Llywelyn ap Gruffudd was the last Welsh-born ruler of his country. As the Prince of Wales, he was killed while fighting against the army of England's King Edward I, the brutal "Hammer of the Scots." Llywelyn's severed head was displayed at the Tower of London on a spiked gate as a grisly warning to other potential traitors.

Three decades earlier, the Treaty of Montgomery was signed in 1267 by England's King Henry III. Essentially, it would allow the Welsh people to be ruled by one of their own countrymen. Just five years later, King Edward I set out to conquer Scotland and Wales to establish a unified British continent. His battles against William Wallace, Robert the Bruce, and their fellow Scots in the ensuing years are well known to many, but his annihilation of the Welsh was just as bloody. His thirst for complete domination would earn King Edward I the everlasting hatred of their descendants for centuries to come.

According to one source, Lylwelyn was imprisoned at the Tower of London. Officially, he fell to his death while trying to escape from a high window and his hastily - made rope broke. Unofficially, the rope was tossed out the window after he fell to his death.

When King Edward's son, Edward II, was born at the Welsh castle at Caernarfon in 1300, the king added insult to injury by giving his infant the title, Lord Edward, Prince of Wales. With the exception of Edward II's own son, the tradition of naming the first-born male of the ruling monarch of England, "Prince of Wales," continues to this day.

Among the descendants of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd was Reverend Rowland Jones. Born in Swinbrook Oxfordshire in 1608, he was the vicar of St. James Church at Dorney, Buckinghamshire, England from 1667 - 1685. Today, his name appears on a framed roll inside the small church, which dates back to the 12th century. The historic Dorney Parish Church looks much like it did in Rev. Jones's time.

His son, Rowland Jones, Jr., a vicar at Little Kimble, Buckinghamshire England, came to America in about 1674. He became the first vicar of Bruton Parish, the brick church at Williamsburg, Virginia. Rev. Rowland Jones preached the dedicatory sermon of the new brick church on January 6, 1684, the day of Epiphany. According to Historical Southern Families, the salary of the minister was set at 1,600 pounds of tobacco and cask per year. The cost of interment inside the church was established at 500 pounds of tobacco. For burial in the chancel area, the cost was 1,000 pounds of tobacco. Digging a grave would cost the survivors 10 pounds of tobacco. The baptismal font, imported in 1691, is believed to be the same one that is today placed over the headstone of Rev. Rowland Jones, Jr.

His headstone, in addition to those of his son Orlando and daughter-in-law Martha, are incorporated into the floor in the chancel area of Bruton Parish. The Williamsburg home of Orlando Jones is one of the many interesting restoration projects of recent years.

Orlando Jones's granddaughter became a famous person in America's history - Martha Washington. Another granddaughter would marry Captain John Jones of the 6th Virginia Regiment. He and his son Llewellen Jones (records indicate many variations of the spelling of his name) spent the miserable winter of 1778 at Valley Forge with cousin Martha's husband, George.

On June 13, 1776, Llewellen Jones received a commission signed by John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress. In addition to having fought at Brandywine, Germantown, and Trenton, New Jersey, Captain Jones was with General Washington when they crossed the Delaware.

Llewellen Jones came to north Alabama at about the same time as a group of influential and politically aggressive people from Petersburg, Georgia. Jones was part of the "Georgia Faction," although he apparently had no political aspirations for himself. He purchased 640 acres at the 1809 land sale south of Huntsville's Big Spring and by 1811, he owned over 1,000 acres in the county. In addition, he also owned lots 41 and 42 on Fountain Row and acquired property from a debt owed to him by Irby Jones. He named that plantation Avalon, and today much of the property is occupied by the University of Alabama in Huntsville. He also bought property in and around the community of Greenbrier in Limestone County, known as Druid's Grove. For his daughter, Maria Perkins, he bought land in Lawrence County, appropriately named Seclusion.

Surprisingly, the name Llewellen Jones was common among men of Welsh ancestry. Three men by that name settled in north Alabama, and their records continue to be mistakenly intertwined with each other. In January 1829, one of these men was hanged for murdering his brother-in-law, while another died of natural causes in 1828. But the Llewellen Jones who had been a soldier in the Revolutionary War, would die much more mysteriously.

Llewellen Jones seemed to be on top of the world. His fortune in cotton was increased in 1818 when cotton sold for twenty-five cents per pound. Then in 1819, cotton prices spiraled downward and the extreme financial straits that first hit the cotton farmer rippled to everyone who depended on cotton in one way or another. The financial panic of 1819 hit Jones hard, and nearing the age of 60, he felt he could not cope.

In a letter dated January 27, 1820 to Senator John Williams Walker, also a member of the Georgia Faction, a friend wrote, "Llewellen Jones put a period to his existence last night by hanging himself,..."

On Saturday, January 29, 1820, the Alabama Republican ran the following story:

"Suicide - On Wednesday the 26th instant Mr. Levelling Jones, resident in the vicinity of this place, put an end to his existence, by hanging himself with his pocket handkerchief. Mr. Jones was a man in affluent circumstances, and had just moved to a beautiful country seat near Huntsville, which he had recently purchased. No probable cause has been assigned, for his committing this violence on himself." According to local gossip, he hanged himself from a joist in the home that was still under construction.

Jones's survivors would weather the cotton crisis, as did countless others who were affected even more seriously. Llewellen's son Alexander inherited Avalon, and his other son, John Nelson Spotswood Jones, who was an attorney in Huntsville, lived at Druid's Grove with his large family. His law office doubled as the first public library in the state of Alabama.

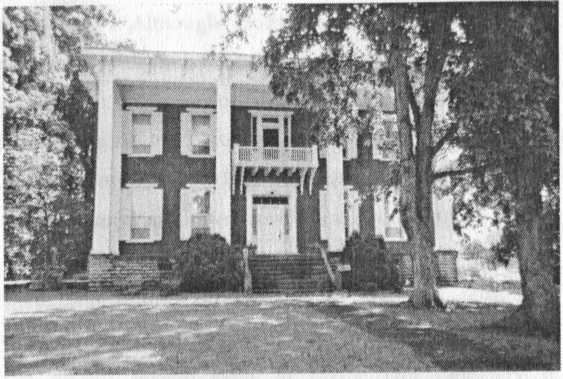

Family records for the next forty-five years indicate prosperity and prominence for the Jones descendants. The Civil War brought another kind of crisis that would financially destroy them. Their homes and fortunes were decimated. John Nelson Spotswood Jones and his wife were already deceased before the war, along with several of their children. Their son, John Haywood Jones, had just completed his beautiful home on Clinton Street in Athens, Alabama when Col. Turchin and his men came to call during the infamous Sack of Athens. The devastation of his home and his life were apparently too much for him to bear. According to a family story, John went to Chattanooga where he checked into an inn and drank himself into a coma that resulted in his death. His 10-year-old son died 5 days later. Their graves are in the Jones-Donnell cemetery in a Greenbrier cotton field. Headstones there mirror the ebb and flow of family fortune. Before the war, elaborate works of art grace the graves of those privileged people who lived at Druid's Grove, while just a few short years later, sunken earth is all that remains of the now-anonymous people who died prematurely.

Today, there are still unanswered questions. Alexander Jones, who inherited Avalon, never married, but had children by a slave. He was described as a "peculiar old botchler." It was said that he would buy old horses, knowing they would be of no use to him on his plantation. To his credit, he treated them humanely until their deaths.

Alexander's descendants continued to live at Avalon until the land was appropriated for the college campus in Huntsville. They remain proud of their heritage and have become scholars of the Jones family and its contribution to North Alabama.

After his suicide, Llewellen Jones was buried in an unmarked grave in a Jones family cemetery that is behind present-day Morton Hall on the UAH campus. In the 1970s, the Twickenham Town Chapter, Daughters of the American Revolution, marked his grave in a beautiful public ceremony. While many of the Jones descendants wondered why such a wealthy man's grave was left unmarked for so long, it only recently became clear that the details of his death were carefully excised from the family records. Perhaps his immediate family felt the stigma of his suicide and chose not to erect a marker.

For whatever reason he chose to hang himself, there is evidence that some anonymous person does not condemn his action. Visitors who occasionally wander to the small cemetery surrounded by a wrought-iron fence, find that he is appropriately honored for his contribution to American freedom. Each year around Memorial Day, a small American flag is placed on the grave of patriot Llewellen Jones.