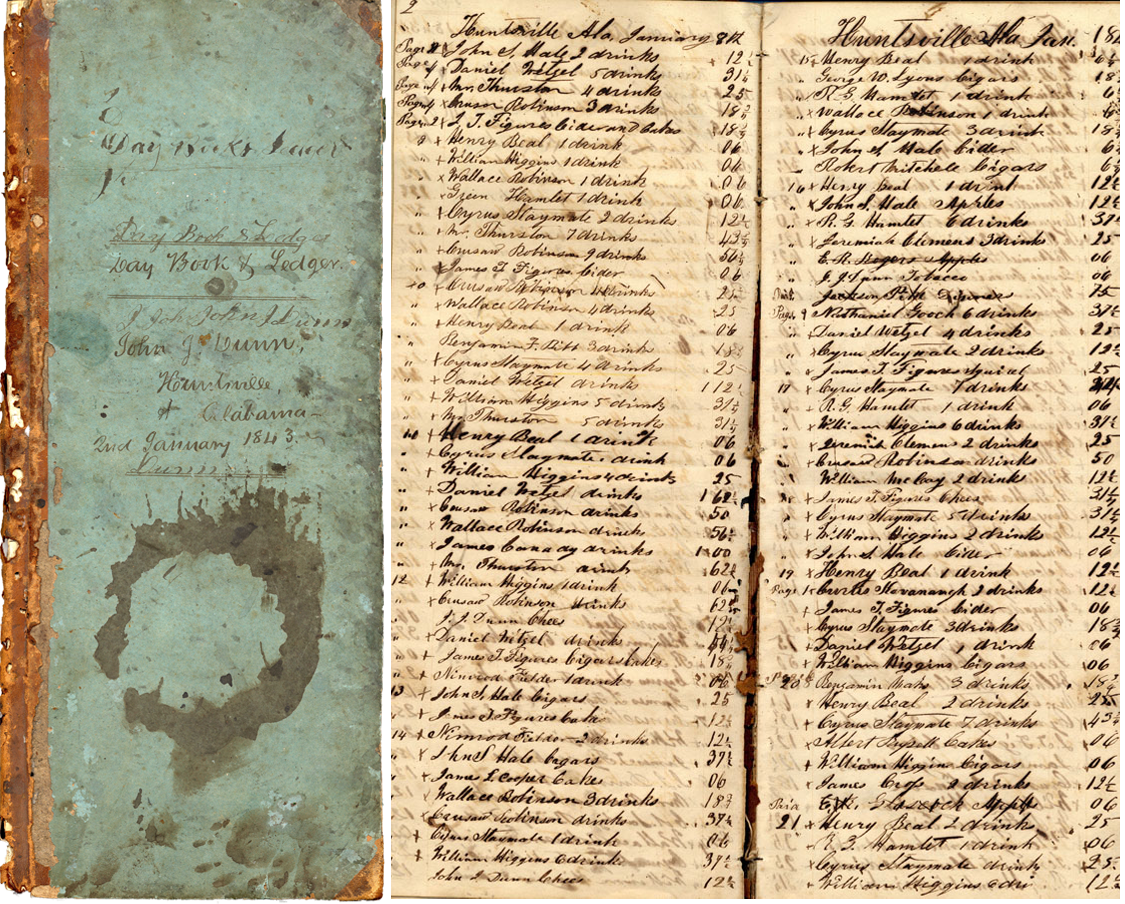

This single unpretentious, uncompleted account book was kept by one John_J._Dunn in Huntsville, Alabama, for the first half of the year 1843. The cover says so. Several times. And that is about all one will learn about John J. Dunn.

The year 1843 was not particularly memorable in Huntsville history, but then neither is Dunn's Tavern ledger. (The ledger's value was apparently not recognized, given that children later practiced arithmetic and pressed leaves throughout the empty pages.)

Although the ledger records entries made during a brief six-month period, it offers a glimpse into the lives of a small section of citizens—actually about 140 men. Indians, slaves, and women, of course, did not appear in the account book. It was against the law to serve or give alcohol to Indians or slaves. By 1843 most of the Indians had been removed from Alabama, and this was hardly an issue. However, it was well known and county officials periodically reminded all tavern owners and liquor sellers that they would be guilty of keeping a disorderly house if they sold "spirituous liquors" to any slave who did not have written permission from his master. Furthermore, a tavern keeper found guilty would not be able to obtain a permit to sell in that county again.[2]"A Warning to Tavern Owners," Old Lawrence Reminiscences, vol. 17, #4 (Dec. 2003), 15, 22. The liquor business was robust in that northern Alabama County. In two years (1852-54), 28 licenses were issued by the county officials. Of these, one license was to sell the slave Johnny; one was to keep a 10 Pin Alley; two were to keep a billiard table; three were for peddling with a wagon; seven were for keeping a tavern, and fourteen licenses were to retail spirits.

If a female appeared inside Mr. Dunn's tavern, she was there as a menial worker. This is not to say there were no arrangements in town for women. At the nearby Huntsville Inn as early as 1823, ladies were welcome and could be "perfectly retired" and accommodated with ice cream, cordial, cake, soda water, etc., at any time of day during the summer. Gentlemen might enjoy the fine, cool, well-furnished Reading Room where they would be offered cold cuts, hot coffee or tea and any kind of drink that they might want; a choice of liquors was also available.[3]Sarah Huff Fisk Historical Collection, 1823 notes Huntsville-Madison County Public Library Heritage Room. (Hereafter cited as Fisk Notes.)

----By 1843 Huntsville, the county seat of Madison County, consisted of about 2000 people—black and white. (The population grew to only 2863 by 1850.) As one might imagine, Huntsville offered its visitors and citizens many of the finer things.

County leaders selected local architect George Steele to plan and build a new jail in February 1843. They levied a tax for the new building to replace the old, "deplorable" one. Some of the men at Dunn's Tavern just might have been familiar with the old facilities, even if it were only to visit an acquaintance. The handsome bank designed by Steele was already eight years old. Adding to the thriving prospects for business, the fine new Court House, also designed by Steele, was finished the year before. The Market House had recently been completed, conveniently located in the center of town, resplendent with stone steps and a stuccoed front with pillars.[4]James Record, A Dream Come True, Vol. 1 (Huntsville: Hicklin Printing, 1970), 95.

In order to do business in a growing town, transportation was essential, and it was commonly accessible here. Dr. Fearn's Indian River Canal, perhaps then at its peak, allowed keelboats carrying 80-100 pound bales of cotton and passengers from the Big Spring to join the Tennessee River at the bustling town of Triana. If the River was flush, goods could go on down past the Shoals and then eventually to New Orleans. Although the Tuscumbia, Courtland & Decatur Rail Road was being built as fast as money allowed, it had not reached Huntsville yet. As a result roadways were still particularly important. Much of the state was undeveloped, but Madison County maintained 50 miles of first-class and 80 miles of second- and third-class roads.[5]Ibid. These thoroughfares allowed travel in and out of town for business at the courthouse, to sell or buy cotton and other produce, to visit with friends or relatives, and perhaps to linger at a favorite tavern before retiring overnight at an inn or returning home. Local customers could conveniently drop in more often. Some did.

----

Alcoholic spirits were certainly not uncommon on the frontier. A local house-raising or corn-husking often ended with a jug or bottle commonly shared, even if it was out of sight behind the barn. Weddings might be celebrated with a toast of wine or something stronger. Summer barbecues, political ones particularly, encouraged citizens to gather and socialize. Horse racing and card playing, typically male bastions, certainly included alcohol. Voting day also brought the men together at election sites. Militia muster days required all free men between the ages of 18 and 45 to attend. The day became a social gathering that allowed the children to play, the women to make a few pennies selling gingerbread, and the men who trained hard to cool off with a beverage of their choice. At these occasions, unlike other aspects of frontier life, differing levels of the social order mixed freely.

If the pioneer family found a need to justify the presence of a bottle of whiskey at the home place, the use of distilled corn liquor was known for its many medicinal properties. Most doctors were located in urban areas, so farm families likely had whiskey on hand or knew from which neighbor to borrow some. Alcohol was commonly used to treat just about every ailment. Mixed with other available ingredients it could become a liniment that was good for sore muscles and aches and as an antiseptic for wounds. Taken internally, perhaps mixed with sugar, honey or spices to make it more palatable, whiskey treated "coughs, colds, croup, whooping cough, sore throat, colic, dysentery, consumption, pneumonia, asthma and arthritis." And don't forget "colic, pneumonia, rheumatism, hookworm, catarrh, snakebite, 'yaller janders' (jaundice), gall bladder, frost bite, snakebite, broken bones or breaking a fever."[6]Nicholas P. Hardeman, Shucks, Shocks, and Hominy Blocks: Corn as a Way of Life in Pioneer America (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State Univ. Press, 1981), 177.

Many homes served wine and whiskey for their own personal enjoyment. Middle class and professional families, unless their particular religious beliefs interfered, had the availability of spirits purchased in town. Although in case there was any doubt, one might easily cite the biblical source, Timothy 1:23, "Drink a little wine for the stomach sake." Or as the Puritan preacher Increase Mather wrote, "Drink is in itself a creature of God, and to be received with thankfulness." Well-to-do plantation owners, whether at their country home or their town house, took pride in their fine display of sets of glassware and silver and offering a libation to their friends or business associates.

One traveler noted that whiskey was the south's favorite beverage. However, Judge Taylor wrote:

The people were generally sober in their habits, yet temperance was not considered a cardinal virtue. Among the wealthy of the community it was universal custom for the old fashioned side boards to be well garnished with a good assortment of decanters consisting of fine liquors. Pure corn whiskey was a universal beverage and our ancestors partook of it freely, yet while the majority of them drank it every day but few of them were drunkards.[7]Grady McWhiney, Cracker Culture'', (Tuscaloosa: Ala.: Univ. of Alabama Press, 1988), 90. Judge Thomas Jones Taylor, ''History of Madison County, WPA version, 1940, 83, 84.

It may be surprising that cotton, the most well known Southern crop, was in fact planted second by frontier families. Corn, such an essential staple, was universally planted first. Corn raised around newly hewn tree stumps provided food for farm animals and farm families alike within one growing season. Farmers, who found themselves with a surplus of corn not needed for home use, recognized the bulk and inconvenience of carrying an excess crop to market. A horse was not even able to carry enough corn to feed itself if town was far away. As a consequence whiskey production provided an ideal solution. A farmer could reduce two clumsy five bushels of corn to a five-gallon batch of whiskey - much easier to enjoy, store, transport, or turn a profit and sell. A mule might carry about four bushels of corn, but distilled into whiskey a mule could haul the equivalent of 24 bushels of corn. A horse could easily carry two kegs, about 24 gallons total, of liquid. Cash was a scarce commodity on the frontier, and was always welcome. One bushel of corn worth fifty cents became worth one to two dollars a gallon.[8]Donald Edward Davis, Where There Are Mountains'', (Athens, Georgia: Univ. Georgia Press, 2003), 140; Hardeman, ''Shucks'', 234; Bruce E. Stewart, "This Country Improves in Cultivation, Wickedness, Mills, and Stills," ''North Carolina Historical Review'', Vol. 53, #4 (Oct. 2006), 461; Everett Dick, ''Dixie Frontier: A Social History (Norman, Okla: Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 1993), 254.

In north Alabama most of the settlers' background was one or two generations removed was of the Scots-Irish tradition. The men were often already quite knowledgeable about whiskey-making and many Madison County probate estate packets attest to the presence of copper tubing and other supplies for stills.

In the village of Huntsville, one could also purchase manufactured spirits from the local stores. For instance Mr. Rapier the Grocer boasted newly arrived products that included among other goods two kinds of sugar, tea and coffee, wines, rum, and gin. AT his tavern, John Biddle offered first quality Pittsburg Porter by the single bottle or by the dozen. Neal & Fariss Druggists offered the best Port Wine, expressly for medical purposes. They also just happened to have "in stock one cask of real Old Pale Cognac Brandy as good an article as was ever brought to this market."[9]Sarah Huff Fisk, Civilization Comes to the Big Spring: Huntsville, Alabama 1823''. (Huntsville: Pinhook Publishing, 1997), 60; Fisk Notes; Huntsville ''Democrat, May 11, 1843.

----Although alcohol clearly was available in many homes and for purchase in stores, the tavern truly filled a need. Here one could gather after the long day's work and socialize with those who had similar attributes and concerns. One could meet other like-minded men, or contrary-minded men, to discuss religion, politics, a bit of gossip, crops, news of the day, or even the weather. Furthermore, locals knew they could arrive later and continue the conversation from their last visit. An appointment in town for men on business sometimes might allow a stop for incidental sociability and solacing liquors before the long trip home. However, taverns really served to comfort townspeople, and for the interchange of news and opinions. The tavern was a highly controlled place but a widely accepted gathering spot.

Indicative of the very earliest regulations, by 1818, a bond of $300 was required to keep a tavern. This bond was issued by the Governor of the Alabama Territory. The license could be renewed if the keeper provided "his tavern with good clean wholesome diet, lodging for travelers, and stabling provender and pasture for horses." In nearby Lawrence County, Alabama, the 1838 tavern rates were posted for boarding, meals, and boarding for animals. The rates in Madison County would have been similar. Among items available:

| Whiskey half pint | .12 ½ cents[10]Old Lawrence Reminiscences, vol. 16, #2, p.42, 43. Included in the tax rates, every Bowie knife or Arkansas Tooth Pick sold, given away, or otherwise disposed of was taxed at $100. |

| Whiskey per pint | .18 ¾ |

| Peach & Apple Brandy, half pint | .18 ¾ |

| Peach & Apple Brandy, per pint | .31 ¼ |

| Peach & Apple Brandy per quart | .50 |

| French Brandy, Rum, Wine, Imported Gin per half pint | .25 |

| Single Drink Whiskey | .06 ¼ |

| Cigars (Spanish) dozen | .37 ½ |

| Cigars (Common) dozen | .12 ½ |

Judge Taylor noted the strict regulations that included rates:

| 1 quart Wine | 1.00 |

| ½ pint Jamaica Rum | .50 |

| ½ pint French Brandy | .50 |

| ½ pint Whiskey[11]Taylor, History, 96. | .12 ½ |

Many early settlers of Madison County came by way of Grainger County, Tennessee. John Hunt, founder of Huntsville, had been a prominent citizen there. Among the men who also settled here, Hunt already knew Clement C. Clay, later to become the 8th governor of Alabama. Clay's sister, Margaret, had married a neighbor, John Bunch, in Grainger County. In 1796 Bunch established a tavern near Rutledge on the main road from Kingsport to Knoxville in a building, which also served as the first Grainger County courthouse. It did not hurt business that John's brother, Samuel, was a captain in the militia and sheriff of the county. On court days, commissioners enacted laws regarding county business. Because they were already in the courthouse/tavern, it made a fine gathering place to conduct business and consider a bit of politicking.[12]LaReine Warden Clayton, Stories of Early Inns and Taverns of the Tennessee Country. (Nashville: Knoxville Committee of National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the State of Tennessee, 1995), 102.

Bunch's double-walled tavern in Tennessee was built to resist Indian attacks. There would be no need for that at his next location, called Bunch's Tavern, in Huntsville, Alabama. Once established, the tavern on the south side of the Square also served as courtroom for the newly formed Madison County at the January session of the Superior Court in 1810. The long white frame building was one of the few places on the Square large enough to hold the crowd. On court day, Sheriff Stephen Neal began the formal procedure as he came into the room and advanced to the bench with drawn sword. Next, "Judge Obadiah Jones entered the courtroom with great ceremony, clad in a Judge's gown, a cocked hat, with long plumes and a sword at his side." Sheriff Neal claimed reimbursement for $3.70. His arrangements included three home-made chairs with buckskin bottoms, table, paper, and goose quills for this courtroom at the tavern.[13]Judge Thomas Jones Taylor, History of Madison County and Incidentally of North Alabama 1732-1840. eds. W. S. and Addie S. Hoole, 120.

Clement Clay, just newly graduated from law school, visited his sister here in the spring of 1810. Clay liked what he saw and returned to establish his law practice the next autumn, joining his former neighbors including Hunt, David Tate, Major Lea, Phelps Read and others from Grainger County.[14]S. Emmett Lucas, Goodspeed. 1887 Rpt. 1991, History of Tennessee. (Ensley, SC: Southern Historical Press.), 853, 854. Original 1887. Naturally, they would gather at a known respectable place - Bunch's Tavern.

Madison County was growing, and as the area continued to develop, Alabama Territory prepared for statehood in 1819. Influential men arrived to write the new constitution. After the work of the day was completed, it was expected that the men would gather at local inns and taprooms to discuss the events and plan their own particular political strategies. The tavern was an accepted public space for democratic elbow-rubbing. Likewise, the need for locations of rest and hospitality also continued to grow. Locally, perhaps the most famous hostel was Green Bottom Inn and Tavern, owned by John Connally. General Jackson, always an astute politician, appeared in town and stayed at Connally's during the preparations for statehood. Jackson was an avid horse racing fan, and when the Madison Jockey Club held seasonal races the prize money was often as much as $1000 with several races in one day.[15]2009 equivalent value nearly $18,000. And that did not include individual bets made on the side!

----The stagecoach routes traveled from Huntsville to Tuscaloosa by way of Somerville, to Tuscaloosa by way of Blountsville, to Florence, and another to Tuscumbia. Travel by stagecoach or horseback was slow and limited to about 20 miles - on a good day. Numerous inns and taverns for stopping along the way for bed and board were necessary in any county. Bed often meant three or more to one bed, and board for the horse was more costly than meals offered to the traveler. It wouldn't have mattered if the bill of fare for travelers was labeled breakfast, dinner or supper. The food served was likely to be some variation of pork and corn bread, often washed down with whiskey. Traditionally, taverns were open on Sunday with the understanding that no host would "on the Sabbath Day suffer any Person to Tipple or drink more than necessary."[16]Harriette Simpson Arnow, Flowering of the Cumberland, (Lincoln, Neb: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1963), 24.

There were many tavern locations in Madison County. For instance, Joab Watson maintained an inn furnished with an extra large library, some of the best papers of the U.S. and an assortment of large maps. Fees, of course, were standard for meals, lodging, and stables. All this was conveniently available just three miles west of Huntsville at the well-located site of Mount Pleasant, on the roads to Triana, Mooresville, Cottonport, Athens, Florence, Upper and Lower Elkton, and Pulaski. The Planters' Hotel at Triana wished "to rent this valuable establishment; it is well fitted up, new, convenient, and desirable as a stand, has an excellent Ball Room, and a superb Stable, with every necessary out house." In Mount Airy, four miles north of Huntsville on the Pulaski Road, Samuel Vest offered satisfaction by his table and stables, good and wholesome food and drink for man and horse. Not to be outdone, a tavern, the "best the country could afford in table and bar," was opened at Hazel Green.[17]Fisk Notes.

Perhaps regulations were not always as closely watched in the county. At New Market ten licensed saloonkeepers offered "whiskey made in the neighborhood sold for 25 cents per gallon." The customers generally knew "to remove their shot pouches with their accompaniments, usually a large knife, powder horn and powder-measure, and put them over their rifles in one corner" while they socialized. However, alcohol became such a problem later that the State Legislature passed an act forbidding the sale of whiskey within a three-mile radius of that settlement.

"This was done in order to enable the inhabitants to live in peace and quiet. Nights were made hideous and the days, particularly Saturdays, were scenes of blood-spilling, fights…pistol shots, frightening the very souls of our adversaries. The hands of the surgeon were bloody all day dressing wounds. One person during an exciting election drove down the neck of a decanter containing whiskey and nearly cut off his hand near the wrist."[18]Memories and History of New Market, Alabama'' (New Market Volunteer Fire Department, n. p., n. d.,) 3; Dr. George Norris and Dr. Francisco Rice, ''History of New Market'' comp. by Estelle Brahan from ''New Market Enterprise, 1888.----

In Huntsville, bustling with activity, the need for lodging continued to rise. At Bell Tavern, management announced they had added 20 rooms, making a total of 66 rooms available for the weary traveler. Landlord James McLaran respectfully informed the public that he was open for business at a "valuable tavern stand... where he hopes by his unremitted attention, and endeavours to accommodate all who may favour him with their custom, to give universal satisfaction. His bar will at all times be furnished with an assortment of choice liquors, etc."[19]Record, A Dream, 89; Fisk notes.

----Because a tavern often had a larger floor space than most other buildings, amusement and entertainments were performed there for the enjoyment of visitors and the local community. For example, in March of 1822, members of the Sons of Erin met at the Globe Tavern (formerly Bunch's Tavern) to celebrate the anniversary of their favorite saint. At five o'clock they and their guests sat down to an excellent dinner and toasts were drunk.[20]Fisk Notes.

Scotsman Neil Rose ran a tavern under the sign at the Planters' Hotel. His overnight guests were assured there would never be more than four to a bed. One of the guests, Anne Royall, wrote that after finishing a game of backgammon, the men stirred up the fire and discussed the philosophy of the day. They likely also played drafts, checkers, and dominoes. Allen Cooper offered more sophistication at his nearby establishment. He advertised his House of Entertainment with the best accommodations. "There is a hydrant in the bar room, and but a few turns of the tap furnishes water as cool as if dipped out of the spring in addition to that plenty of ICE."[21]Fisk Notes; Anne Newport Royall, Letters from Alabama, 1817-1822. (University, Ala: University of Alabama Press, 1969), 121; Fisk Notes.

In its prime, the Bell Tavern offered entertainment by a travelling theatre group who performed the play "The Robbers" that even included extra scenery! At that tavern many people in Huntsville saw and heard their first, and perhaps only, ventriloquist. A lecture on Philosophical Chemistry with beautiful experiments included a juggler who gave the appearance of vomiting fire was another attraction. In 1837 Warren, Raymond & Co. Menagerie, Circus and Museum offered the public "the largest collection of animals ever exhibited carried by 30 carriages and pulled by 100 matched gray horses."[22]Fisk Notes; Record, "Dream", 91; Fisk Notes. One hopes the animals remained outside.

----All taverns licensed to sell spirits were carefully regulated. Owners almost certainly were regarded as respectable men who would conduct a respectable business and provide a needed service. Just who were the men sanctioned to run a public tavern in early Huntsville? Nine men, including John Dunn, had been given licenses to sell spirits in 1830. Among them one man, Vincent Small, was noted in the 1830 census in the 20 to 30 age group; William G. Stringer as 30-40; and two men, Rider S. Floyd and Elijah W. Warren between 40-50 years of age. Dunn, P. G. Oliver, James Lang, Spencer Sydney, and John Finlay were not listed in the census of the county that year. Reflecting the mobility of the frontier, by 1840 only two of those men, Warren and Dunn, remained in the county. Not long afterwards Elijah Warren moved to Lauderdale County, and at his death in 1844 he was noted as an old citizen.[23]Huntsville City Council Minutes., Roll #1, 1828-1869, Feb. 1830, p. 121; May 17, 1831, p. 127; Dec. 6, 1830, p. 132; and Dec. 23, 1830, p. 134; 1840 Federal Census; Pauline Jones Gandrud, comp. Marriage, Death and Legal Notices from Early Alabama Newspapers, 1819-1891, (Easley, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1982), 481.

There is no information at this time to positively identify John J. Dunn, keeper of this particular daybook and ledger. He was not located definitely in the Federal Censuses for 1830, 1840, or 1850. Probate, church, cemetery, local history books, and newspaper articles do not name him specifically during those years in Huntsville. There were men listed as John Dunn, John H. Dunn and John K. Dunn. These could be one and the same perhaps, depending on the accuracy of the scribe. There is no doubt that one Captain Dunn was given license to operate a tavern.

It is likely that John Dunn was the man who served as a First Lieutenant when the Huntsville Light Infantry Blues were organized in 1822. As a solid and respected citizen, John Dunn probably was the same man who led many of the festivities for the Fourth of July in 1824. The celebration "was ushered in by firing from the Volunteer Company commanded by Captain Dunn. After the usual evolutions, a procession was formed by the military and citizens, who marched to the Presbyterian Church where after an appropriate prayer… and the Declaration of Independence was read."[24]Edward C. Betts, Early History of Huntsville, Alabama. (Birmingham: Southern Univ. Press, rpt. 1966), 89; Fisk Notes.

The county marriage records do show one John [NMI] Dunn married Rebecca Renno in 1828, an appropriate time frame. If Mr. Dunn had a family with him, most likely they lived in the back of the tavern or in rooms upstairs. The tavern itself would be dark, lighted only by candles at night and with the fireplace to add warmth when needed. One does not necessarily need to see well to enjoy drinking or good company. The men sat on three-legged stools, perhaps at a table, or stood near the fireplace in the winter. As was the custom for the times, they chewed and spat tobacco, smoked cigars and it was just as well women didn't frequent the establishments.

Probably many customers came in off the streets to order a drink and paid cash at Dunn's Tavern. This combined daybook and ledger apparently recorded only the "tabs" of various citizens to whom Dunn extended credit each day the tavern was open. The daybook section listed the names and the orders, and the ledger section totaled the amount of money each customer owed, and if it were paid. (Many tavern keepers recorded a daily tab on a chalkboard, which was recorded into a ledger, and the board was erased each night.) Dunn probably served many other customers for cash at the sale.

Dinner or supper was available for 37½ cents, but that was recorded fewer than ten times. About ten different men came in to purchase sundry goods like tobacco, cigars, cheese, pickles, apples, coffee, and cakes and perhaps have an excuse to talk over the events of the day. The largest volume of credit was extended for a single drink at the price of 6¼ cents (about a ¼ pint of whiskey) unless it was for two, or three, or even more drinks.[25]2009 equivalent value approximately $1.75. Surely when Dan Wetzel ran a tab on January 11th for $1.62½ he was not drinking alone but buying a round for his buddies. Perhaps he lost a bet, celebrated getting paid, a new job, or just because he felt good. It must have been a merry party that evening because several men charged amounts indicating several drinks each.

The largest total tab for the six months went to William Higgins for $15.37½, followed by Crusaw Robinson, George Carmichael, and Cyrus Staymate all well into $14 worth of credit. One can only guess at the actual cash sales that might have been made and not recorded in the daybook for various reasons. Most accounts in the ledger ranged from less than a dollar to a bit over three dollars.

Local folks might later recall some of the events of that winter of 1843 while men frequented the tavern.

In January the heaviest snowfall in ten years occurred, over eight inches in all.[26]Record, Dreams'', 97. Farmers worked at indoor tasks as much as they could, and travelers waited until the road became passable. City folks frequented their neighborhood establishments. Mary Lewis reported to her daughter in Paris that all over the county citizens were alarmed as an earthquake struck on January fifth, and chimneys were toppled in faraway Memphis and Nashville. According to Ma Lewis, only emotions were shaken locally.[27]Nancy M. Rohr, ed., ''An Alabama Schoolgirl in Paris, (Boaz, AL: SilverThreads Publ., 2001 ), 94.

Even though the men might not have discussed it, the ladies of town would have been all agog because that most eligible bachelor, Clement Clay, Jr., had just married in Tuscaloosa. He and Virginia Tunstall were wed on February 1st in what must have been a dazzling ceremony in the new frontier capitol town, Tuscaloosa. The Legislature adjourned early so members could attend the ceremony. In Huntsville, the men at Dunn's tavern would have heard the young couple's arrival on February 17th into Huntsville. The stagecoach approached the public square, and the horn was blown as they passed before heading down Clinton Street to the family home, Clay Castle, aglow with candles and bursting with relatives to greet their new sister.[28]Ruth Ketring Nuermberger, Clays of Alabama, (Lexington: Univ. of Kentucky, 1958), 83, 84.

Surely the men discussed and cussed at the news in early February of the liquidation of the Huntsville branch of the State Bank of Alabama.[29]Record, Dreams, 95. Perhaps men of modest means raised a glass because they had little invested in the bank; well heeled investors raised a glass to drown their sorrows.

The regulars at Dunn's watched as the old jail was torn down and sold for scrap in March in preparation for the new building. Construction also began as Thomas Brandon started work on the city reservoir.[30]Ibid.

Everyone in town heard about the street fight between Clement Clay, Jr., and Judge John Thompson in late March. Clay displayed great anger, striking Thompson about the head and nearly cutting off one ear. There had been no need to fight according to Ma Lewis; it was all about words. She also suggested young Clay had more difficulties than mere words facing him.[31]Rohr, School Girl, 109, 110, 119.

The Huntsville Temperance Society held their first meeting at the Methodist Church in March to form a chapter. On April 16th at the Society meeting there was a beautiful lecture. Nonetheless Judge Thompson, who apparently had recovered from his wounds, or was still suffering from them, scourged the Methodists. "He accused the members of their own church of drinking." Angry words followed from Mr. McDowell in reply. There was a "great shaking of dry bones amongst them, and I understood they would form a committee...." Judge T. said, "My friends I fear temperance is at low ebb here. It is even prophesied by the malicious, that, as there is a great quantity of ice put up and that the mint crops are so fine, that here will be a great falling off in the cause this summer." Great laughter from the audience followed.[32]Ibid., pp. 132, 133 Of course, all those attending were urged to sign the pledge of abstinence. Several temperance groups were formed that spring, and some of the fellows around the bar at Dunn's Tavern may have missed those meetings. Perhaps their wives attended.

By mid-April another brawl was noted on the Square. Accusations were tossed about, and Joe Acklen and Mr. Gardiner from Mobile engaged in a fistfight. Gardiner's eyes were blacked, but the family honor was salvaged.[33]Ibid., pp. 40, 141.

Rumors had been flying about the disgraced Boardman brothers, Elijah and John. All the men would have paid particular attention to these events. Elijah ran a nationally recognized breeding and stud farm for racehorses in the western part of the county. Although John had held public office and ran a local newspaper, he was indebted to the America Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb for $37,000. He had sold land that the Asylum owned in Madison and Limestone Counties and was unable to reimburse them. Elijah and other relatives covered the debt, and after John returned from Paris where he had gone "for his health," the brothers decided to sell out everything here. In April they moved to start anew in Holly Springs, Mississippi.[34]ref>See Nancy M. Rohr, "Off to the Races," Huntsville Historical Review vol. 35, #1 (Winter-Spring 2010), 35-57. Rumor likely followed them all the way.

A crowd of people came to hear the Brass Band perform an elegant concert at the Big Spring as the weather continued to improve. The music included hymns, marches and the Marseilles March to raise $100 for charity. The highlight of the evening was the newly composed "Huntsville March" written by Mr. Catherens the band leader.[35]Rohr, School Girl, 117.

----To identify all the customers in the tavern account would be impossible. A very few names were totally illegible. Obviously many of the men were from out of town, probably doing business. They might have stopped in with a friend or just to join a genial group for a little comfort and spirits before retiring for the night or returning home. However, studying their surnames offers some possibilities. Each of the men had a story to tell, if the reader only knew.

Names, most often written as "Mr.," implied that tavern keeper Dunn did not know their first name. They appear to have been travelling men because they generally could not be located in most Madison County documents. Nevertheless, the Federal Census of 1850 offered some clues. A John Chandler lived in Benton [Calhoun] County. Likewise, Henry Hite Hiram Duncan was enumerated in Pickens County. Mr. Cushing was likely a visiting merchant; there was a George Cushing in Baldwin County. Mr. B. F. Dibbs well could have been Bennet Dibbs of Cherokee County, Georgia. James Hood was a farmer in Pickens County. Mr. Edwards from Mobile also was probably here on business. The two serious-drinking Robinson men, Crusaw and Wallace, and Thad Robinson remained unidentified, but most likely they were related to one of the prominent Robinson families of Madison County. The name Bettersworth was unknown here but very common in sections of Kentucky. Mr. Larry possibly was John Larry, age 56 in 1850, a farmer in Tallapoosa County. Although Lyons was a common name in this county, none were named George. Perhaps he was George Lynes, an Athens coach maker, age 57 in 1850. One might think names like Daniel Wetzel and Jackson Pike, written so clearly, would easily be identified, but not so.[36]U. S. Bureau of the Census, Seventh Census of the United States, 1850, Madison County, Alabama. Because of the unavailability of information and difficulty in reading the script, at least forty men remain unidentified.

Searching for identity one might find John Brown, "an old and respected citizen of this county died in March 1880 of cerebral abscess of brain. He was a brother of Capt. James H. Brown of this city." The name J. Bailey was a thorny entry because there were at least two local possibilities. Joseph F. Bailey (1816-1867), veteran of the Civil War and "an old and well known citizen," died here. Also a James Bailey lived in the western part of the county. James W. Canady in July of 1840 served as secretary at a Democratic meeting at Larkinsville in Jackson County where he operated a mercantile business. It was reported in the local newspaper that Private Robert Capshaw of Company F, 3rd Regiment of the U. S. Army was being attended at the 3rd Dragoon Hospital, Matamoros, Mexico, in July 1847.[37]Gandrud, Marriage, 221, 570, 488, 335, 491. It is most likely young Robert was related to any number of folks from the Capshaw community here.

Marriage records offered information about William M. Barton who, in 1837, married Elizabeth Debow. James L. Browning married Catharine A. Smith of Huntsville that year. Although Bell is a common name in Madison County, there was only one notation for William P. Bell who, in August of 1843, married Lucy Frances Couster in Huntsville. William Hendricks married Mrs. Mary Ray in 1853.[38]Madison County, Alabama Record Center,

Bits and pieces of possible family history surfaced. Although relationships may not be apparent readily, most of the men identified had local connections. Though Joshua Barker and his wife were both from Virginia, he and Lucy Maria Mason married here in Huntsville in 1832. By 1850 they lived at home, with three children. No occupation was given at that time. Mr. Barker died in July of 1856, having been, it was said, a longtime resident of Huntsville. William Hunt in 1840 lived with the large family of William R. Hunt, who had served as jailer from 1833-1844.[39]Federal Census, 1850; MCRC; Federal Census 1850; Gandrud, Marriage'', 324, 475; Diane Robey, Dorothy Scott Johnson, John Rison Jones, Jr., Frances C. Roberts, ''Maple Hill Cemetery, Phase One'' (Huntsville: Huntsville-Madison County Historical Society, 1995), 17; Record, ''Dream, 170.

Other local men like James Cartright, William Hendricks, and George Cary visited the tavern only a few times. Edwin Glascock, Martin Doyle, James Crutcher, Alex Causby, Henry Glass, and William H. Fishback stopped in occasionally. Many of the men may have decided not to drop by Dunn's, headed for a different tavern, or simply went home.

P. A. Foote entered the tavern only once. Perhaps young Phillip was not accustomed to spending money on himself. His family members were early settlers, worthy ones, who had suffered great financial difficulties in previous years. His father, Phillip A. Foote, married Matilda Brown here in 1816. (The father's first cousin, Henry Foote, settled in Tuscumbia before moving to Mississippi. There Henry Foote entered politics and ran for governor of the state in 1851. He was elected and defeated Jefferson Davis in doing so.)

In addition to Huntsville the elder Foote, and his partner, John M. Taylor, had flourishing commercial business with offices in New York, Philadelphia, and New Orleans. Among other investments, Foote purchased three lots for over $3000 in the expected real estate boom at Triana in early 1818. However, the unforeseen drop in cotton prices forced Taylor and other partners, including Willis Pope, to suspend specie payments at the Planters' and Merchants' Bank in 1818. This and the depression of 1819 left Foote & Taylor unable to meet their many creditors. All their properties were put in the hands of trustees and sold; the contents of their merchant business, three town lots including Foote's "two-story frame house with its new brick kitchens and meat houses… framed stable and carriage house with enclosed garden." Phillip Foote, Sr., died in 1831 at the age of 38 leaving young children. Apparently any possible hard feelings between families were mended as young Phillip's sister Matilda married Alexander S. Pope in 1838, and a year later Mary Foote married his brother, Leroy Pope, Junior.[40]Dupree, Transforming'', 46, 50, 51; Gandrud, ''Marriage, 472; MCRC.

James L. Cooper was from a successful local family, and he soon became more successful at least in the eyes of many. In 1850 in Franklin County, Cooper married Mary Keziah Winston, sister-in-law to both Alabama governor Robert Lindsay and Mississippi governor John J. Pettus. She was also the sister of Alabama governor John A. Winston. The Coopers lived in Huntsville, and Mary is buried at Maple Hill Cemetery.[41]Robey, Maple Hill, 111.

Dr. Albert J. Russel came to the tavern at least six times, but he did not purchase a "drink." His father Lt. Albert Russel, Sr., had served in the Revolutionary War and located here afterwards on what became known as Russel Hill. Dr. Albert Russel purchased items as cakes, apples, snacks, cider, and cigars at the tavern. These healthy items did not help the good doctor; he died in July of 1844 at the age of forty-four.[42]Ibid, 14. Russel Hill is across from Butler High School on Holmes Street. A local D.A.R. chapter is named for the senior Russel.)

John P. Hawkins lived near Woodville. He had married Lucy Hodges in 1813; he married May Reedy in 1831. At his death in 1856, age about 66, he was noted as an old and respectable citizen who had served his country during several campaigns and always acquitted himself honorably and left testimonials to prove this fact.[43]MCRC; Gandrud, Marriage¸ 564

A lawyer by profession, William McCay, Jr., had married in 1825 the widow Mrs. Sarah O'Reilly. (She was a sister of General T. O. Collins.) Apparently McCay's father was an adventurous man. In 1837 word had been received in Huntsville of the senior McCay's death in Philadelphia as the result of severe wounds caused by an accident while traveling on the early railroad there. By 1850 both of the McCays were listed as schoolteachers with students boarding in their home.[44]Gandrud, Marriages'', 218, 264, 454, 321; Huntsville ''Democrat, March 18, 1843; 1850 Census.

The Patton family was very prominent in Huntsville life. The senior William Patton, born in Londonderry, Ireland, in 1779, arrived here with his Virginia-born wife in 1812 and proceeded to have a large family and a larger fortune. Anne Royall described Mr. Patton, who owned plantations and a partnership in the Bell Factory, as one of the richest men in the territory. Of his children, Dr. Charles Patton would purchase LeRoy Pope's fine mansion on the hill over looking town. His son, Robert Patton, would serve as governor of Alabama after the War. The elder William Patton died in 1846 and could have visited the tavern. If it were he who was noted in the ledger, perhaps he did not come more often because surely he had better wines and spirits at own his residence. It is probable that the guest at the tavern was the elder Patton's son, William M. Patton, who married Mary Ann Miller in 1831. Their years together in the early 1840s were particularly difficult. They lost at least four infant daughters and Mary Ann died in 1844, just a little over a month after the death of her last baby. William Patton, the younger, died in 1859 at the age of 52.[45]Robey, Maple Hill'', 2, 41; Anne Newport Royall, ''Letters, 122, 217.

Thomas Bibb may have still been flush with cash for his carpentry work on construction of the new Market House on the square while he spent time at the tavern.[46]Record, Dream, 94. One might recognize the Bibb surname. The Huntsville Bibbs were cousins of the two brothers who served as first and second governors of Alabama, who probably did not frequent Dunn's Tavern. Thomas, Robert and Benjamin Bibb did.

At least three Bibb brothers were early settlers and lived in and around Huntsville for many years. Although another brother, Benjamin Franklin Bibb, lived in Tennessee, he visited the tavern here often in 1843. Amanda, daughter of the brother William Bibb (not in the ledger), married first Mr. Bennett and then John J. Coleman. If the fourth brother, Reverend James Bibb, a Methodist minister, imbibed, he did not do so at Dunn's tavern. Thomas Jefferson Bibb, the carpenter, married Mariam Fielder and after her death married her sister, Elizabeth. He had done well and by 1860, at the age of 66, was worth $18,000. According to the family history, Tom Bibb came to visit his cousins and enlisted with Andrew Jackson. Bibb fought in the Battle of New Orleans, "captured a British Major who surrendered to him and whose sword is now in Washington." The history continues, "during the War between the States…General Sherman placed a permanent guard about the tomb of Thomas Bibb, because of his fine career at the Battle of New Orleans." This story has not been substantiated for either Thomas Bibb.[47]Gandrud, Marriage'', 117; Census 1860; Charles William Bibb, ''Bibb Family in America, (Baltimore, n. p. ,1941), 117- 119.

Nimrod Fielder, a carpenter by trade, came to Huntsville about 1824, and married Elizabeth Riggs. His many visits to Dunn's Tavern had not been too harmful to his health. Fielder died in 1854 at the age of 83 at the home of Thomas Bibb, fellow carpenter and his son-in-law. Nimrod "had an eventful life and was well known to all."[48]MCRC; Gandrud, Marriages, 539.

Perhaps his business was nearby or perhaps Henry Beal was just a thirsty man. His entry on the ledger was often the first one for the day, 29 visits in all. By trade a shoemaker, Mr. Beal later lost his wife, Eliza, in January of 1845, age 52 at her death. He remained at home with two daughters at least until 1850 when he was 50 when enumerated.[49]Gandrud, Marriages'', 483; Robey, ''Maple HiIl, 17.

Richard Green Hamlet enjoyed patronage at the Tavern; he was served 24 times according to the ledger. Called "Green" by his friends, in 1836 Green Hamlet was one among the company of men from Madison County who fought in the Texas War of Independence.[50]Gandrud, Marriages'', 484; Record, ''Dream¸ 87.

Only once did tavern-keeper Dunn list a surname preceded by a military title. However his title was clearly acknowledged when Col. Larkin Bradford's name was entered into the book. Larkin came from the family of a noted pioneer Indian fighter. His father, 1st Lt. Larkin Bradford, Sr., of the Tennessee Volunteers, had been killed fighting the Creek Indians at Talladega, Alabama "a tomahawk buried in his brain." Locally Colonel Bradford Larkin served as commander of the 63rd Regiment of the local militia.[51]Gandrud, Marriages, 338.

In Huntsville the Colonel had married Jane Catherine James in 1835. She died just a month after giving birth to their third son. Jane's tombstone reads she was "consort of Larkin Bradford who departed this life, June 6th, 1840 in peace, age 22 years, 'Lips I have kissed ye are faded and cold; hands I have pressed, you are covered with mould; form I have clasped thou art crumbling away; and soon in your bosom the weeper will lay.'"[52]Robey, Maple Hill, 11.

His three children now without a mother, Col. Bradford married the widow Louisa (Keyes) Thomas of Athens in September of 1843. Louisa Thomas previously had lost her husband, Micajah, one of the wealthiest men in Athens, in September of 1840. Louisa came from a distinguished family that included Revolutionary War veterans. Her father, John Wade Keyes, served at Bunker Hill, and this patriot named his twin sons George and Washington. Keyes then settled in Limestone County to raise his family. Surely Louisa adequately combined illustrious heritage and financial promise.[53]Robey, Maple Hill'', 7; Phillip Reyer, ''Limestone County, Alabama Marriage Book'', (Limestone, Ala. Hist. Soc., 1979), 9 ; Gandrud, ''Marriages, 338; Census 1850, 1860. It is always nice to marry for love, but it doesn't hurt to marry for love and money.

In May of 1844 Larkin and Louisa Bradford signed a note for over $981 to Joseph_B._Bradford, a very wealthy commission merchant of Huntsville. Joseph's wife Martha had been a Patton, and she was a sister to probably the wealthiest man in town, William Patton, already introduced. These were not people to be taken lightly or to have debts go unnoticed, even if they were family. (It is not clear what the relationship between the Bradford men might have been, but surely there was some connection.) When the note came due, court cases ensued before being decided at the State Supreme Court of Alabama. Unfortunately it was also revealed in the 1850 decision that Larkin Bradford was "utterly insolvent" and unable to pay the debt.[54]Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of Alabama, Vol. XVII, (Montgomery, AL, Power Press, 1850).

By 1850 Louisa and Larkin Bradford and their five children had moved to Lafayette County, Missouri, where his real estate in the census was valued at zero and his occupation as a tinner. By 1870 he was listed as a Tin-smith with four thousand dollars of real estate and five hundred dollars personal estate. Colonel Larkin Bradford, now no longer a man to frequent taverns, joined the Mormon Church and died about 1883 in Denver, Colorado.[55]Robey, Maple Hill, 11; < http://www.rootswebancestory.com/~tnsumner/bradfordfa.htm> (accessed March 2010.)

----

John Dunn's tavern, any tavern for that matter, was a place for men to enjoy politics. It was also a natural place for candidates to be seen seriously discussing the issues of the day with their-would-be electorate. William W. King wrote his friend, Governor Clay, "The bar seems to be the grand pacific into which all minor streams of liquor empty… it is the grand electioneering forum to which all characters, merchants, factors, sawyers, physicians & resort for the formation of friends and acquaintances."[56]William W. King to Clement C. Clay, February 28, 1836, Clay Collection, Perkins Library Special Collections from New Orleans ,

At least two of Dunn's regular customers that season were hopeful local politicians. The Huntsville Democrat announced candidates for Sheriff of the county, among others, Cortez D. Cavanaugh and George Carmichael. Tavern visits apparently were not detrimental to political candidates. George_W._Carmichael visited the tavern at least 19 times. On the other hand, the winner of that three-year term for sheriff was Cortez Cavanaugh who stopped in at least 42 times in the same six-month period. (The candidates probably also visited other taverns during this time.) However, in 1852 and again in 1859, the will of the people ruled and Mr. Carmichael became sheriff.

Cortez Douglas Kavanaugh, born about 1805 in Tennessee, came to Madison County and was soon accepted among the local sporting crowd. He married a suitable young widow Catherine (Connally) Lewis. Catherine's father was John O. Connally owner of the Green Bottom Inn and Racetrack, friend of Andrew Jackson, and raconteur about town. (Catherine had first married William Lewis, but he died in 1832.) After their marriage in 1834, Cortez was appointed administrator by right of marriage to the estate of Lewis along with her brother, George Connally.

Unfortunately Catherine's brother-in-law, John Blevins, another man noted for his racing stables, took a Lewis slave, Little Bill, without consent of the administrators. The slave later died in Mobile, and Kavanaugh threatened to prosecute in the name of the Lewis estate. Blevins, faced with the threat, replaced the dead slave with one named Jack, valued at even more money. However, in a suit eventually also carried to the Alabama Supreme Court by the four Lewis children, it was alleged that the bill of ownership for Jack, valued at $1680, was drawn in the name of Kavanaugh. Cortez Kavanaugh by then was insolvent and claimed Jack as his property. In 1847 his stepchildren sued for their shares of the Lewis estate. The case, originally decided in the Orphans Court under Judge C. C. Clay, Sr., was affirmed by the state court in 1849.[57]Reports argued and determined by the Supreme Court of Alabama, June Term, Vol. XVI, 817-827.

In the meanwhile Kavanaugh became an active politician, and of course his visits to Dunn's Tavern might be considered purely for campaigning. Kavanaugh was elected sheriff of Madison County from 1837-1840 and again from 1843-1846. In 1851-52 he was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives. Not reelected to that position, he served as postmaster in Huntsville from 1853-1857. By 1860 the census showed that Kavanaugh was now a family man; he had at least six children and one stepson in his household. His profession listed was that of Deputy Marshall. Interestingly, Mrs. Kavanaugh's personal worth was noted as $1200, perhaps the vestiges of her first husband's or her father John Connolly's estate. The family moved away from Madison County, and Cortez Kavanaugh died in May 1864 in Howard County, Missouri.[58]Digital Library on American Slavery, Petition #20184706, http://library.unc.ed/slavery/details.aspx?pid=3177.

The newspapers also listed those gentlemen who sought to represent Madison County in the next State Legislature. The Democratic candidates who stopped by Dunn's Tavern included Jason Jordan and Jeremiah Clemens. Jason Jordan stopped in at Dunn's only once; perhaps he visited other taverns instead. Although he and his wife, Charity Hobbs, shared long-time Huntsville connections, Jordan lost the election in 1843. Perhaps it was just as well. Jordan and his family moved to Holmes County, Mississippi where several of her family had already relocated, and by1860 his assets were valued at over $48,000. In the same year, Clemens and his wife were living with her father and Clemens had no monetary assessment.[59]Huntsville Democrat, July 6, 1843; MCRC; 1860 Census

Clearly the politician at Dunn's tavern with the highest aspirations was Jeremiah Clemens. At the time he was a young man of 29, already a lawyer and married to Mary, the daughter of wealthy merchant John Read. Like many southern men, Clemens volunteered as a private to fight against the Cherokees in 1834. He was elected to the State Legislature each year from 1839 to 1841. In 1842 he raised a company of riflemen and marched to fight in the Texas War of Independence. On his return to Huntsville, visits to the tavern did not hurt his chances with the all-male voters. He was reelected in 1843 and 1844 to the Legislature.

Later, during the War with Mexico in 1847, Jeremiah Clemens was a Lt. Colonel in the U. S. Army. He was next elected to the U. S. Senate from 1849-1853. During a short stint in Memphis as a newspaper editor, Clemens wrote two successful autobiographical novels about his experiences in Texas. Even though he was a known cooperationist, Clemens later represented Madison County at the Alabama Secession Convention. When the Civil War started, he accepted an appointment as Major General in the militia of Alabama but never saw active service. By 1862 he clearly recognized the hopelessness of the South's position and how devastating it would become. Clemens and others went to Washington in an attempt to see President Lincoln and initiate a treaty of peace. Despised as a traitor in the South, Clemens finally moved to Philadelphia where he wrote one of the first novels about the Civil War, Tobias Wilson. The book was published after his death in 1865.

In the first months, James T. Figures of Clarke County was a frequent visitor to the tavern. However his many purchases only included tobacco, coffee, cakes, cheese, apples and cider. Perhaps the young man was trying to socialize and make new friends. In his native Clarke County, his large family had centered on his parents Maj. Thomas Figures and Elizabeth (Walker) Coleman Figures. An esteemed citizen, the major had served in General Coffee's command during the Indian War of 1816. Young Figures came to Huntsville to serve as an apprentice in the newspaper business with his brother, William Bibb Figures. William Figures himself had come earlier as a novice to learn the newspaper business from John James Coleman, co-owner of the Southern Mercury. William Figures later purchased the newspaper and renamed it the Southern Advocate. After learning the trade, young James Figures returned home where he and another brother established the Grove Hill Herald in 1849. James Figures died in 1853 while tending patients of the Yellow Fever epidemic in Clarke County.[60]Gandrud, Marriages'', 536; Maria Bankhead Owen, ''Story of Alabama''. (NY: Lewis Historical Publ., 1949), 3: 145; John Simpson Graham, ''History of Clarke County, Alabama, (Birmingham, Birmingham Printing Co., 1991), 253, 57.

Also noted among Madison County citizens who occasionally stopped in at the tavern was John James Coleman. He was a lawyer and for a brief time owner of a local newspaper. His first wife, the widow Amanda Bennett, daughter of William and Sarah Bibb, had previously married William Bennett in 1828, but he died a year later. She then married John Coleman in 1841 and they had two children, Amanda Narcissa Graves Coleman and John Williams Walker Coleman. After her death in 1849, Coleman married as his second wife, Palmyra Jane, daughter of Samuel and Elizabeth Acklen. Palmyra Coleman died in 1860, "She is not dead but sleepth."[61]Gandrud, Marriages'', 363, 500, 523; Robey, ''Maple Hill, 11.

Again, noting the ties that often run so deeply in Madison County, Mr. Coleman, it seems, had well-regarded connections. John Williams Walker had married the daughter of LeRoy Pope and moved here from Petersburg, Georgia. Walker later became the first U.S. Senator from Alabama. In his letters John mentioned to his brother Samuel Walker his responsibility for their poor sister Polly, now widowed, nearly destitute, and unable to provide for her family. Apparently this is the same Elizabeth (Walker) Coleman who later married Tom Figures and relocated in Clarke County. John Coleman was likely one of her sons and thus a half-brother to the Figures men who came to learn the newspaper business here.[62]Bailey, Hugh C., John Williams Walker, (University, AL: Univ. of Al Press, 1964), 71, 171. (The two Coleman children were named perhaps for a Coleman relative, Narcissa, but also for Graves and John Williams Walker, two Walker brothers.)

The Gooches were another respected family. The father of the Gooch brothers, Roland Gooch, was originally from Albemarle County, Virginia and made the trip to purchase land on the first legal day of sales in February of 1818. He returned to Virginia and escorted his wife, Elizabeth and their five children to their new home in western Madison County. (Two of the Gooch sisters, America Virginia and Mary E. married Petty brothers in Madison County who decided later to try their luck in the gold fields of California. Mary died on board a boat on the Mississippi River and was buried in the river.) The third son, Capt. William M. Gooch, only stopped once at Dunn's Tavern. During this time he was probably courting Maria Combs before their marriage in 1844. William died of typhoid fever in October of 1861, age about 50. It was written "He leaves an interesting family."[63]Gandrud, Marriages'', 370, 480; ''Heritage of Madison County, 209-212; MCRC.

Brother, Nathaniel Matson Gooch, (called Matt), was born in 1822 after the family had moved to Madison County. Matt married first Susan Lightsey in 1850. Eight years later he married Mary Ann (Patton) widow of William Sellick. Mary Ann's brother, Dr. Charles Patton, at the time of the Civil War lived in LeRoy Pope's former house, Poplar Grove. Mary Ann Gooch, now widowed a second time lived in the cottage next-door that was destroyed by the Yankees as they fortified Patton's hill. Those homes were caught in a sketch at that time by an illustrator for Harper's Weekly''.[64]''Heritage'', 209-212; Gandrud, ''Marriages'', 506; ''Heritage'', 307. ''Harper's Weekly'', March 19, 1864, also seen on the cover of ''Incidents of the War: The Civil War Journal of Mary Jane Chadick.

One of the most frequent visitors, if not the most frequent, at Dunn's place was Cyrus Staymate, the tailor. According to the census he was not living here in 1840. By 1850 he was listed as single, born, c.1809, boarding with the Johnson family. In 1860 he was age 50, a tailor, single, with $200 personal value, and living in his own house. By 1870, age 59 he lived alone. There was no mention of Cyrus Staymate in local records after that.[65]Federal Censuses, 1840-1870.

Staymate's partner in business and at the tavern was William Higgins, also a tailor and also a bachelor. In the March 18th issue of the Huntsville Democrat for 1843 they announced to the public,

Having entered into co-partnership for the purpose of carrying on the Tailoring business in all the various branches….They hope by their constant attention to business, and the prompt manner that all work committed to their care shall be executed - to receive a liberal share of patronage.

The partnership was over at least by August of 1850 when Higgins, noted as "an old citizen of Huntsville," died.[66]Huntsville Democrat'', March 18, 1843; Gandrud, ''Marriages, 503.

----Dunn's Tavern was open approximately 146 days for the year 1843. Many of the regulars were already evident that second day of January 1843 when the account book began. However, 34 men made only one visit, 19 came only twice and 16 came three times. Clearly it was the regulars who kept the tavern running. On a particularly good day $4.61½ to $5.09¼ might have been extended on credit. On most days tabs ran about $2 to $3, and on a poor day the amount was as little as 25 cents. Although Henry Beal was often the first entry of the day, clearly the tailors William Higgins and Cyrus Staymate were the steadiest (or unsteadiest) customers during this brief period. Henry Beal's 29 visits pale in comparison to 42 stops by Cortez Cavanaugh, Crusaw Robinson's 43, Cyrus Staymate's 75, topped only by his partner William Higgins at 80 visits. Dunn had apparently hired R. S. Mitchell to work around the place in June as Mitchell received cash out according to the ledger. Yet again, one can only surmise the amount of money and the number of customers who paid John Dunn in cash.

The reader will probably never learn more about John J. Dunn - ever. The last pages of the daybook show a deterioration of the handwriting of the entries; the pages of the ledger show even different handwritings. Was Mr. Dunn showing signs of age, a stroke, illness, too much alcohol himself, or simply dim candlelight? Nevertheless it is clear that something is amiss. Some days the tavern book had no entries, and attendance slimmed down to a few customers. By June 1843 the handwriting and the accounts have become difficult to decipher. The dates became confused and muddled, the handwriting more than a little shaky. The last entry on June 29 was to one R. S. Mitchell for cash out, $1.00. The last two customers served were those old partners, Cyrus Staymate and William Higgins, fixtures at the tavern. Mitchell would have to look for new work; Staymate and Higgins would have to look for a new watering hole.

Footnotes