaker's quarters was built near the bluff, which Dr. Burritt occupied while the mansion was under construction. Three-quarters of the foundation had been blasted out of the rock and workers were selecting sandstone for the construction of five chimneys. Fifteen men were working on the construction of the fireplaces when Mr. George H. Walters, of New York, was hired to take over the direction of the construction project.

By late September, the framing of the walls began and the unusual shape of the house began to unfold. Those who visited the site marveled at the floor plan of the house. It was laid out in the shape of an X or as Dr. Burritt called it a "maltese cross. II The center of the structure contained a two story core comprised of an entrance hall, staircase and dining room on the first floor and a sitting room, bedroom and kitchenette on the second floor.

Radiating from the central core were four single story wings. The two on the south side of the house featured a bedroom, sitting room and hall and on the north side a kitchen wing, with a butler's pantry and cook's quarters. The remaining wing held a formal parlor. Along the rear of the house overlooking the farm fields was a screened in conservatory. To the north of the conservatory was a cistern. Beneath the house was a garage and basement cut directly out of the rock.

Many people asked Dr. Burritt why he built such an unusual structure. His answers varied. It is likely that he designed the house to capitalize on the mountain breezes and wonderful vistas. As a homeopathic physician, Dr. Burritt placed great value in the importance of fresh air and light in maintaining a person's health and supporting a long life. Each room featured large windows designed to allow large amounts of natural light into each room throughout the day and capture the prevalent breezes.

As the winter months settled the crew began to work on the interior of the structure. One of the most unusual aspects of the interior was Dr. Burritt's use of bales of wheat straw as both insulation and structural support for the interior walls.

From his own farm experience he knew dry straw would neither rot nor mildew. Packed tightly the bales would effectively insulate against hot and cold.

In an interview from the 1950's Dr. Burritt stated that while walking across a Missouri farm he took a break from the sweltering 112 degree heat.

[He] sat down in the shade of a large heap of straw and to his entire satisfaction shortly felt much better. In a few minutes he was comfortably cool, arose and started walking again.[17]Newspaper Clipping, Publisher and date unknown, Burritt Collection, Burritt Museum and Park.

This experience led to the idea of incorporating the use of straw to build his house on Round Top. According to an article in The Atlanta Journal and Constitution Magazine in November, 1951, he stated that the:

most outstanding feature of his home is the natural air-conditioning system created by the straw walls .. .Its year round temperatures usually range between 65 and 75 degrees ... When people find out how comfortable straw houses are they won't want to live in any other kind.[18]"He Lives in a Southern Mansion Built of Straw," The Atlanta Journal and Constitution Magazine, November 4, 1951.

As odd as his idea of hay insulation sounds, the use of straw bales for the construction of shelters has its roots in America's pioneer heritage dating back to the mid 1800's. The first hay baling machine was developed in 1854. By the 1860's, diary accounts from New York record the use of bales of straw to build ice fishing shelters.

Though temporary in nature these simple shelters might have served as prototypes for bale structures that appeared on the plains of Nebraska and Kansas from the 1880's until the 1930's. Early pioneers of the plain states were forced to be innovative to overcome the scarcity of wood. Many settlers chose to use slabs of sod to build their houses. Sod construction had several structural limitations, were not very durable and required constant maintenance. The maintenance

factor might have led to the common use of straw bales in the construction of public buildings such as schools and churches. Diaries and pioneer recollections record that the only enemy of straw structures was free ranging cattle which occasionally grazed freely on the structures.

Photographs in the Nebraska Historical Society archives document numerous bale structures. Most were built in the 1880's and 1890's.

Diary accounts sometimes refer to these modest structures as flea houses because they were often insect infested. A common feature of these buildings is the use of a large overhanging roof eaves and the application of mud plaster on the exterior walls. One such bale structure still stands in Nebraska dating from 1902.

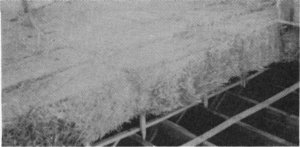

Unlike the bale structures of Nebraska, Dr. Burritt's bale walls did not bear the load of the roof system. The bales however did support the interior walls and ceilings. Once the mansion's exterior walls and roof were completed the crew began installing the bales of straw in the interior of the mansion. The wheat straw was baled in the fall and was harvested from Aaron Fleming's farm (now the Lily Flag area). Two thousand two hundred bales of wheat straw were delivered to the construction site. The bales were 18x20 inches with four wires used to bind the straw together. Dr. Burritt said when looking them over, "the bales of hay looked like giant bricks all in a row."[19]Handwritten notes of H. Merrill, Burritt Collection, Burritt Museum and Park.

An article in the Huntsville Times dated December 1, 1935, reported:

Crews there [Burritt Mansion] yesterday were placing straw in the walls of the wings, in readiness for the plasterers. The entire building will be encased in straw ... [and] loose straw ... was used for insulation between the concrete foundations and the sub-floor.[20]Huntsville Times, December 1,1935, p. 1.

By trial and error the crew developed a satisfactory method of applying a "Scratch" coat of plaster's mud on each bale of straw before it was set into place. Wooden stakes were then driven through these bales and the projecting ends were nailed to wooden rafters and the stud framework. Workman also placed stakes diagonally in the ends of adjoining bales. The bales suspended were then tied together with a network of bailing wire. Once in place they were covered by one to three inches of plaster. It is estimated that 20 tons of straw were used in the construction of the house.[21]"Fire Razes Home Built by Burritt On Mountain Top," Huntsville Times, June 7, 1936, p. 7.

On June 6, 1936, the construction work was completed, and Dr. Burritt began to move his possessions into the house. Around 2:00 p.m. workers smelled smoke and an electrical short was discovered, unfortunately not before the fire had spread too far. By 2:30 the house was engulfed in flames. Lacking sufficient water and equipment, people stood and watched the fire destroy the structure. The house burned for eleven hours, and the flames were seen throughout the county.

Dr. Burritt would tell Pat Jones, a reporter for the Huntsville Times:

The two things I was the proudest of caused its downfall. I got power up here, so I could have electric lights. Then I had the basement lined with metal to keep rats from getting up into the hay. The electricity and the metal lining combined in a short circuit to make the spark that spelled the end ...

It was a wonderful idea but it didn't have a chance up here away from fire protection ...

My biggest disappointment is that the house didn't stand long enough to convince the public that it was the ideal way to build a home. [22]"Burritt Says He May Build," Huntsville Times, June 16, 1936, p. 1.

The loss of the house was devastating not only to Dr. Burritt but also to the community. Local businessmen had seen the construction of the house as symbol around which Huntsville hoped to launch its recovery from the impact of the Depression. Shortly after the fire members of the Acme club appointed Tom Dark, chairman of a sub committee, to encourage Dr. Burritt to rebuild. In response to their visit Burritt promised, "If public sentiment in Huntsville is strong enough he will rebuild his home on Roundtop, Monte Sano mountain."[23]Ibid. Before the end of the month Burritt would renew his commitment to build his southern mansion of straw.

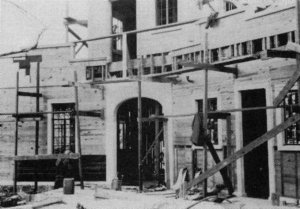

The reconstruction of the mansion began with the raising of a 40 foot water tower of wood. The tower was situated directly above the 50,000 gallon cistern beside the northeast wing of the mansion. Every decision regarding the construction was made to protect the second house against fire. The metal used to line the basement walls was replaced by concrete. The first floor was laid on an eight inch slab which rested upon steel girders. Concrete was also used to construct all the staircases in the house and replaced much of the wood which had ornamented the first house. He even chose cement-fiber-reinforced shingles to replace the original wood clapboard siding. In an interview Dr. Burritt stated that two boxcars of concrete mix were used in the construction of the house and most of the concrete work was poured in place. It would take approximately 40 workers two years to complete the structure. Like the first the house was insulated with bales of wheat straw.

Once completed around the fall of 1938, the house became the centerpiece of a working vegetable truck farm and a goat dairy. Mr. and Mrs. Stone were hired as Dr. Burritt's caretakers and with one mule and the hand labor of their sons they grew approximately 12 acres of crops, including corn, melons, tomatoes, peppers, beans and squash. The produce fed Dr. Burritt and the Stone family. Dr. Burritt sold any remaining produce along Whitesburg Pike.

In addition to the farm produce, Dr. Burritt operated a goat dairy. Twenty to thirty dairy goats, selected out of a herd which was reported to number 10,000, were milked daily by the Stone children. The goat barn was located below the mansion on the western face of the mountain. The goats ranged freely over the mountain sides of Round Top. Efforts were made to confine the hert to Dr. Burritt's property, but long-time residents of Monte Sano and the Blossomwood area recount numerous tales of runaway goats who ravaged neighborhood gardens and landscaping.

The milk from the dairy was stored In the standing spring water accumulated on the floor of one of the abandoned coal mines developed by Johnathan Broad in 1850. The stored milk was bottled by hand and sealed for delivery to local markets and country stores. The farm and dairy operated until the late 1940's, when Dr. Burritt's failing health limited much of the operations.