From The Historic Huntsville Quarterly of Local Architecture & Preservation, Spring, 1994, Volume XX, No. 1.

Historic Preservation has come far in the past 25 years, from building restorations possessing the basic "old timey look" to a down-to-the-last-nail authentic approach of recent years. Perhaps nowhere is this thesis more evident than at Burritt Museum. The museum on Round Top Mountain is a microcosm of the preservation movement during the last quarter century, showing that even on the local level historic restoration work is one of learning, growth, and skill.

In the 1960's the Burritt Memorial Committee began to acquire rural log houses that were to be relocated to the museum grounds and restored to their original appearance. Through generous donations of time, money, and perseverance on behalf of the Committee, three structures were brought to the grounds between 1964-1974. Drawing upon their own knowledge and experience, the members of the Committee hired a local carpenter to complete the work.

of other restorations throughout the country. From the 1960's stand-point, the restorations were satisfactory. They met their intended purpose, giving visitors a "picture" of their rural past and saving the structures themselves from rapid decay and possible demolition. The "preservation" of each structure was accomplished.

During the next 10 years Burritt Museum went through many changes, in both the Board personnel and the hiring of the Museum's first professional staff. A long-range plan was agreed upon for the future, which signaled the beginning of the second restoration phase. Through technological advancements in preservation techniques, as well as the trusty trial-and-error method, the future of a new "historic park" was forged, which after many years of hard work was finally being realized.

In the mid-1980's it was determined that the historic structures once threatened 20 years earlier and relocated to the museum were again being threatened, only by a different enemy. The small trees that were around the structures had grown considerably and were not allowing roofs and walls to dry properly, thereby encouraging rot. Also, after 20 years of visitation, the buildings were showing severe signs of wear, as well as cracked foundations, occasional vandalism, and animal and insect damage. In order to correct all of these worsening problems, it was decided the three main houses would be moved to a more preservation-friendly location. In addition, an interpretive plan was being developed that would give visitors more than a "picture" of past rural culture and would teach much more about 19th century life than just the physical buildings. The three structures relocated were the Balch, Chandler, and Smith-Williams Houses.

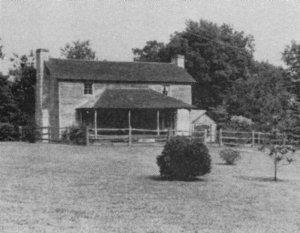

The first to be moved was the Samuel Balch House, originally built in Nebo, Alabama in 1887 and added to in 1898. The area selected for the house was the land behind the Burritt Mansion, comprised of about 12 acres. Once the appropriate land in the Historic Park was selected, in 1985 the Balch House was relocated for the second time. Because of museum reorganization and another project happening simultaneously, the actual restoration did not start until 1989, with completion of the project occurring in 1991. During the four-year span between relocation and restoration, basic research was conducted to bring the house back to how it probably appeared in 1898, after its substantial historical addition. By 1980's standards, the restoration was a vast improvement over its 1960's counterpart, but yet was not perfect.

We must all keep in mind that when dealing with restorations, the end result will never be an exact duplication of how the structure or room appeared at a certain time, as we are limited by materials, money, and documentation. Many of the building materials that were available in the 19th Century are no longer obtainable as new materials. An example of this would be chestnut wood. Because of a North American blight in the 1930's, new chestnut is no longer available as a wood for restoration purposes. This posed a giant problem for us when we had to find replacement logs for our chestnut and oak log barn two years ago. Money is also a driving force as to how thorough a restoration is to be. Luckily for Burritt Museum, we have a restoration staff that has been specially trained for such work. To contract out such work, which we have done and still currently do for simultaneous projects, the cost can be quite high for such specialty needs. The consumer is not only paying for accurate materials but largely hand craftsmanship as well. Finally, documentation plays the ultimate role in determining the accuracy of restoration work.

It would have been fabulous for us if Samuel Balch had taken photographs of every view and angle, both inside and outside his house, for posterity. But it is unreasonable to expect such luxury at a time when photographs were sparingly taken and such photos would have been considered wasteful and eccentric. What we as historians have to do is look at the existing contemporary photographs, as well as other examples of similar structures from common economic backgrounds. Primary documents of all types come into play, such as tax and probate records, abstracts, personal letters, and reminiscences, with the latter constantly being checked for historical accuracy.

Much of the Balch House project was done by trial-and error. We must remember that work such as this was so specialized, it was hard to find trained personnel. What then Director Melinda Herzog did to find craftsmen who could complete such work was to hire two well-versed modern carpenters and send them to training workshops, have them study period examples of existing structures, as well as "learn on the job." It is a fair assumption that each subsequent restoration was better than the one before it, because the skill level involved had improved through "hands-on" activity. Although the finished Balch House was the best possible restoration for 1989, what is currently being undertaken in 1994 is highly regarded by even the most well-known and successful museums in the country.

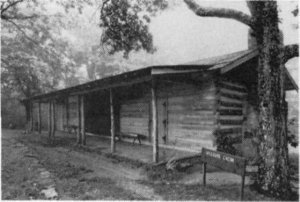

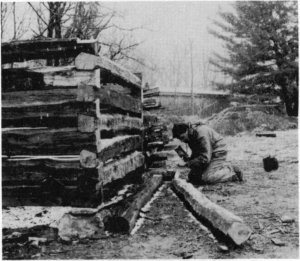

In 1988 a single-pen cabin was offered to the museum from the Leland Gardiner family. It was formerly a tenant house that was built sometime around 1850 and was most likely a slave house originally. It was moved in one-piece to the opposite end of the designated 12 acres of the Historic Park, and the project was immediately begun. The entire interior of the structure was stripped, and an 1850-era interior installed, including a partial sleeping loft. Many of the exterior logs were replaced with contemporary logs of the period, so in essence the project became a restoration/ reconstruction.

It is difficult to determine when a structure crosses the restoration/reconstruction line. Technically, a reconstruction is a new structure that is built of reproduction or authentic materials that when complete represents a former structure that no longer survive. A restoration is an authentic structure that has been taken back to a specific time period, through the use of reproduction or original materials. In the case of the Gardiner Cabin the exterior is about 40 percent replacement, and the interior 100 percent replacement.

It was during this period that the job search went out to find a historian with both a preservation and interpretation background who would oversee the remaining projects (eight total). Once that person was hired, the remaining houses to be relocated from the old Historic Park to the new area were moved. The Smith-Williams was the first, moved in August 1991, with the Chandler House following in November, 1991. A full interpretive plan was developed that outlined what dates the structures were to be restored to, as well as how they were to be used. Once each building was completed, living history interpretation would be implemented in and around the site to tell not only the structure's history, but that of the inhabitants as well.

The park was divided into two areas: 1850 and 1900, and support structures were planned to accompany the houses to add a sense of historical realism. When completed, the historic park would consist of four complete farmsteads that would not only reflect different time periods, but two different economic-levels and lifestyles within each of those periods. In addition to the houses and outbuildings would be authentic field crops and gardens, as well as a variety of woodworking, food and fiber processing, and other relevant indoor and outdoor activities that accurately interpreted rural life.

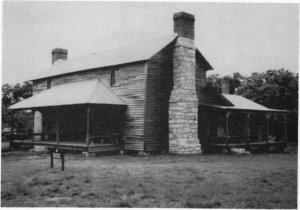

The new Curator's first restoration project was the 1868 Smith-Williams House. Harvie Jones, a highly-recommended historical architect and no stranger to historic preservation, was selected to oversee the project. The Museum's restoration staff installed all the replacement logs and splices, and the finished work was contracted out while the staff started on the next project. The end result was a general depiction of what the house probably looked like in the year 1900. The project was somewhat difficult from the start, as the house had the least amount of documentation of any project attempted. What had to be made was an educated guess on the part of the Architect and Curator as to how the

house looked. Based on his wide range of research photographs, Jones was able to configure what we believe to be a typical subsistence-level dogtrot house. It must be noted that the only original architectural elements left from the 1960's "restoration" were the wall logs themselves. At that time, all doors, windows, roof, joists, jambs, hinges, ceilings, and floors were replaced with modern kiln-dried pine lumber, ceder shingles, and aluminum hinges. This is not to condemn the earlier attempts, but to show how far the field has come since then.

While the Smith-Williams project was progressing, Curator Charles Pautler actively sought a 19th Century barn to better expand the agricultural emphasis of the site. A four crib (or room) log barn was located on property that was for sale near Minor Hill, Tennessee. The owner stated that he could probably receive a better price for the land if the barn were gone, so the barn acquisition was negotiated. The Burritt Museum Guild raised the necessary funding, and the barn was relocated to the Historic Park on May 5, 1992.

The barn, disconnected at the breezeway log, was moved in two large sections, each on a flat-bed truck. The museum staff felt it better to keep as large a section together as possible when relocating a historic structure, as there was less room for accidents to occur, namely pieces disappearing during the move, from whatever reason. No matter how careful a person is to number and photograph a log structure before dismantling, accidents can happen; and there is a strong possibility the building will not go back together exactly as it came apart. That aside, there will always be a certain amount of dismantling that is unavoidable, such as roof rafters, and top and bottom logs that connect major sections. The barn rafters were carefully tagged and photographed, and the plate logs (those running across the top) removed as well. The staff did not have to worry about cutting any sill logs (those across the bottom), as nature had already rotted them in half.

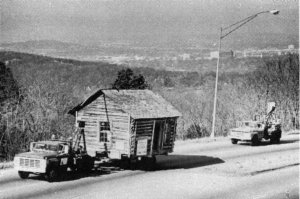

Huntsvillians got to view a strange sight the day of the move, as the 1900 barn rolled down Governor's drive via flat bed trucks. Strangely enough, this was to be a precursor to events that would also happen the following year, but nobody (Museum staff or the public) knew it yet. The barn was placed across from the Smith-Williams House, and would serve as the 1900-era barn for both it and the now-finished Balch House.

Once the Smith-Williams House was completed, the barn was started, which meant a complete replacement of the exterior siding, air louvers, loft flooring, and roof shingles. About 15 percent of the wall logs were replaced with oak logs donated to the museum by Milly Wright of Florence, Alabama, who had worked with the Curator of History on other projects in the past. As with the Smith-Williams House, all sawn lumber for the project was specially milled to the proper historic dimensions and was of the correct wood-type. The restoration was conducted from start to finish by the museum's restoration team that had by now grown from two to five men. One very lucky aspect of the barn project was that the structure had remained relatively unchanged since its initial construction. Original sawn lumber, stall doors, and most of the flooring remained, which meant exact reproductions could be milled to originals' specifications. Original architectural elements that were in good condition were retained for the building, to be reinstalled towards the completion date.

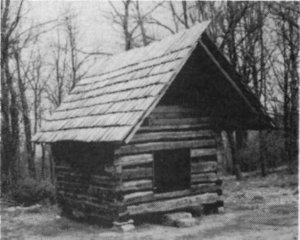

At the same time the barn was undergoing restoration, a corn crib was being reconstructed between the former structure and the house. By this time the living history program was going full swing, and the volunteer labor force was ready to try a project that went beyond fence building and firewood splitting. The Curator of History and the lead volunteer interpreter, Marty Siebert, started the small single room log structure in August, 1992. The building was based on several original examples in the surrounding counties, and constructed entirely of salvaged logs and lumber from various restoration projects. All corner notches were newly made, and the walls were finished about six months later, mainly constructed during the living history program's hours, as well as on assorted weekends. All white oak shingles were hand rived (split) on site, and laid board fashion, with one shingle covering each gap. The structure will be used in 1994 to house the heirloom corn crop that is grown in the park.

The finished corn crib, built by volunteer staff. Note the hand-riven oak roof boards. January, 1994.

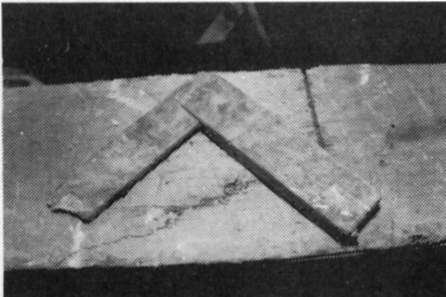

After the completion of the barn and corn crib, full attention was turned to the 1850 site. The only work done thus far had been the restoration of the Gardiner Cabin, the move of the Chandler House, and the installation of split rail fencing. All energies went into the development of the site, with massive amounts of research conducted, and the acquisition of the final Historic Park house. The Chandler House plans were drawn, materials purchased, and the restoration team started on the log replacement. A rear kitchen addition was reconstructed from new poplar logs that were hewn using only the tools and techniques of the 1850 period, such as felling axes, foot adzes, and broad axes. The project should be complete by early 1995.

By the time of the Chandler project, the museum's name was becoming known in the preservation field, and as a result the historical team was asked to consult on several area log

restorations. Partly as a result of these consultations and work done by the Curator on a survey of log structures, Robert Gamble of the Alabama Historical Commission contacted the museum about the possibility of a log house for sale in Limestone County. After talking with Gamble, Charles Pautler decided to make a routine trip to the county for documentary purposes, to do rough drawings and photograph. What he found was a complete 1840-era log saddlebag house. A "saddlebag" is a two-pen (room) log structure with a central shared-chimney. They are generally quite rare in Madison and surrounding counties, and are associated with the earlier settlement period. The structure was entirely covered in clapboard, which preserved the logs from most moisture. Still intact were one room's original windows, doors, flooring, trim boards, staircase, loft, molding, and wall paneling. Although modernized over time, many of the original elements of the house were underneath several layers but nevertheless still present.

For fear that it would not remain for sale very long, the museum had to act quickly on acquiring the house. A special request was made to the Burritt Memorial Committee by the Museum to purchase the house. The Board was in favor, except most funding was tied up in the other restorations. The Historic Huntsville Foundation was approached and graciously donated enough funds to cover half the purchase cost. Without the help of the Foundation, the project could have stalled in this first stage. Once the house was purchased, a research campaign was started to uncover the history of the family that lived within it. After years of working with structures that had limited information associated with them, it was very exciting and refreshing to be working with a house that still possessed most of its original fabric, and had never been previously moved. The staff used all the knowledge derived from years of restoration and documentary experience to start the final and most restoration-significant project to date.

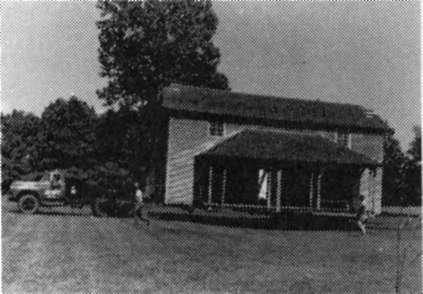

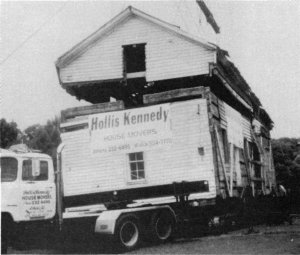

Plans were immediately set to relocate the house, built in 1840 under the direction of James A. Meals, to the Historic Park grounds. Before the house could be moved, all additions had to be cleared from the structure, and a plan devised to safely remove the roof. Because of its one and one-half story height, it was determined that the roof would not clear any telephone, power, or traffic signal lines. After several suggestions by the house mover, it was decided that the roof and top three layers of wall logs would be lifted with a crane and transported separately on another flat-bed truck. The house's length presented a major problem. Because it was 54 feet long, a special set of wheels for the flat-bed truck had to be acquired. Hollis Kennedy who handled the move had all the necessary equipment, and the preparations were made.

The additions that had to be removed from the house included an 1890 front room, a fallen circa 1870 rear bedroom, as well as a 1920's-era rear kitchen and bedroom. The entire process was scrupulously photographed, and most usable lumber was saved for the restoration and other future projects. What was uncovered was a late-federal era log house made from virgin poplar timber, with each room differing somewhat in the workmanship. The interior was left as it was found until the following year.

On July 6, 1993, the James Meals House was driven down Governors Drive, following the same route the barn had taken the year before. Because of the sheer immensity of the house, an old service road through the woods near the Museum's entrance had to be used. It joined the paved driveway near the nature trail parking lot. Tree branches had to be cut along the entire way, as the house was 18 feet wide. The tight curve near the Burritt Mansion was the final obstacle, and the house was reunited with it's roof the following day. The building was set in place, and two days later looked as though it had been there the entire time.

At the same time log replacement was occurring in the Chandler House, the interior of the Meals House was being studied, photographed, and all post -1850 elements removed. Underneath 1960's drywall was 1850's tongue-in-groove poplar paneling. Underneath seven layers of linoleum was heart poplar flooring. 1960's ceiling tile likewise became 1890's poplar ceiling boards, which, after many photographs, yielded to 1840's hewn beams. The structure went through a metamorphosis during the next two weeks, and the history of the occupant's lives unfolded before our very eyes. We decided to remove the paneling so it could be cleaned and reinstalled. The historical artifacts the staff inadvertently found behind the paneled wall were so significant they will be showcased in a special Burritt Museum exhibit. Found were bits of clothing, tools, spools of spun wool, seeds, a corn cob pipe, pieces of weaponry, natural dye agents, hand-forged items, mummified mice and rats, and tobacco paraphernalia, to name just a few objects.

Summer, 1994 the log restoration will begin, to be followed by the house's restored full-length front and back porches, wood shingles, and a mammoth limestone chimney. For a project of this size, Harvie Jones was once again brought in, and at present is preparing the restoration plans. Once the house is finished, the visitor will be able to see the well-trimmed parlor next to the unfinished kitchen. Meals didn't finish the second room's interior until the 1890's. There are still many mysteries, but the existing clues available to us will make this project one of the most thorough restorations the museum has ever undertaken. This is fittingly so, as it shows the preservation community, both local and national, that even a small institution such as ours can provide a large window to the past.

Moving buildings up the mountain to the Burritt Museum and to various locations at the Historic Park has been going on since the 1960's. The movers take extra care to assure the safe arrival of their precious historic cargo.